Woman Without a Country

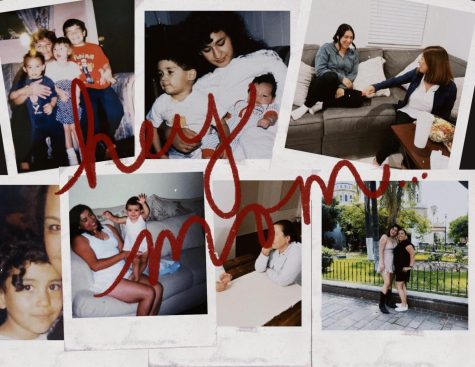

Born in L.A. and taken to Argentina as a child, Beatrice is undocumented with no place to call her home.

Story and videos by Jessica Fuller, Albert Serna Jr., Adolfo Tigerino, and Rich Yap. Photos by Zea Huizar

Standing at the ledge of a pool, 7-year-old Beatrice contemplated her life. The torment of abuse from her father consumed her thoughts; a pain exasperated by the blind eye of her mother. Her toes crept over the edge. As a Catholic, she knew the consequences of ending her life, but it didn’t matter. Nothing mattered anymore. It was her only way out. She looked over each shoulder. Freedom felt so close. Closing her eyes, she leaned forward and fell into the chilly water. The world began to mute and Beatrice started to feel free. But before the water overtook her, she felt something tighten around her arm, pulling her. She gasped for air as her head breached the surface. Someone had pulled her out.

Her closeness to death did not frighten her. Rather, she was upset that after gaining the courage to end her life, someone had taken that away from her.

Even as a child, Beatrice was plagued by a sense of not belonging. This was the first of many attempts Beatrice made to end her life. At 56, she’s lost count. Her story is long and tragic, riddled with defeat after defeat. And for most of her life, she’s lived out of her car surviving on gas station hot dogs and Coke. Yet, Beatrice clings to the sliver of hope that one day her lifetime of struggle will be worth it — that her suicide attempts failed for a reason.

For the last four decades, Beatrice has tried to become a recognized U.S. citizen. Although her story sounds similar to many others, hers is markedly different. Beatrice was born in America.

Beatrice spent her childhood dreaming of America, the home she was torn away from as an toddler. She felt a keen and inexplicable connection to it. She knew she belonged there. Beatrice’s longing for a life in America finally made sense when her aunt revealed that she had been born in the United States. The abuse and neglect from her family only fueled her determination to find her way back.

“Every time I heard the train blowing [its whistle], in my mind I was jumping in it and going and seeking freedom,” she said.

Though American himself, Beatrice’s father loathed his country. As a child, his family, who had emigrated from Spain to the United States, was deported to Mexico. Years later, they re-entered the country. He suffered years of discrimination because of his dark skin, which only inflamed his resentment. He grew up to idolize infamous leaders like Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong. He hated America and his children would suffer for it. He kept them from being born in a hospital, and in April of 1961, Beatrice was born in her family’s Lincoln Heights, California home.

She was never issued a birth certificate or social security number. There was no record of her birth in the state or even the country. In the eyes of the United States, Beatrice was not an American citizen.

Two years passed before Beatrice’s father forced them to move to Argentina. Her life there was marked with heartbreak. Her earliest memories are of her father’s verbal and physical abuse — his violent temper triggered by even the most trivial acts.

One night, Beatrice lay asleep in bed, wearing only a t-shirt and shorts to withstand the thick summer heat. Her father came into her bedroom, loosened the belt from his pants and began to strike her. Over and over he whipped the leather down upon her bare skin.

She couldn’t recall exactly what caused her father’s outburst. “Something silly probably, like school,” she said.

Upon seeing Beatrice’s legs covered in bruises and welts the following morning, her mother stroked her daughter’s hair and gently kissed her forehead before sending her off to school.

Beatrice suspects her mother, who was also victim of this man’s abuse, was too afraid to act out against her husband and too religious to divorce him. Beatrice’s two brothers offered no solace either. They, too, tormented her.

It was this silent suffering that compelled Beatrice to seek escape, like her suicide attempt as a child. Growing up, she decided that this would not be her life, that it would not defeat her. She wanted to go to college and make a life for herself. She wanted to be a physician, to treat people and help cure them of illnesses.

For years, she plotted her escape to America, longing to jump on the train as it passed by her home. And one day, she did escape. With only a plastic bag of clothes and money she had scrounged up, 16-year-old Beatrice left everything she had ever known to find her place in America — to reunite with her home.

She understood that running away was dangerous — that it could cost her her life, but freedom was worth dying for. The idea of staying was worse than death.

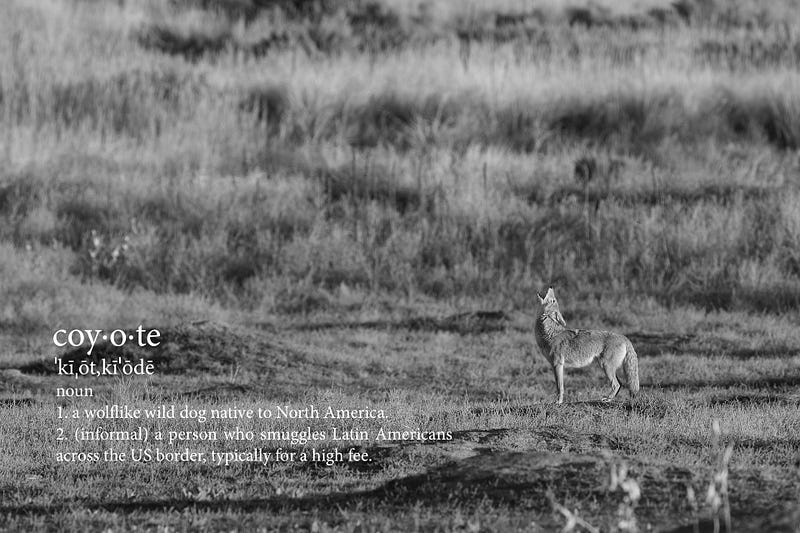

Beatrice traveled nearly 10,000 miles across South America and Mexico to Tijuana before attempting to enter the United States. She didn’t speak English then, only Spanish and Italian, which she learned from her grandmother who was born in Italy. She stayed in Mexico for several days before being approached by someone who offered to help smuggle her into the U.S. The first time she tried to cross the border, her group was quickly spotted, picked up by authorities and brought back to the Mexican border. It could have ended much worse, but it was worth the risk. She had made it this far and there was no giving up, no turning back. A few weeks later, she tried again.

On a cool November night, teenage Beatrice and two others, led by two coyotes, walked several miles from Tijuana into the dark desert where they met a truck driver who was supposed to take them safely into the country.

They were told that the driver had connections to the government, so their safe passage into the states was almost certain. When the group met the driver, they climbed into the cab of the truck, closed the curtains behind them, and headed up the highway. A few miles in, the truck began to slow. The brakes squealed as the semi-truck came to a stop. A breeze swept through the cab as the driver got out of the truck and slammed the door behind him.

Beatrice’s heart began to race as she heard the muffled conversation between the driver and another man. Still, she remained hopeful that it was all part of the plan. Moments later, the door swung open and the driver pulled himself back into the truck and continued driving. “We’re clear,” he shouted over his shoulder to the group. Beatrice had finally made it back to America.

“I can recall when the driver said, ‘We’re clear,’ and he opened the curtain of the cab, and just seeing, even the stupidest things, like signs or Shell gas station — it was just…I cannot describe it. But it was just almost like being in heaven.”

Beatrice was finally home, but America did not welcome her warmly. Starting a new life here was more difficult than she had imagined. With no documentation of her birth or record of her life in either the U.S. or Argentina, she was unable to claim her citizenship as an American or file for asylum. So, for the last 40 years, Beatrice has struggled to survive in the United States, living most of her life in a car.

Beatrice’s desires were modest. She wanted to go to college, get a job, live in an apartment. She wasn’t looking for a handout. She was willing to work hard to achieve the American Dream, but without a home, money or documentation, she was at the mercy of employers willing to hire an underaged, undocumented girl. But young Beatrice was determined.

First, she worked as a gas station attendant. The owners sympathized with her situation, and let her sleep in the back room of the station. When that ended, she worked as a dishwasher in a restaurant. She attended night school and earned her GED, learning English along the way. She continued on to Santa Monica College where she earned an associate degree in graphic design in 1986.

All the while, she was living out of her car, parking overnight in gas stations where she had made friends with the attendants. When it was hot out, she tossed and turned, sweating through the night. When it was cold, the warmth of her breath fogged the windows. Yet, despite her circumstances, Beatrice was content with her freedom and even optimistic about her future. She believed that if she worked hard and continued her education, she would be able to make a legitimate life for herself. She couldn’t imagine how unforgiving life would be.

“It was just exciting. It was like things will change eventually. I had energy too. Back then, I was able to not go to sleep for two or three days because I was happy and had energy and the sense and the hope that that was going to end. I didn’t have fears back then. I was happy. I was in control of my life, making decisions on my own and getting more education so that I would be able to succeed.”

It would take years of disappointments to dull Beatrice’s optimism, but at this time, life was an adventure. Her childhood dream of becoming a doctor never left her. In 1986, she applied to UCLA for pre-med and was accepted. But her excitement turned to doubt and dread. Realizing she wouldn’t get far without documentation or money for tuition, she folded up the acceptance letter and stored it away.

In 1988 at 27, she moved to Dallas, Texas with a college friend who was starting graduate school. The student loans covered the cost of rent for them both, so it was an opportunity she didn’t want to pass up.

Beatrice quickly found a job transporting cars across the country. She could have taken the fastest route to her drop-off destination, but favored the scenic route. She sacrificed sleep, driving nonstop to make it to her destination on time so she could experience the country that she had dreamed of for so long. When the company went under a year later, Beatrice lost her job.

When her roommate finished her degree in 1990, Beatrice went back to Los Angeles, again with little and nothing to her name. She struggled to find work and a place to stay, so for three months she slept on the bus. Each night, she slumped over on a plastic bench near the back, rested her head against the window and clung her belongings to her chest. Some drivers let her ride through the night while others kicked her off, leaving her to wait for another bus. Each time she hoped that the next driver would be more compassionate.

One night when Beatrice was kicked off the bus, she was attacked. After ignoring the demands of a homeless man to give him money, the man lunged at her. He tried to take her bag and when she pulled back, he bit her hand. She got away, realizing how dangerous living this way had become. Every night was uncertain, and again, she felt like she had nothing to live for. At 25, she tried for a second time to take her life.

She tried to starve herself of food and water until her body shut down, her organs failed, and she died. She knew it would be excruciating, but several days of pain to end it all seemed worth it.

But the pain of thirst and starvation was too much for her to stand. As she laid defeated, Beatrice contemplated her life. She wondered if she had come this far to give up now. She forced herself to believe that she could still make something of herself.

Late in 1990, Beatrice found a job as a taxi driver. Each day was a stressful pursuit for customers with the car lease payment looming over her each month. But after a few months, she built up her clientele and was able to pay the lease and provide for herself.

This was the only time in Beatrice’s life that she was able to afford rent and buy food and clothes for herself.

She also went back to school, attending Citrus College, where she was introduced to newspaper design. She was a talented designer and spent countless hours working on projects for the paper.

After 11 years, her job as a driver, too, came to an end. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 hit the taxi industry hard and the rise of the internet prevented Beatrice from renewing her license. No social security card meant no driver’s license, and without a license, employers refused to hire her. After her savings were depleted, she was forced to live in her car.

Beatrice tried over and over to become a recognized U.S. citizen. People she thought were friends took her money, promising that they would help her become a citizen. She didn’t qualify for help that was only offered to single mothers, drug addicts or alcoholics. She applied to programs that claimed they could help people in her situation, but her paperwork was denied several times. She was told that if she went to the immigration office, she would be detained or deported.

After nearly 35 years of trying and failing over and over agin, Beatrice lost hope for a better future. She believed that no matter how hard she worked, no matter who she turned to for help, she would always be let down. Her dream of leading a normal life seemed too far out of reach. All she could do now was take what she could get. Yet, despite countless sleepless nights or the depths of hunger, Beatrice refused to beg for money. She was simply too proud to take a handout.

“I prefer to earn my money,” she said.

In 2002, she found another job at a gas station, living out of her car in the station parking lot. After four years, the gas station changed ownership and she was laid off. She believed that education was her only way out of this cycle, so she tried college again.

In fall 2006, Beatrice attended Los Angeles City College where she took journalism with Faculty Adviser and Assistant Professor of Journalism Rhonda Guess.

“She has super skills. She didn’t just have super skills — she has imagination and creativity,” Guess said of Beatrice. “There’s always something going working in her brain. She’s an idea person, concepts, she whips up things, creates things, surprises you. Nothing is ever the same, nothing is ever routine.”

Beatrice became a designer for the school newspaper, The Collegian. Her designs helped the newspaper win collegiate journalism awards at numerous regional and state competitions.

It wasn’t until Guess invited Beatrice to attend a conference out of state that she learned of her situation. Beatrice reluctantly admitted that she couldn’t fly because she didn’t have a driver’s license or any type of government-issued identification.

“She doesn’t tell a lot of people,” Guess said. “If you look at her you would never know. She doesn’t come in disheveled. She seemed like she had a normal life away from the college.”

But Beatrice didn’t have a normal life. She was still living in her car, earning money sporadically by doing small projects where she could find them. She ate fast food and gas station hot dogs because it was cheap and easy to come by. When she wasn’t on campus, she worked anywhere she could — at the mall or in the library until it closed and she was forced to leave.

Beatrice’s situation weighed heavily on Guess. While she was going home each night after class to sleep in her bed, Beatrice was going back to her car that was parked in an alley, fighting hunger and trying to sleep. Guess wanted to help Beatrice, but her unique circumstances left her at a loss.

“I do not believe that we are living up to our creed,” Guess said. “You know what it says at the bottom of the Statue of Liberty when we ignore people? When we don’t really look for ways to solve these problems? When we don’t allow places for people to come in out of the shadows? It’s a sign of a weak or sick society. We need to embrace them with people who want to work, want to be productive.”

In fall 2007, Beatrice also began attending Mt. San Antonio College in Walnut, California and sought a student designer position for the campus’ print newspaper, The Mountaineer. Here, she met Journalism Professor and Student Media Adviser Toni Albertson who would become her advocate.

“I’ll never forget the day I met Beatrice. She told me that she was going to make me an offer I couldn’t refuse,” Albertson said. “She was right. I took one look at her designs and was thrilled to have her on our student staff.”

At first, the newspaper staff was resistant to Beatrice. She was much older than the other students and their personalities often conflicted. But her skills and dedication were undeniable and she soon became an integral part of the staff. Her peers relied on her for their designs and she never failed to come through. As the staff members got to know Beatrice better, they had the utmost respect for her. Some, like Adam Valenzuela, a newspaper staff cartoonist, became her close friends.

“I just think she’s a surgeon when it comes to design, everything she does.” Valenzuela said. “It’s fun to watch her to make the slightest changes. She works fast. That goes to show you how much of an eye she has for the detail and rendering because she works nonstop.”

Despite the severity of her situation, Beatrice never complained or let on that she was suffering. She worked on the paper for two years before anyone there knew about her personal life. Albertson sensed something was off, but it wasn’t until Valenzuela mentioned to her that he was concerned about Beatrice. The two had bonded over their artistic abilities and their love for classic rock. One night after a late newspaper production, Valenzuela gave Beatrice a ride back to her car, which was parked in an alley. He suspected that she was living in her car.

The next day, Albertson approached Beatrice about her situation, where she reluctantly admitted that she’d been living in her car for the last two years. Albertson was stunned. She admitted that she thought a person who’d been living in a car for two years would find it difficult to shower or keep clothes clean. But Beatrice was a proud woman who refused to let on that she was struggling. She would come to school in the early morning to shower in the locker room if she needed to. Her clothes were clean and she was always presentable. She showed up on time and always met her deadlines. She never complained that she was hungry or tired or sick. She never made excuses.

“Knowing that she lived in a car and still managed to come through like she has year after year, semester after semester — I’m still blown away by her dedication,” Albertson said. “I have young students who complain because they have to get out of their warm beds to come to class, and when they’re in the newsroom, they complain. Beatrice has designed our publications in air conditioned malls to escape from the 110 degree temperatures in her car. She has pride and respect for herself and her work. I couldn’t live this way. I don’t have the strength.”

Brigette Lugo, former editor-in-chief of Substance Magazine and current editor-in-chief of Substance.Media, worked alongside Beatrice on the magazine staff. She and Beatrice have known each other since she first joined the journalism program.

“We had a connection from the beginning. She always had a nickname for me: ‘Frida,’ after the Mexican painter I love. We could joke and talk and laugh as friends, but as colleagues, I would learn so much from her talent in design.

I was always in awe of her attention to detail.”

Lugo said that after learning of Beatrice’s struggles, she was heartbroken.

“I felt that if ever complained about my own young life, I was selfish. Here is this woman living out of her car and laying out full magazine issues and I can’t even turn in a math assignment from my comfy room,” Lugo said.

Lugo added that Beatrice changed the way she approaches life.

“Because of her I take nothing for granted,” Lugo said. “I consider her someone who will always have a significant place in my heart.”

Thanks to Beatrice, the student newspaper and student magazine has won more awards than Albertson can count, including the highest awards of General Excellence, Best Newspaper Design, Best Magazine Design, and first place awards for design and visuals all from major academic media organizations like the Associated Collegiate Press, College Media Association, California College Media Association, the Journalism Association of Community Colleges, and even a professional industry Maggie Award for Best College Magazine.

“Beatrice is a superstar. She should be working at a top magazine or news organization, not struggling to get by,” Albertson said.

In the last 10 years, Albertson has exhausted every resource available to her to help Beatrice. She rallied her colleagues at Mt. SAC to help pay for a monthly rented room for Beatrice, but that was only temporary. She hired an ancestry professional to locate Beatrice’s father’s birth certificate as he, too, was born in the United States. And they did. But even a copy of his birth certificate didn’t change much because there is no DNA or living relatives to tie Beatrice to the man on the birth certificate. Albertson hired an immigration attorney to review Beatrice’s case, but he was unqualified to help. Then, she consulted an international lawyer who told her that it would cost tens of thousands of dollars to help someone like Beatrice. Ironically, if she had been born in Mexico, the lawyers said it would be simpler to get her citizenship.

The lawyer said that Beatrice’s case was one of the most challenging because she is a “woman without a country.”

“I know she’s really trying really hard to survive,” Valenzuela said. “That’s her situation — surviving. I know there’s avenues she could take, but seems like it’s really difficult because there’s all these opportunities that we’re all promised, you know, by our government, but they don’t put us all in the same category or in the same point at the starting line.”

To this day, only a handful of people know about Beatrice’s circumstances. She doesn’t want people to pity her. She doesn’t want a handout. She wants to be known for her abilities and her contributions, and she knows that her homelessness will be the lens through which people see her.

In 2013 at age 52, the decades of poor living conditions and cheap food took a toll on Beatrice’s health. Her legs swelled and scabbed, making it nearly impossible to walk. Albertson’s husband, a physician, was able to get her some blood tests and have her examined by a colleague. She was diagnosed with diabetes. It was so severe, doctors weren’t sure how much longer she had to live. Beatrice was indifferent.

“If I explode, I explode,” she said. “At this point, if I die, it will be mercy. All my pain will be gone,” she said.

That December, while laying in her car one night listening to the radio, a piece of Beatrice’s faith was restored. The hopeful voice of a minister hummed through the car speakers. She listened intently as he preached about the healing promises of God. This was not Beatrice’s first exposure to religion. She grew up in a strict Catholic home, but each insurmountable hardship diminished her faith, little by little. For Beatrice, this sermon was anything but coincidence. Tears streamed down her face as she began to believe again, trusting that God would heal her.

Although she couldn’t afford treatment or medicine to help her ailments, she clung to her faith. She stopped drinking sugary drinks and tried to eat better. As time passed, her symptoms began to improve. When she went back to the doctor, she was told that there were no signs that she had diabetes. She believed it was a miracle from God.

Other things began to fall into place as well. Soon after she began attending a local church, a family called in looking for an in-home care attendant for a sick family member. The church recommended Beatrice.

Since October, Beatrice has lived with Rosanne, 60, preparing all her meals, doing laundry, keeping the house clean, accompanying her to doctor’s appointments, grocery shopping, and running errands.

Beatrice is grateful for a roof over her head, a bed to sleep in, and an income, but she has been told by the family that this is only temporary. When her time with Roseanne is up, she will be back where she started — living in her car. Although she has endured too much to be optimistic of her future, she clings to a sliver of hope that lingers from her youth and the promise of her faith that God will provide.

Albertson hopes that someone will come across her story and be able to help.

“I can’t think of anyone who deserves to be a productive member of the United States more than Beatrice,” Albertson said. “I hope every day that someone will see the potential in this woman and help her gain citizenship.”

Despite a lifetime of denials and rejections, Beatrice simply wants an opportunity to work hard and to make something of her life. Even now, it would mean that five decades of struggle and sacrifice weren’t for nothing.

“All I want is to leave my mark on the world,” she said.

Jessica Fuller served as the managing editor of the Mountaineer Student Newspaper and editor-in-chief of Substance Magazine before transferring to Cal State Fullerton where she received a bachelor’s degree in communication, and then a master’s degree in education from Azusa Pacific University. She now works as a project coordinator for the journalism program, and a counselor at Mt. San Antonio College.

Albert Serna served as the editor-in- chief of SAC.Media and editor-in-chief of Substance Magazine before transferring to San Francisco State where he is majoring in journalism. His work has been featured in numerous publications including the Huffington Post.

Adolfo Tigerino is the former editor-in-chief of Mountiewire, and currently attends Cal State Fullerton where he is majoring in journalism.

Rich Asher Yap is the former editor-in-chief of Substance Magazine and a graduate of UCLA. He is an award winning filmmaker, actor, and performance artist.