Learning to Swallow

Accepting the taste of feminism

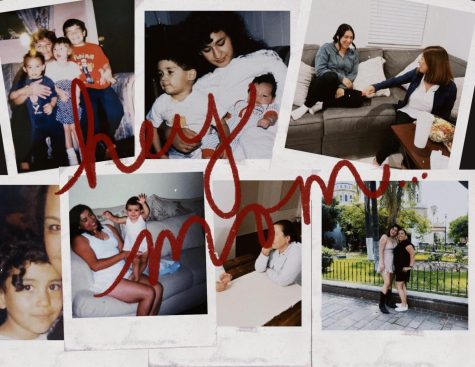

The room was uncomfortably cold. The fluorescent lights glared against the dingy, speckled linoleum floors of the inner waiting room. A dozen gowned women sat slouched in padded chairs that lined the whitewashed walls, arms crossed to preserve warmth. At first, they were silent. The only sound was the dull, almost inaudible, ticking of the clock.

Tick-tick-tick. It mocked their hunger.

They hadn’t eaten or drank anything for nine hours, and they were starting to get restless. Some began to hunch over clutching their midsections, others tilted their heads back to rest against the wall in attempt to sleep, while others just stared at the floor.

Each time the metal door squealed open, the women shot their eyes up in hopeful anticipation. And each time a new woman was escorted in, sighs of disappointment filled the space. They were waiting for the woman with the clipboard. She was the way out.

“I’m gonna have pancakes when I’m out of here,” one woman in the corner whispered to her slumped over neighbor. The other woman cocked her head slightly and forced out a grin.

“I’m fucking starving,” another woman said.

The standoff with silence was broken by a group of women in their twenties and thirties sitting in a corner who raved about the savory meals they would later consume. They cackled in delight as the descriptions became more elaborate.

The conversation evolved into their present circumstances.

“I have four kids and I just can’t handle any more,” one woman explained. Her companions groaned in solidarity.

“This is my third one,” another said almost laughing.

The conversation and cavalier justifications continued for over an hour. Surely, no woman wanted to be there, but the unanticipated happened, and there they were, joking and laughing as though it were an ordinary encounter.

Then, the woman with the clipboard entered the room. She wore plain green scrubs that fit snugly against her stout figure. Her grey-streaked, copper hair was twisted into a bun at crown of her head. She peered down at her clipboard, snaking her index finger down the page. After a few moments of collective bated breaths from the waiting women, she called out a name.

Recognizing her name, a young woman — still just a teen — slightly perched up in her chair, momentarily locked eyes with the clipboard woman, then diverted her eyes away. As she pushed herself up out of the chair, she tucked a chunk of her thick, dark hair behind her ear. The heels of her feet lightly scraped the floor as she shuffled toward the door.

“Good morning,” the clipboard woman — a medical assistant — said with a reassuring smile. She pushed the door open wider to allow the girl to walk through. The door slammed closed behind them. The medical assistant gently placed her hand on the middle of the girl’s back as she guided her down the hall to an examination room. This room was even colder.

Another woman, the sonogram technician, was waiting in the exam room. She sat in a metal rolling stool between the exam table and a sonogram machine.

“Take a seat on the table,” she said.

The protective tissue crunched and ripped as the girl climbed onto the table and laid back. She placed her arms rigidly at her sides, clenching the fabric of her faded blue gown and fixed her gaze on the overhead light that beamed down on them.

As the sonogram technician lifted her gown, the girl closed her eyes, flinching as the frigid gel hit the skin of her lower abdomen. The tech moved the sonogram probe in small circular motions around the girl’s stomach. “You’re about two to three weeks,” the tech said. “Do you want to see?”

“Not really,” the girl replied opening her eyes anyway. She looked at the monitor and gently nodded her head. It was a small, shapeless mass. She returned her gaze overhead. “Okay,” she said holding her breath. Her eyes stung with tears.

The tech set the probe down and rested her hand on the girl’s ankle. “Are you sure you want to do this?” she said leaning in closer.

“Mm-hmm,” the girl replied as she let out her breath.

The tech wiped off the gel and gently pulled the girl’s gown back down to her knees. She then explained the process of the procedure. “They are going to put you under with anesthesia and use a machine to scrape the inside of your uterus,” she said. “This will cause you to miscarry. You may have mild cramps and bleed for a few days after, but that’s normal. The procedure should only take a few minutes.”

The girl nodded still staring into the light.

“Do you have any questions?” the tech asked.

She shook her head back and forth.

The tech guided the girl into another room where she would be prepped for surgery. She woke up to a petite, blonde nurse standing over her, explaining that the procedure was over. It had all happened so quickly.

The anesthesia left her disoriented and groggy, so the nurse helped carry her out to her ride home. The nurse wrapped one of her arms around the girl’s waist and clutched the girl’s wrist that was propped around her shoulder with the other. “This must be what it’s like to be drunk,” the girl quipped to the nurse. “I’ve never been drunk.”

After the procedure, the girl went home and slept for the rest of the weekend. There were no pancakes or indulgent meals; just sleep, stomach pains and intermittent tears.

Perhaps the decision to terminate her pregnancy was that of selfish consideration, but it was a choice riddled with guilt and shame. Nevertheless, it was a choice she feels fortunate she had.

The girl is one of hundreds of thousands of women each year who terminate their pregnancies in the U.S. In 2011 alone, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention recorded over 730,000 legal induced abortions, a figure which has been in steady decline since 1990. The cause of the decline has been attributed to a number of factors, including easier access to birth control and emergency contraception like Plan B. However, the future of women’s reproductive rights are in jeopardy.

The 2014 Supreme Court ruling that exempted some religious, family-owned companies from the birth control provision of the Affordable Care Act set a precedent about women’s rights over their bodies, leaving it in the hands of employers and politicians. And birth control is merely the beginning. The contention over abortion has been resurrected by Republican presidential hopefuls who have promised to overturn Roe v. Wade and outlaw abortion — some even opposing exceptions in the case of rape, incest or threat to the mother’s life. If a Republican candidate takes the office in 2017, women may no longer have that choice.

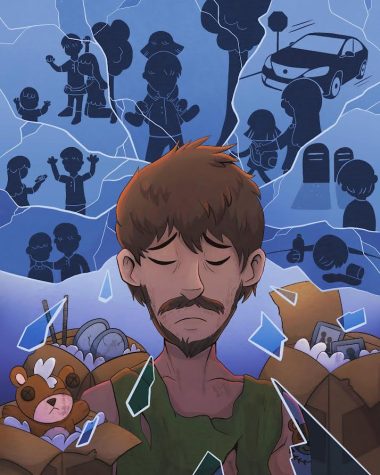

However, the idea of choice transcends reproductive rights. Rather, choice is a manifestation of liberty. Rights beget choices and choices beget control. Mitigating women’s rights narrows choices available to them, and therefore limits their control over their lives.

As with reproductive rights, women’s rights are not guaranteed. Rather, they are the direct result of lifetimes of dedication and embattlement against oppression. These battles have been won little by little for over a century and a half, and perhaps even earlier. Today, women can vote, attend college, buy property, pursue any career, hold public office, and so on — rights women didn’t always possess; rights earned off the backs of feminists. And yet, many are content with these most basic of human rights. Moreover, many women — and men — have shed responsibility to improve the status quo for women as well as future generations.

The argument that women have achieved equality is simply false; there is much left to do. To date, women earn only 79 cents per dollar that men earn, which will take more than a century to equalize. The wage gap is even worse for women of color. Additionally, women only hold one-fifth of Congressional seats (104 of 535) with only three serving as committee leaders now that Republicans have taken over Capital Hill. In business, women occupy a mere six percent of leadership roles like chairman, president, CEO, and CFO in Fortune 500 companies.

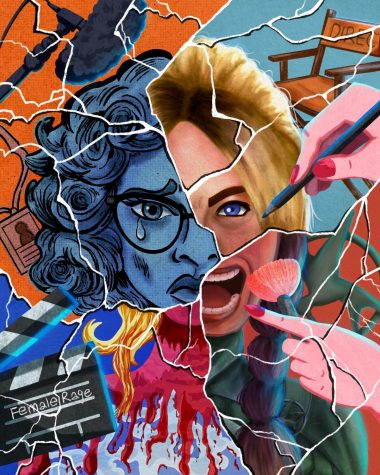

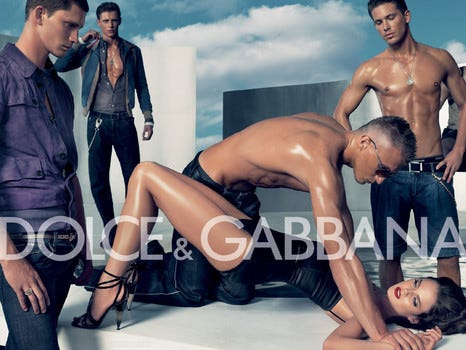

Women’s role in media remains cheapened by objectification and over-sexualization. Women are three times more likely to be dressed sexually than men as well as depicted in a violently-suggestive manner. This persistent sexualization not only demeans healthy sexuality for men and women alike, but it also distorts perceptions of beauty and cripples self-image for women and young girls.

Despite how far women have come, they still lack a myriad of rights and privileges deserved by all people. Moreover, feminists must work to change long-held, negative mentalities about women, beauty, and sex.

Beyond a lack of awareness about the inequities of women, the fundamental issue impeding the feminist movement is the aversion of the label itself.

The word “feminist” is too bitter for people to tolerate. Many have vigorously denied association with feminism while in the same breath affirming that they believe in equal rights for men and women.

Even celebrities regarded as strong female figures have side-stepped the term. Katy Perry, Demi Moore, Carrie Underwood, Madonna, Kelly Clarkson, Kaley Cuoco, Susan Sarandon, and Sarah Jessica Parker have all publically denied being a feminist; some preferring the term “humanist.” The public rejection of feminism by these Hollywood elites has only exacerbated the erroneous and negative connotation of feminism.

Humanism, however, falls short in its ability to level the playing field. It simply does not meet the needs of women or any single group enduring discrimination. The problem with the term humanist is twofold. Firstly, the definition itself is in conflict. One source defines humanism as “a system of values and beliefs that is based on the idea that people are basically good and that problems can be solved using reason instead of religion” while another defines it as “any system or mode of thought or action in which human interests, values, and dignity predominate.” According to the American Humanist Society, humanism is “a progressive lifestance that, without supernaturalism, affirms our ability and responsibility to lead meaningful, ethical lives capable of adding to the greater good of humanity.”

Conversely, the definition of feminism is clear and constant. It is the belief in the social, political, and economic equality of the sexes.

Secondly, humanism ignores the reality of gender-specific inequality. Its focus on everyone means its focus is on no one. Feminism concentrates on overcoming systems of oppression where women are the victims. However, it does not allege that women’s rights overshadow the needs of other oppressed groups. In fact, feminists have historically supported the advancement of other marginalized peoples.

The concept of feminism is simple, but the perception is polluted. Feminism has routinely been villainized as the enemy of traditional values. It has been characterized as a faction of indignant women who wish to systematically eradicate the world of men, despite the fact that feminists have also combated the inequities of men. However, the effectiveness of these perpetuated stereotypes has created a divide between the belief system and association with the title.

Regardless of the collective mentality about feminism, it remains rooted in equality, while at the same time, is unique to the individual. Some feminists affirm that activism is a tacit requirement while others believe it is simply a mindset. This embodies the flexibility of feminism — one does not have to subscribe to every facet advocated by the movement to be considered a feminist.

Truly, the feminist ideology focuses on the provision of choice. The fight for equality has been based in giving women the power to choose the trajectory of their lives.

That means having the choice to work or be a stay at home mother; the choice to vote or be inactive in politics; the choice to be a parent or terminate a pregnancy.

The realization of true equality for women rests on the unity of proclaimed feminists and those — both men and women — who can’t stand the taste of the word to come together to protect the liberty of women. Without choice, the fate of women’s lives are in the hands of people who believe they know the needs of women better than women do.

Jessica Cardenas Fuller is a transfer student of the Mt. SAC journalism program where she served as managing editor of the newspaper and editor-in-chief of the magazine. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree from Cal State Fullerton and is currently working on a master’s degree in education and serves as a faculty assistant and project coordinator for the adviser of student media at Mt. SAC.

This story is a part of a special alumni series. Students who have graduated or transferred from Mt. San Antonio’s journalism program are featured weekly on Fridays.