You Fucking Matter!!!

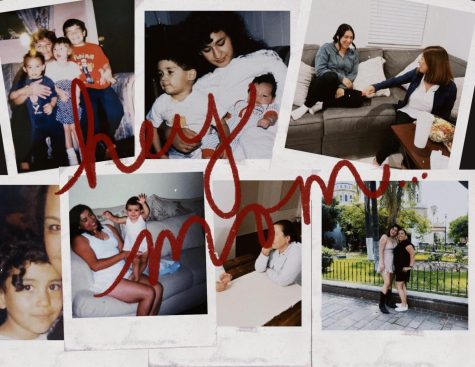

A personal recount of depression, attempted suicide, and ECT

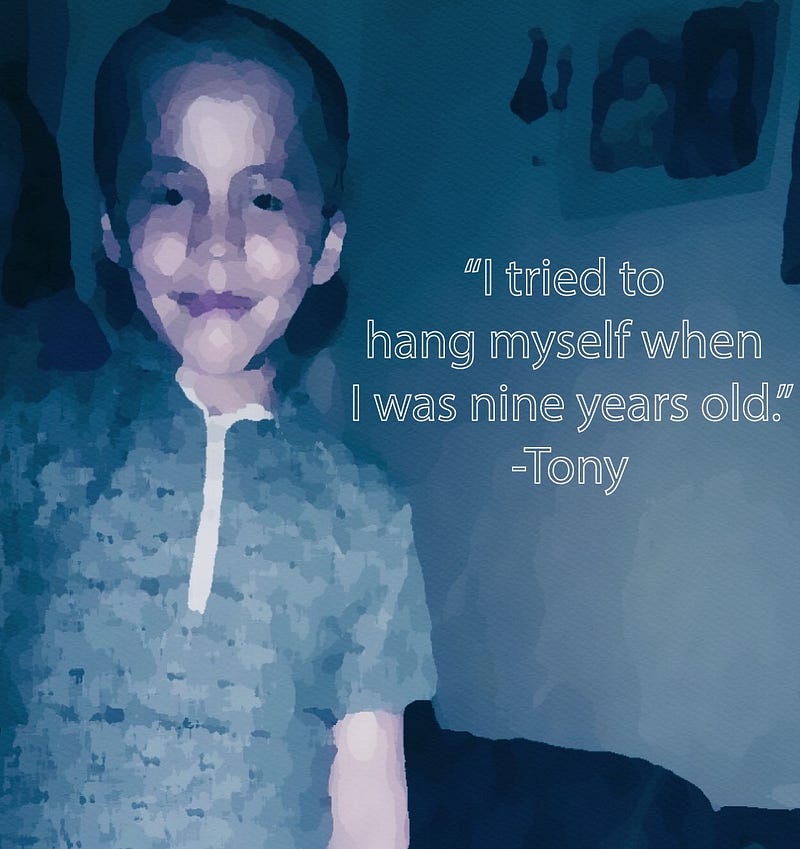

Beneath the spring leaves, Tony climbed an old oak tree in his backyard, carrying with him a clothesline he had detached from two old-fashioned T-shaped poles, which usually held four rows of fresh laundry. He tied the clothesline around a branch, climbed down from the tree, and stood on top of a milk crate his father had brought home from work. Atop the milk crate, he tied the other end of the clothesline around his neck, kicked the crate, and proceeded to fall on his ass, thwarting his first suicide attempt. Tony was nine years old.

There were clear marks and friction burns on his neck from where the rope had burned his skin as he fell, but the fall wasn’t the only pain he’d feel that day. He soon noticed his mother, who had been on her way out of the house to hang laundry, staring at him on the ground: “My mom saw me. She had seen what I tried to do … she was in shock.”

Once his mother recovered from shock, she grabbed a belt and spanked him: “I felt so bad after that — so ashamed — that I didn’t try it again until I was thirteen.”

On the ground with grass beneath his aching backside, Tony realized that his plan hadn’t worked, but what he hadn’t known at the time was that there are so many others like him, that each day, an average of over 5,400 young people grades 7–12 attempt similar plans of their own, and that suicide is the second leading cause of death for ages 10–24.

Tony’s continued struggle with depression and suicidal ideations first began after his brain surgery. At nine years old, he had already undergone brain surgery to remove two subdural hematomas — blood clots — the size of golf balls that had been pressing down on his brain. The resulting surgery left him with missing brain tissue, which he believes caused his symptoms of mental illness.

At 13, he once again tried to end his life, using a different method. On his way to school one day, he drank a hand-concocted mix of chemicals and pills. He became extremely ill 15 minutes after his arrival, and was taken to the hospital where he stayed for roughly a month to receive continued treatment. His hospital stay at 13 marked the beginning of a long journey to find the right combination of treatments to relieve his symptoms.

In the hospital, Tony was assigned a psychiatrist that “could read him like a book,” and was diagnosed with manic-depression, an older term for what is known as bipolar disorder today.

According to WebMD, bipolar disorder is a form of mood disorder, defined by manic or hypomanic episodes, changes from one’s normal mood, accompanied by high energy states. Being “manic” often involves sleeplessness, hallucinations, psychosis, grandiose delusions, or paranoid rage.

Depressive episodes can be more devastating and harder to treat than in people who never have manias or hypomanias. Those who are severely depressed also might need hospitalization to keep them from acting on suicidal thoughts or psychotic symptoms, such as delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized thinking.

In addition to intensive therapy, Tony was prescribed tricyclic antidepressants and lithium pills to manage his mood disorder symptoms, which had worsened by age 13 due to the pressure of being bullied at school.

“I had moved to a new school, and it was just the fact that I was always getting beat up on [that I was so depressed]. I was a really scrawny kid.”

The experience of being bullied was so traumatic for Tony that he continued to have nightmares of being chased by his adolescent bully long after his suicide attempt at thirteen.

“I had the nightmares well into my 20s. It was just me; trying to run from him. I called [the bully] ‘Gator.’ He was the kind of kid that would steal your baseball, scratch your name out of it, write his name, and say it was his — Stupid shit like that. He represented some kind of real, dark force that made me feel incredibly helpless.”

According to a 2010 study on involvement in bullying and depression in middle adolescence, being bullied may be a traumatizing event that results in depression, and is linked to psychosomatic complaints, low self-esteem, symptoms of depression and anxiety, and suicidal ideations, as well as suicide attempts; depression in youth also predicts experiences of both becoming a victim and of being left alone against one’s wishes, as a result of distorting one’s self-image — thereby impacting the development and experience of adolescent social interactions.

Since age 13 until his current age of 47, Tony has continued to see a therapist and to take medication in order to cope with his symptoms of depression, mania, and any anxiety during social interactions. The only exception was a five or six-year period that he calls “the worst years of [his] life,” during which he didn’t see a therapist, nor did he take medication regularly. However, the combination of medication and traditional psychotherapy hasn’t been enough to provide Tony with the level of escape and relief from his symptoms that he desired. His continued desire for relief led him to a dangerous and controversial medical treatment that resulted in worsened symptoms and lower self-esteem.

“When you’re suicidal, you’ll do anything for relief.”

Desperate for relief, during one of many depressive peaks in his life, Tony chose to undergo a procedure he knew could result in permanent brain damage — and subconsciously hoped would kill him.

“They took me in a cab to the hospital, to somewhere were they did ECT. I remember being wheeled in by an assistant, strapped down, and given a mouthpiece so that I didn’t bite my tongue off. Then I remember the headaches — like getting kicked in the head. The thing I remembered the most was forgetting my own name. When people called out, ‘Tony, Tony, Tony!,’ I thought they were talking to someone else.”

ECT, or Electric Convulsive Therapy, is a procedure done under general anesthesia, in which small electric currents are passed through the brain, intentionally triggering a brief seizure, with the goal of changing the brain’s chemistry in order to relieve the symptoms of certain mental illnesses. It has been known to cause both short-term and permanent brain damage, loss of memory or motor skills, and has left many who seek relief experiencing worsened symptoms of mental illness, and complete relapse after initial success.

According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information and the U.S. National Library of Medicine, ECT is helpful for 52.2 percent of patients; however, the relapse rate is up to 100 percent even after successful electroconvulsive therapy.

“When I sought out ECT, it was sold as a kind of fail-safe; like if nothing worked before, then this would.”

Despite the risks, for those experiencing major depression and suicidal ideations, the narrow sliver of hope for relief by ECT often temporarily outweighs the rationale of avoiding the risks of permanent brain damage.

For Tony, ECT worsened his condition to the point of complete debilitation. He couldn’t work. He couldn’t think clearly. Temporarily, he couldn’t remember his own name: “It’s like being a baby. You have to learn everything all over again.”

The impact on his self-esteem continued to impact his social interactions. Post procedure, after regaining some of the cognitive abilities that he had lost, Tony battled increased feelings of worthlessness and guilt. He had felt naive for the part of him who believed the procedure could work, guilty for the part of him who had hoped it would kill him, and felt like a burden to family who supported him as a result of his condition degrading to the point of disability.

Tony had undergone ECT with the mindset that he had nothing to lose — a dangerous frame of mind which leads many others to undergo the procedure as well. According to Mental Health America, ECT is administered to an estimated 100,000 individuals per year.

“After 60 years of use, ECT is still the most controversial psychiatric treatment.”

The primary reason that ECT remains controversial is because of the disparity between researchers and the methodological inconsistencies in available research. Some conclude ECT to be a “quick and easy solution” compared to long-term psychotherapy or hospitalization; while other researchers emphasize caution over the side effects and express concern for long-term consequences — recommending that, despite the “recent increase in ECT,” it only be used as a last resort.

After experiencing such physical, mental, and emotional decline, Tony believes ECT should not be used under any circumstance and should be illegal: “If there was a congressional hearing for all of the psychiatrists that did ECT, nothing would scare them more than that — then, they’d finally stop doing it.”

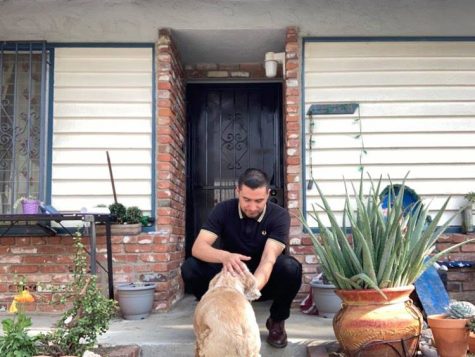

During his continued struggle, at a point in his life where he couldn’t imagine things getting better, Tony found a resource he had never heard of before that finally gave him the relief and drive that helps him better manage his symptoms today — a resource in which he found a sense of belonging among a group of people who understand him, who have had similar experiences; a safe place where he isn’t bullied, has many friends, and discovered his ability to help others.

Around the time of one of his last suicide attempts, Tony learned about DBSA, Depression Bipolar Support Alliance, a peer run support group; which according to their group introduction means, everyone in the group has “been there, is there, or knows someone who is” experiencing symptoms and hardships related to depression or bipolar disorder.

Upon first learning of DBSA years ago, Tony was skeptical of any other helpful resources or treatment practices and resisted attendance: “My therapist told me about DBSA. I had to go kicking and screaming. I had to go because my therapist said she’d stop seeing me if I didn’t go.”

Despite initially resisting attending the DBSA group, Tony liked the experience, and continued to attend its meetings, which marked a turning point in his search for relief. Being in an environment where he was able to hear similar stories of hardship, of others struggling with the same problems that he had, proved beneficial to his outlook. Tony became a group regular, started leading group discussions as a facilitator, and decided to start his own chapter of DBSA to foster an environment of equality and support.

“So I walked in, there was like a circle of chairs. It looked like your standard group meeting. There was feedback, a dialogue, so there was an actual point to it. Then I got to see that people had been there. They could actually relate, and it was surprising — I didn’t have to explain myself. It was cool because suddenly I had people visiting me that weren’t friends or family. It felt good.”

Feeling like one of them, that sense of belonging and being understood, and that break from the social stigma of mental illness was the relief missing from the other methods of treatment that Tony had tried. Medicine and pills address the chemical side; therapists evaluate the patient’s coping skills and introspective progress on a one to one social interaction; DBSA provides a community.

For Tony, DBSA is a lifesaver: “I hear that a lot. I’ve seen it. In fact, I’ve had to intervene, take people to the hospital, go through their [suicide] attempts.”

“You know the scary thing is, they would be dead if they were alone. We’re talking some serious overdoses. If they didn’t have anyone to reach out to, no family or friends, then they’d be dead. It sounds a little dramatic, but it’s true. DBSA saves lives. I know. It saved mine. Because if people are suicidal, if they have nowhere to go, that’s a place where they can go.”

Beyond pills or ECT, Tony explains what he really needed while experiencing the lows of depression and suicidal ideations:

“When I’m in that depressive state, sometimes I just really want someone to grab me — shake me — and tell me, ‘You fucking matter, man. You fucking matter!’”

Finding the right combination of medication and therapy has kept Tony alive. Finding a community of people who remind him that he matters through DBSA, however, gave him reason to live. Even during the times when his depression makes it difficult to feel anything beyond an overwhelming feeling of worthlessness, Tony now has something to hope for. A hope that he now gives to others, who like him, matter and simply needed someone else to say so.