The Silencing of the Native American

Stop telling us to “Get over it.” Native Americans are more than football mascots. We are human beings.

Like many young adults in the United States, social media interaction has become a permanent fixture in my every day life. From Facebook to Reddit, I can’t resist the urge in participate in a rousing discussion about topics that range from adorable cat videos to more serious content involving political and social issues. But while the internet can be my best friend in the whole wide world, it can also be my fiercest foe.

Growing up, I was taught that words were just words and the best way to respond to such negativity was to brush them off. But how are you supposed to respond when the words used against you have a deep history that is drenched in hundreds of years of atrocious pain, bloodshed, and unspeakable inhumane actions? When those words are meant to attack not only you but are an attempt to silence an entire culture, it becomes something much deeper and exposes a darker mindset that’s still ingrained in our society.

As a Shoshone-Gabrielino Native American, I try to keep up with Native American publications on Facebook to read today’s headlines regarding Native American issues and topics. The Internet has provided an amazing tool to unify those of Native descent and non-native supporters and has contributed to making the Native voice louder than it has ever been before. Native American people and their concerns are reaching the masses in ways we didn’t think were possible. We are finally making national headlines regarding different issues like tribal opposition to the XL Pipeline, environmental issues (one of the oldest and important priorities in the heart of the culture), preservation of sacred sites, and of course, the controversy over the usage of the slur “Redskin.”

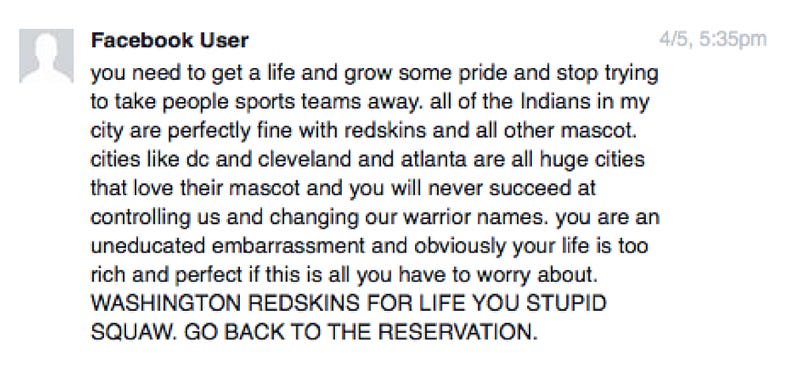

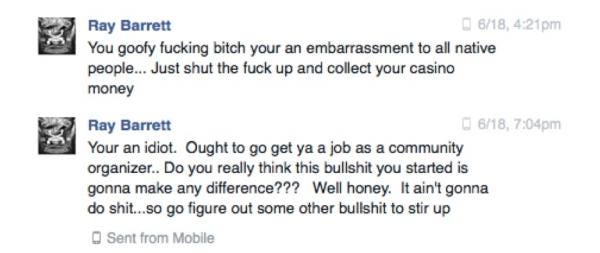

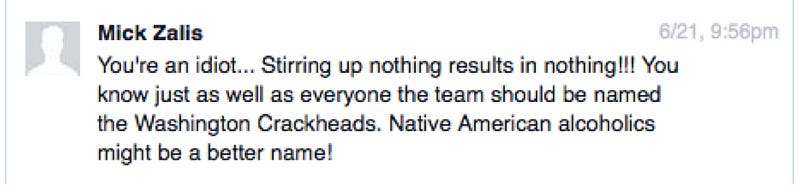

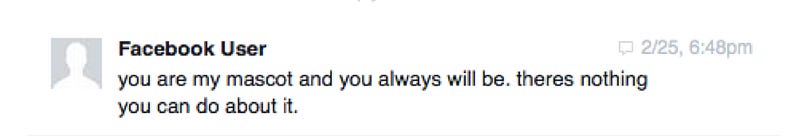

But ignorance also refuses to remain silent. It will seize every opportunity to make its ugly voice heard loud and clear. This same voice recently came screaming to Navajo native activist Amanda Blackhorse, known for her fight for the change of the name of the Washington Redskins as the lead plaintiff of Blackhorse v. Pro-Football, Inc. In her recent contribution to the Indian County Today Media Network website, Blackhorse posted a few of the many hate messages she has received from the supporters of the Washington football team’s use of the name.

Unfortunately, these words are part of a long-standing resistance to the indigenous people of the United States in an effort to silence the Native American voice. The oppression of the indigenous peoples of this land is nothing new.

Ever since European feet hit the already-occupied soils of the land, the assimilation and cultural (and mostly physical) annihilation of Native American people finds itself not only part of American history that people want to forget but also the ongoing cultural identity war that they willingly choose to ignore.

One would think with the advancements we have made in education and research regarding our history, there would be more respect for the indigenous people who tended the lands and made enormous contributions to the history and building of this country and the Americas in general. But once again, the Native American voice is symbolically being put back on reservations by those in office and the public.

The most common theme we see among negative comments responding to Native issues is that “the past is the past. Get over it.” This implies that Native American issues have been resolved or just don’t exist today and there is no need to address them.

The hard reality is that Native American tribes face many hardships, displacement, and discrimination to this very day. The racism towards Native American groups is still rampant and attacks the very few things we have left that make us who we are. The silencing of the Native American is not only a result of our activism, but also of our identity. The belief that the Native American is just a figure of the past and whose culture was taken under the so-called manifest destiny of the European settlers, still holds water in a lot of people’s minds, therefore making the concerns of indigenous people non-existent and unnecessary.

Dr. Frances Borella, an anthropology professor and adviser of the Native American Inter-tribal Student Alliance at Mt. San Antonio College in Walnut, Calif., said she believes that people don’t realize how many Native people are still here today. According to her sabbatical research on issues affecting Native American students, she found that the biggest issues among them was the feeling of invisibility in the eyes of modern society and lack of empathy and care regarding their concerns.

“[They] are dismissing the Native people as real people that should be respected and should have the rights to be living how they want to live and not be subjected to the racism and discrimination,” Borella said. “We are suppose to be a multi-cultural nation that thrives on distinct groups. We are suppose to maintain those things and have all that but yet, Native people still judge that way or dismissed and act like they don’t exist. To me, that’s the bigger issue.”

Borella said one of the biggest reasons why some people, especially those holding political positions, are quick to silence Native American voices is due to what is called “environmental racism.”

“A lot of the resources on this planet we need, the ones left in the United States, are left on Native American reservations. So they are trying to get their hands on the last bit of resources in the United States and because of that, they are pulling out everything they can to get at those resources. They are picking on those particular groups without concern about the environmental cost because they figure ‘Oh, they are just Indians. They can live in the pollution.’ It’s really bad right now. There’s a lot of that going on.” -Dr. Frances Borella

As Native American issues are finally making news headlines, so is the rise of the myth that the activism behind Native American issues, such as the now famous Washington Redskins controversy, is something recent and new. While there has been a newfound spotlight on indigenous issues, there is nothing new about the fight and activism from indigenous groups. Native American activism, such as the fight to change the Washington football team’s name, has been going on for many generations. But with such limited outlets of media before the creation of internet and social media, the Native American movement and its concerns were practically ignored in its early manifestation. Not only did the creation of the Internet and social media finally bring a face and a voice to Native American people, it also brought them power.

“In the past, we didn’t have power,” Borella said “But now we can have economic power, political power, and a voice on things like the internet. Because of that, we are stepping away from being pushed around and they don’t like that. They don’t want that because the reality is there is guilt about what happened and so the indigenous people have rights and they were screwed over so bad. People just don’t want to confront that. They would just shut you up.”

From the introduction of the European concept of blood quantum (which is the percentage of a person’s ancestry in determining how “Native” one is) to the campaigning of the idea that the Native American is something of the past, the tools of assimilation are still being used to diminish the culture’s identity. This is also seen in claims that anyone born in the United States is a “Native American” in an attempt to downplay Native concerns, completely ignoring the rich indigenous history of the country. Borella said that by diluting “Nativeness,” it can be used to silence Native Americans by claiming they are none of them left.

“The whole idea is to try to dilute the Native American out by defining who you are on their terms and not yours and saying there aren’t real Natives left,” Borella said.

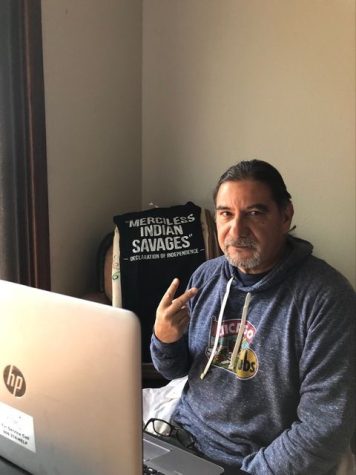

Tony Wilson, an enrolled member of the Eastern Band Cherokee Nation, said he faces obstacles in making his voice heard because he is of mixed blood and that type of questioning.

“Being Native is not about blood quantum as much as it about being about who your family is and where you were brought up. So all that stuff is a big distraction,” Wilson said.

Wilson said this is assimilation. “They say if we want to be in the modern world, we just need to get over it and the term redskin should offend not any Indian because it’s a badge of honor. No, it’s not. It’s assimilation. It’s making you less than. So people need to understand that and people need to immerse themselves back into their own community and their own culture.”

Not only are we seeing opposition from non-natives, we are also seeing criticism and negativity from within the community as well. People from both native and non-native blood have been criticizing the activism of image-centered activism, such as the call for the Washington football name change, as a distraction from bigger issues such as the rise of suicides and alcoholism among Native Americans and extreme poverty on reservations. Wilson said that minimizing any issues going on in the Native world is the ultimate tool of assimilation.

“I’ve heard my sister say this, who is full-blood by the way, ‘It’s been 200 years since we’ve walked. Get over it.’ It’s like, how can you say that? But it’s the tool of assimilation, a distraction, something bright and shiny. We got more important things to worry about? No man, you don’t. There’s nothing more important to worry about than the survival of your culture. Your community, your family values. That’s what people don’t understand when they talk about being Native.”

While the fight for the Redskin name change may seem minor to the more threatening issues that are happening within our culture, many Natives see the fight for a name change as a catalyst for the exposure of bigger issues, since those issues are not getting media attention despite the urgency for awareness. For Borella, the first step in tackling those bigger issues is for the public to take the Native American seriously and not just as a mascot for a sports team.

“I think before we can tackle the big issues, we must have respect,” Borella said. “We can’t get respect when people do not see us as human beings. The whole Washington Redskin issue deals with not seeing Native people as human beings but as items to be mascots. When they see us as human beings, then we can deal with the bigger issues.”

Despite the negativity and attempts of downplaying indigenous issues, the Native voice pushes on to become even louder and garner support from people from all walks of life. The continuous shredding of the image of the stereotypical silent-but-stoic historical figure that is deep rooted in a common perception of the Native American persists thanks to crucial tools such as the internet and social media.

Borella said that the major key to the making the Native voice grow stronger is through education, and with the Internet and social media, Native Americans can finally put a face to that voice by showing the culture does in fact exist. By showing Native Americans in contemporary situations such as being involved in music, sports, politics, and activism, people can see that Natives are humans too and deserve the same respect. As for the negativity, Borella said we have to keep pushing on.

“Education is key so it’s important that we continue to educate people about Native issues appropriately and get the real messages out there. I think there is always going to negative stuff and trolls, and people who like causing trouble. They are going to be out there just to make you feel bad regardless if you’re Native or not. So, you just have to focus on the positive.”

Substance is a publication of the Mt. San Antonio College Journalism Program. The program recently moved its newsroom over to Medium as part of a one-year experiment. Read about it here.