Sex: An Alternative to Suicide

A personal recounting of clinical depression, attempted suicide, and sex as a source of relief

After giving his first partner “head” through a grocery bag used to hold fruit, James realized at 13 that sex, with all of its “awkward” pleasures, was a great distraction from the haunting fog of clinical depression that has plagued him for as long as he can remember.

“When I was a little kid,” James explained, “I would retreat into a fantasy world and use my imagination to take myself away, escape. When I got older,” he paused, “I did anything and everything for relief, but mostly, I just had a lot of sex.”

According to an article on Hypersexual Disorders, sex addicts crave sex for the euphoric pleasure. Like the high of drugs, sex provides them an endorphin induced high, and rather than being about intimacy sex becomes an escape from painful or unpleasant emotions and a solution to stress — in other words, sex is a means of self-medicating.

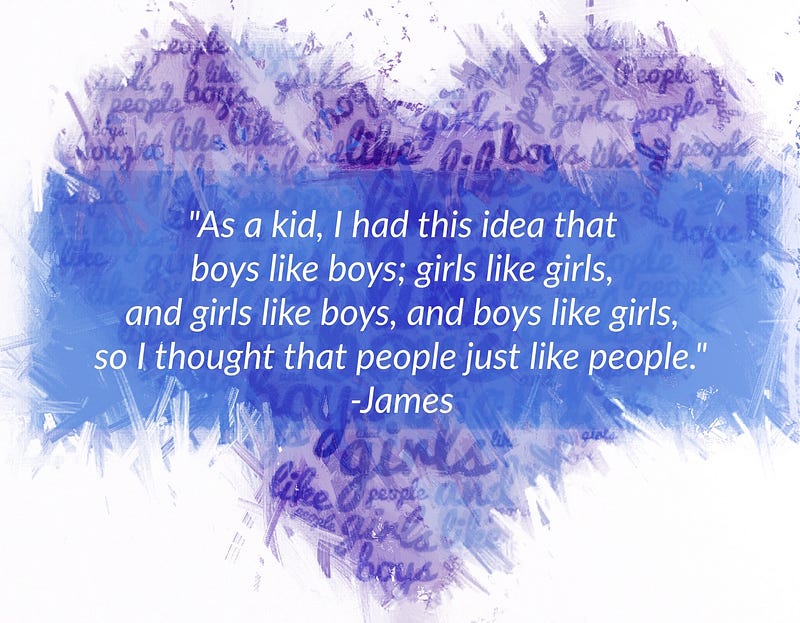

In addition to feeling detached and out of place in his home life, James also experienced feelings of isolation among his academic peers as a result of his sexuality.

“I’m a homo, but I didn’t really know the term ‘gay’ until elementary school, and even then it wasn’t clear, but I knew gay was bad, so I always denied it — I guess, at a certain point, I felt ashamed that I was ‘different,’ but I’ve always known.”

James tried sex before he tried medication. His first time having sex was with a sandy blond-haired, blue-eyed friend that he often went swimming with: “When we were both 13, we started fooling around, ‘exploring.’ It was just, ‘I dare you to do this, or I dare you to do that,’ and then it got sexual right quick.”

Even with his first encounter, James had the insight that sex required a barrier of some sort and creatively improvised in the absence of the traditional prophylactic.

“You know those bags that you put fruit in when you go shopping? Essentially, we gave each other head, but we wrapped our dicks in that so when we came, that’s what we came in, instead of a condom because we didn’t have condoms … And that’s how it started,” said James.

While the existence of sex addiction remains a controversial subject, an increasing amount of professionals recognize the cyclical behavioral patterns that sex addicts exhibit as consistent with any other form of addiction. The cycle of sex addiction typically presents as follows: indulging in risky sexual behavior; feeling guilty or remorseful for doing so; resolving to change; and then relapsing by giving into the cravings repeatedly.

James’ first awkward sexual encounter in high school started the cycle of seeking relief by having sex with a plethora of varying partners, in every location he could: parent’s cars, school locker rooms, park restrooms, and church confessionals — what began as an innocent exploration of “I dare you to do this, or I dare you to do that” with a childhood friend, had by his late teens and early twenties descended into the administration of pain for sexual thrill with complete strangers.

According to Psychology Today, BDSM, which is an abbreviation used to represent “Bondage and Discipline, Dominance and Submission, Sadism and Masochism” has several categories in relation to sexual behavior: “physical restriction,” such as bondage, handcuffs, and chains; “administration of pain,” such as spanking, caning, and putting clothespins on the skin; as well as “humiliation,” the use of gags or verbal degradation.

For James, who enjoyed the “administration of pain” in the form of being beaten, the most appealing thing about BDSM was the sense of control it offered him.

“My sexual play gave me the control when I didn’t have control in my life. I could dictate the situation and be the one to say, ‘okay, we’re going to do this’ with respect, as long as the other person was consenting — Plus, orgasm released the endorphins that I desperately needed, even if it just lasted a second.”

In the moment of having sex, James experienced the closest thing that he knew to having “fun.”

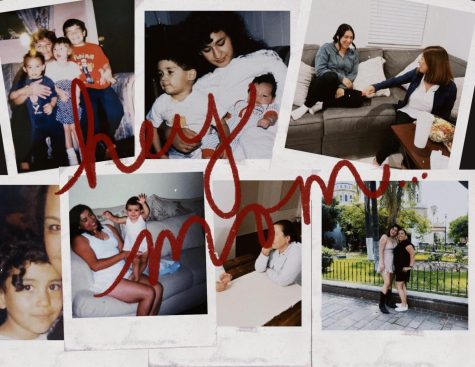

During childhood, James remembers always being sad and never really feeling “happy, happy.” He struggled with feelings of isolation in addition to sadness, and at five or six years old, when his parents, who “fought all the time,” were beginning to go through a divorce, James often fantasized about his “real family” coming to his rescue.

“I used to wish that the people in my family weren’t my family and that I had my real family playing a joke on me, and that my real family would come.”

Throughout his sexual indulgences, James tried to both escape the hurt that he felt and manage his risks by doing his best to keep other possible addictions in check. In so doing, for the most part, all of his sexual encounters had not only been enjoyable — but they had also been the only thing that he found powerful enough to lift the fog of depression.

“I used to get drunk a lot, like stupid drunk, black out drunk, and that scared me … I used drugs too for a while, but it wasn’t as frequent, and I mostly did it because I just wanted to have fun with my friends … But sex was the only thing I found that could really take me away, fully distract me, and lift that foggy feeling.”

However, the breath of fresh air — the momentary break of clarity and elevation to a state of enjoyment — didn’t last long. As both the stranger and rush of endorphins flooding his system left, his post-coitus high rapidly faded away. Even sex was not enough to prevent the fall, descending back into the arms of the foggy state of depression where numbness was always waiting to grasp him yet again.

James drifted into that fog one November day, after spending the night with a Hollywood stranger. While in its clutches on his bus ride home, he decided that would be the day he ended his life.

Without so much as a note, James returned to his room, grabbed “actual rope that you see people making nooses out of,” tied a knot, and closed one end of it in his bedroom door and fastened the other around his neck.

While trying to slam the door on his life — a life of depression and desire to escape — the rope tightened against his throat and the darkness of unconsciousness took him. On the brink of asphyxiation, he felt himself awaking to the shake of his convulsing body against the door.

In a fraction of a second, a new thing flooded his veins, adrenaline and the carnal instinct to survive.

James managed to remove the rope, which left him scared, but alive. Still trembling, he opened the door, removed the rope, and collapsed into the realization that he wanted to live, but something had to change.

“I had just had it. I’d had enough because I really saw how close I had come — I almost died. If I had just waited like another few seconds, then that would have been it. I would have been dead, and I wouldn’t be here.”

Afterwards, James had a chat with himself: “You know what, silly James, this is what you’re going to do — you are going to get better. You can’t keep living like that.” His pep-talk with himself, backed by 26 years consumed by “fog,” was enough motivation for him to seek psychological help and take the necessary steps to make himself feel better in ways aimed to break the vicious cycle of addiction.

It took until about January of this year for James to really feel the upswing of positive change, which he credits to religiously taking his medication.

“I thought that if I just took my pills then bloop, things would just get better, but they didn’t. I had to take my pills and then wait for things to get better, for my pills to actually kick in, but when they finally did, it was just like whoosh, such a difference,” said James.

One of the major differences James noticed was a declined interest in his more extreme sexual activities. “When I was having that sexual interaction with the BDSM, and I was getting beat — because I never hurt myself really like that, but someone else was hurting me — the pain made me feel good. Now that I’m on my medication, and not as severely depressed, I’m not into it that much anymore,” said James.

Previously, James wouldn’t openly discuss how he felt; instead he bottled up and hid his emotions, which contributed to his inward sense of isolation and his need to outwardly express his pain.

“Early on, I learned how to fake my emotional state, to make people believe that everything was okay, and that’s how I got by so long without medication … I don’t think anybody really knew the extent to which I was depressed. I think my mom at some point knew, like ‘maybe you have depression,’ but I think nobody really knew that it was clinical and severe,” said James.

The severity of James’ depression made daily routine tasks feel impossible.

“I was semi-catatonic at times. I would just lay there, unable to do much. I wouldn’t shower, wouldn’t brush my teeth, only get up to use the restroom. I wouldn’t eat. I had a lot of suicidal thoughts, and a lot of plans to end my life, and a couple of times I tried — the last time, I should have died, and I didn’t, which worked out for the better,” said James.

With medication, he finds himself able to share his experiences more freely. “Now my coping mechanisms are kind of different. I let myself cry more. I’m willing to just talk about it, like ‘I’m feeling really depressed right now,’ and I realize that the feeling that I’m having right now, in the moment, is not permanent because I have my medication, and now I know what life is supposed to be like,” said James.

When James finally got his medication, he had been depressed the majority of his life. He didn’t know what life felt like without depression.

With medication, he experiences life much differently. He allows himself to “just feel depressed,” to reason with himself on days when he doesn’t feel like showering, and to reach out to talk with loved ones when he is having a bad day.

“My medication has helped me step out of that fog and go on to different things. It’s allowed me to see how beautiful life is, and how amazing things are,” said James.

Although James still enjoys having sex because “sex is great,” his coping mechanisms are different, and he no longer feels the need to immediately turn to sex as a source of relief.