Unarmed And Gunned Down

A mother continues to fight for her son’s justice

Story and photos by Pablo Unzueta

For the past year, we have heard a lot of stories about police encounters that ended in a fatality. One of the biggest stories yet is the shooting of an unarmed young man, 18-year-old Michael Brown, who was shot to death by Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson. Protests have been taking place in Ferguson for over a month now.

Just three days after Michael Brown was shot, Ezell Ford, a 24-year-old man with a history of mental illness, was walking down the street on a Monday night when two Los Angeles Police Department officers stopped him. Shortly after an altercation, Ford was shot and killed. Why the LAPD officers opened fire is still unclear; Ford was unarmed.

Most of these cases rarely gain media attention or even public recognition. However, these recent incidents have allowed mothers and family members to speak out in protest. Perhaps it will be the only time these families will get a public reaction. Eventually, these protests come to an end. So what happens next? Do we move on and wait for another cop to kill an unarmed human being? Do people really care or are they just caught up in the hype? I’m not sure. We seem to be in an age where the media dictates our behavior and beliefs.

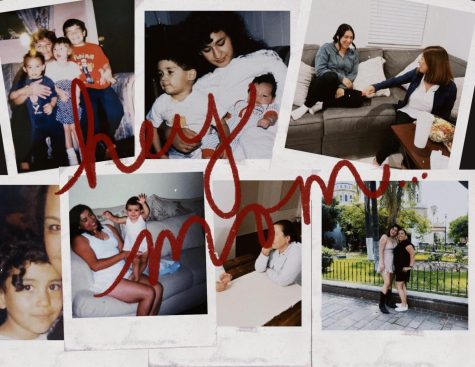

I first met Vershell Hall during a protest on Aug. 17 for Ezell Ford just outside of the Los Angeles Police station on First Street. I listened to her story. Her son, Richard Ray Tyson, was gunned down by an Inglewood police officer on May 9, 2007. He was 20. The speech was brief, emotional, and agonizing. She talked until her words could no longer escape — trapped between the distress of losing a son and desire for justice. She spoke loud with courage and rage.

“My son was riding his bike; he had just bought a shirt to wear to the studio when a police officer stopped him and assumed that my son had a gun tucked beneath his sweater. They shot him in the back of his head twice! My son was innocent; he didn’t deserve to die. I want justice!”

With her right hand she gripped the microphone tight, while she held a framed picture of her son. Kelly Kunta, an activist who fights against police brutality, comforted her briefly as she began to cry. The large crowd surrounding her dispersed to march. Hall stood alone wiping her tears with a tissue on the sidewalk. The picture of the young man smiling was kept tucked beneath her arm.

From that day on, I became driven by Hall’s world of grief. She welcomed me inside her home several times to discuss her son’s death. She believes Richard Ray Tyson was murdered ‘execution style.’ “The autopsy reports that bullets were fired at close range, slightly downward position, so that meant my son was on his knees.” Hall was at work when she had received the phone call that her son was dead. “Three days before, we had a little argument and something kept telling me to call Richard. I never got the chance to say I was sorry. I can’t even explain that feeling.”

Hall, who has six children, said that Richard was her third to youngest son. “Richard loved dogs. Oh my god. He would bring home a skinny dog and feed it just so the dog wouldn’t starve. He had a pleasant personality with a heart of gold, who would take his shirt off and give it to you — that’s the kind of son I had.”

The Federal Bureau Investigation examined Tyson’s case for one year and a half and just two days before Christmas they dropped the case. She explained: “We sat down on the couch and they told me, ‘Ms. Hall, your son was killed execution-style, but there is not enough evidence to prosecute the officer.’ Now, the autopsy report says that bullets were fired at close range: back to front, back to front, back to front, back — come the fuck on man… come on! Four times back to front. What is that? Not enough evidence?”

According to the Inglewood police statement, Richard Ray Tyson was riding his bike on the sidewalk when police officer Zerai Massey stopped him for a minor infraction. Tyson then ran into a residential back yard; that’s when officer Massey fired six times, killing Tyson. The officer said the suspect had a bulge near his waist, which was a T-shirt. No drugs were found.

The first bullet entered through the back of the head (that didn’t kill him), the second bullet went to the back of the neck (that didn’t kill him either), but the third bullet, which entered through his back torso killed him.

“The first two shots didn’t kill him, but I’m sure he felt like he was on fire, because I was told that’s what it feels like when you get shot,” Hall said.

Massey, an 11-year police veteran, had been in four separate shootings involving unarmed civilians throughout his career.

One of the fatal shootings involved a homeless man who was shot 47 times just one year after Richard Ray Tyson was killed. In August 2008, Massey was placed on administrative leave and required to undergo “supplemental training” before being allowed back on the street. He currently maintains his job as an Inglewood police officer and in July 2013, was awarded the Attorney General Award of Commendation.

An estimate by the Badge of Life, says that one of eight police officers have symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, having experienced violent crimes and shootings. However, mental health check-ups are voluntary. So is PTSD playing a role in police wrongdoings?

Seven years after Tyson’s death, Hall is embarking on a new life with art as her meditative therapy. She is aspiring to create custom fabrics for clothing apparel. “I have this creativity surging through my veins. Once I make enough money, I want to get justice for my son. If he was still alive he would be well off.”

Tyson loved to compose music. The day he was killed, Tyson was on his way to the studio to record the lyrics he had written. Hall’s son never made it. “I didn’t realize how cold-blooded this world was until my son was murdered. But God willing, I will give my son what he deserves.”

Substance is a publication of the Mt. San Antonio College Journalism Program. The program recently moved its newsroom over to Medium as part of a one-year experiment. Read about it here: https://medium.com/substance/the-experiment-be947b2ba13e