Homeless Students Struggle in the Shadows

Being in college is tough enough without worrying where your next meal is coming from.

It’s a familiar scene near highway junctions. The cardboard signs, the dirty, sun-stained faces, and the religious sentiment, “God bless.” Familiar, yet uncomfortable. It is easier to ignore the person standing near the offramp and pretend not to see the look of desperation in eyes that squint from the brightness and heat of the sun. It is easier to keep driving.

Many people do choose to avert their eyes, inch their fingertips towards the lock buttons of their vehicles, and slowly roll up their windows rather than confront the legacy of social injustice staring straight at them. However, rolled up windows and locked car doors are not enough to completely brush off that sneaking feeling of shame, that lump in the throat that won’t go down, that empty hallow feeling sitting in the pit of the stomach near the seatbelt. It is that uncomfortable body’s reaction acknowledging that a fellow human being — someone’s son, daughter, or hero — is begging on the side of the road.

As a means of justifying the lack of charity, self-reassuring thoughts may surface.

He will probably just buy alcohol, or drugs if I give him money.

I bet she’s not really homeless, just faking, a scam artist.

They are just too lazy to get real jobs.

Even these thoughts, on a deeper level, do not excuse the issue from weighing on the conscience. It’s not until the signal changes to green and the grungy stranger is no longer visible in the rear view mirror that the lungs release the breath that began retracting as the tires neared the person being reduced to background scenery.

The social barrier provided by closed car doors creates a sense of distance, which stops the hard questions from fully forming in their minds.

What is his story?

Where is her family?

Why does someone who fought for home and country beg for work, food, and a place to sleep on the side of the road?

Harder yet to face is the fact that this is only one of many faces of homelessness. Much worse than the idea of the homeless stranger blending in with the pebbles and weeds is the idea of the young homeless student.

Homelessness has become nearly synonymous with hopelessness. The homeless stranger is readily criticized from the distance. However, the student is often praised for striving toward and dreaming of self-improvement.

Thus, it is less common to pair homelessness with words like “student,” “determined,” or “lifestyle choice,” not because the combination does not exist, but because these individuals often keep their conditions secret. In fact, it is sometimes kept in such secrecy that they may not even admit to themselves that they are “homeless.”

“In my 20 years of teaching, I’ve probably had about 20 homeless students in my classes that I’ve known about, and they usually just think of themselves as ‘couch surfing,’ ‘sleeping in their cars,’ or ‘not having a place right now,’” said John Brantingham, a professor of English at Mt. San Antonio College.

Brantingham shed some light on the mentality of homeless students in relation to their homelessness. According to Brantingham, students do not usually see themselves as being homeless. To them, homeless people are the ones pushing around shopping carts and collecting recyclables. They usually just see it as something temporary.

“One of the biggest challenges I’ve faced as a professor when it comes to homeless students is getting them first to recognize that they are homeless and then getting them to understand that there are resources, possibly, to help them,” said Brantingham.

The social stigma surrounding homelessness often prevents students who recognize themselves as homeless from seeking much needed help and resources. The social stigma and personal shame of being homeless presents a unique set of challenges for receiving resources, remaining optimistic, and continuing to take steps toward achieving educational, career, and life goals.

Even within the academic setting of a college or university, which teaches research skills and values student success, individuals may still shy away from seeking help, and professors or staff may be ill-prepared to help those who do.

This was the case for Ryan-Sally June, a 25-year-old literature major who recognized herself as homeless and began actively searching for resources, only to find that there were little to none available to help a student who was just out of a job and needed a place to call home. To get help, she would have needed to have an addiction problem. She has been homeless for about two years now.

At first, June didn’t admit to herself that she was homeless; she lived in her car, before it was repossessed, and then she found other places to spend extended amounts of time between classes, like the 24-hour McDonald’s near campus. She would use the fast food restaurant to study, take naps, and either ride the bus to or walk to before or after classes. After the first six months, she recognized that she was homeless, but it didn’t deter her goals.

“Most people see homeless people as lazy, and say, ‘oh, why don’t they just go get jobs?’ when they see homeless people on the streets. What they don’t realize is it’s not that easy,” June said.

June added that most job applications require a permanent address. Even once a person figures out an address, getting a job is not easy. June sent out 18 applications every day for several months and only heard back from two. According to her, it’s just that hard, and the people on the streets have simply given up.

“I haven’t reached that point. I’m in school. I have a future,” said June.

Society often both overlooks and frequently lacks adequate resources to address the unique challenges of students, who are good students, not criminals, and not drug addicts, but are still without a place to stay.

James Stone, professor of political science at Mt. San Antonio College, said that his first instinct is to help his students.

“As a professor, if a student came to me and said that he or she were homeless, I’d want to help, but I’m not sure what I could do, or even what my role would be to try to help out. I’d probably check with Student Life or the Health Department to try to help the student find some resources.”

Some of the first places that professors think to refer students to for resources on the Mt. SAC campus are the Student Life Center, Financial Aid Department, and the Health Center. However, for one staff member, who wished to remain anonymous at the Health Center, having a homeless student come to them to request resources was unheard of. “Students don’t admit that they are homeless. They just don’t, and I’ve been working here for a long time. No one has ever admitted that to me. They might confide that during counseling, but not at the front desk.”

Professor of Journalism and Adviser of Student Media Toni Albertson said the help is non-existent.

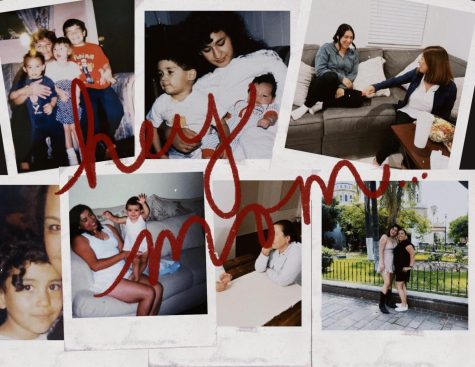

“I learned that one of my hardest working students was living in her car for nearly two years,” Albertson said.

Albertson called Student Services and was given a list of organizations to call.

“It was so frustrating to speak to organizations who would go down the list of criteria that needed to be met before they could help — “Is she a drug addict, a single parent, disabled — the list went on and on and she met none of them. She was just homeless and needed shelter. I guess that isn’t enough.”

Understanding the sensitive nature and social stigma of being homeless, it can be difficult for professors or staff to know what to do, or how to approach a student who confides that he or she is homeless.

Ryan Hunt, professor of United States and European history at Mt. San Antonio College, once had a student whom he suspected of being homeless. He recalled that the student would attend class without wearing any shoes. Casually, he decided to inquire about why the student wasn’t wearing any shoes, and the student assured him that he wasn’t wearing any because he didn’t like shoes.

“I wouldn’t expect every professor to try to help a student find resources in the event that she or he were homeless. I’m not saying that I wouldn’t try to help out, but I wouldn’t expect every professor to. It’s not in the job objectives for the position, and it’s just not something that we are trained for or prepared for,” said Hunt.

Whether the student was in denial of a difficult home situation or simply did not like shoes, Hunt did not know for certain. However, he didn’t bring up the subject again because he didn’t want to insult the student by digging any deeper. Hunt noticed that the student began to wear shoes a bit more, later on, after he had inquired about it.

The issue of homelessness is as complex and diverse as the people experiencing it. Not all people are the same, nor are all situations of homelessness the same. The complexity of homelessness, social nuances, and personal ideologies all contribute to why homelessness is still an issue which rarely becomes a focal point of mainstream public discussions. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to the issue of homelessness, just as there is no singular shared cause of a person becoming homeless.

The key societal question is, What can I do about it? What should I be doing about it?

This is central to the issue of homelessness, and specifically resolving homelessness for students. Francisco Gomez, Professor of English at Mt. San Antonio College, explained why he believes homelessness and personal levels of responsibility when interacting with homeless students vary, depending on the individual and the circumstances.

“Many people like to talk about education within a set context, like it exists in a vacuum. It doesn’t; life doesn’t. It’s not like someone can turn off life while in class,” said Gomez.

In his experience as a professor, Gomez has had students confide in him that they were homeless in the past, but he has never had a student tell him that he or she is currently homeless. To him, it is evident that the social stigma attached to being homeless is a major contributing factor to why a student may not feel comfortable sharing that they were homeless until after the fact. According to Gomez, if a student shares that he or she was once homeless at some point in life, after the fact, then the student may personally feel that he or she has walked away from the stigma to a certain extent.

“The social stigma of being homeless exists. To claim that it doesn’t would be naïve at best. All one has to do is look at any bus stop to see how much society just ignores those individuals,” said Gomez.

He equates homelessness to any other traumatic experience in a person’s life. Gomez said that while a person is going through something traumatic, he or she may not feel comfortable sharing the experience, and directly confronting a student about being homeless could be misconstrued as being rude.

“It is one thing to be there for a student who confides in you, and it is another thing to demand the student to divulge something that he or she may not want to,” said Gomez.

Gomez added that a professor or individual’s personal level of responsibility to the student who confides that he or she is homeless varies — as the situations and causes for homelessness vary greatly. Gomez considers questions like: Is it a battered woman? Is it a child who felt he or she wasn’t safe? Is it the case that someone got kicked out of his or her house? Is this someone who left his or her spouse?

For Chris Jang, a former Mt. San Antonio College transfer student who currently attends the University of California, Berkeley, homelessness was a strategic economic choice. After splitting up with a girlfriend who he had been sharing residence and rent with, Jang began what would become six years of homelessness, by choice.

After he and his girlfriend broke up, it wasn’t economically feasible for Jang to continue renting his old place on his own. Not wanting the hassle of finding a new roommate, he moved back in with his parents. Due to the small size of his parent’s apartment, he slept in the living room, which lacked adequate space and privacy to satisfy his tastes, and his ego was hurt by having to move back in with his parents.

“After forging my own way and living on my own in the world, moving back with my parents was a blow to my pride. It was embarrassing, and pretty taxing. I had a big vehicle and some money saved up, so I just decided to move into my car,” said Jang.

At the time, he was into fishing, and decided to drive to Newport Beach, live in his car, and fish for six months to a year. To him, the experience was just like a really long vacation. He eventually decided to move on from fishing at the beach, and return to school.

“I was actually proud of being homeless at the time. It’s a big difference between being homeless by force, and being homeless by choice,” Jang said.

One of the added levels of complexity to the issue of homelessness is the issue of personal pride. While Jang took pride in being homeless, many others do not. For them, homelessness carries an engrained awareness of social stigma and personal shame. If a professor were to attempt to inquire about a student’s living situation, then the professor may be met with a highly defensive or abrasive response.

Gomez considered how he would respond in the hypothetical situation of being homeless, given that he was raised with a strong sense of personal responsibility to take care of himself.

“I can tell you I would think ‘Well, I’m at college. There’s a locker room. I can shower. Do I have a car? Can I change my clothes? Is there a laundry mat nearby so I can wash them. I’d sure as hell make sure that no one knew because that is just the type of person that I am. If anyone even suspected me of it, I would be extremely defensive because that’s just the way that I was brought up.”

There are differences in the reasons why students are homeless. Attempting to address the issue of homelessness is complicated because, like most things in life, the right course of action depends on the circumstances. To give a generic answer to the problem of homelessness would be to oversimplify the complexity of the issue — and, according to Gomez, it would be a disservice.

“The homelessness in and of itself is never going to be just that. It’s never going to be the person just doesn’t have a place to live. There are going to be a whole lot of other issues that compound the homelessness, so to try to treat the homelessness without those other compound issues is disingenuous at best,” said Gomez.

There is no one uniform answer. It depends on the student. It depends on the context. The level of personal responsibility, and the extent to which a professor might feel compelled to help a student depends on the circumstances and the student. Students have different levels of comfort when it comes to interacting with professors, and there is a difference between responsibility and being overbearing.

To resolve the issue of homelessness, the focal point cannot be simply that the individual is homeless. The uncomfortable question, “Why is this person homeless?” must be addressed.

“It depends on the student, like anything else. What one student perceives to be survivable, another student may perceive to be insurmountable,” said Gomez.

For Jang, transferring to the UC Berkeley marked a new beginning for him. Desiring the more traditional college experience, he opted out of the chosen lifestyle of being homeless, and decided to pay rent for the first time in several years.

As for June, being able to go from worrying about how to live from day-to-day, week-to-week, month-to-month, and then to yearly is progress.

“I’m not there yet, but I’m doing better than worrying how to survive day-to-day,” said June.

Substance is a publication of the Mt. San Antonio College Journalism Program. The program recently moved its newsroom over to Medium as part of a one-year experiment. Read about it here.