For Santa Ana, Rent Control is Long Overdue

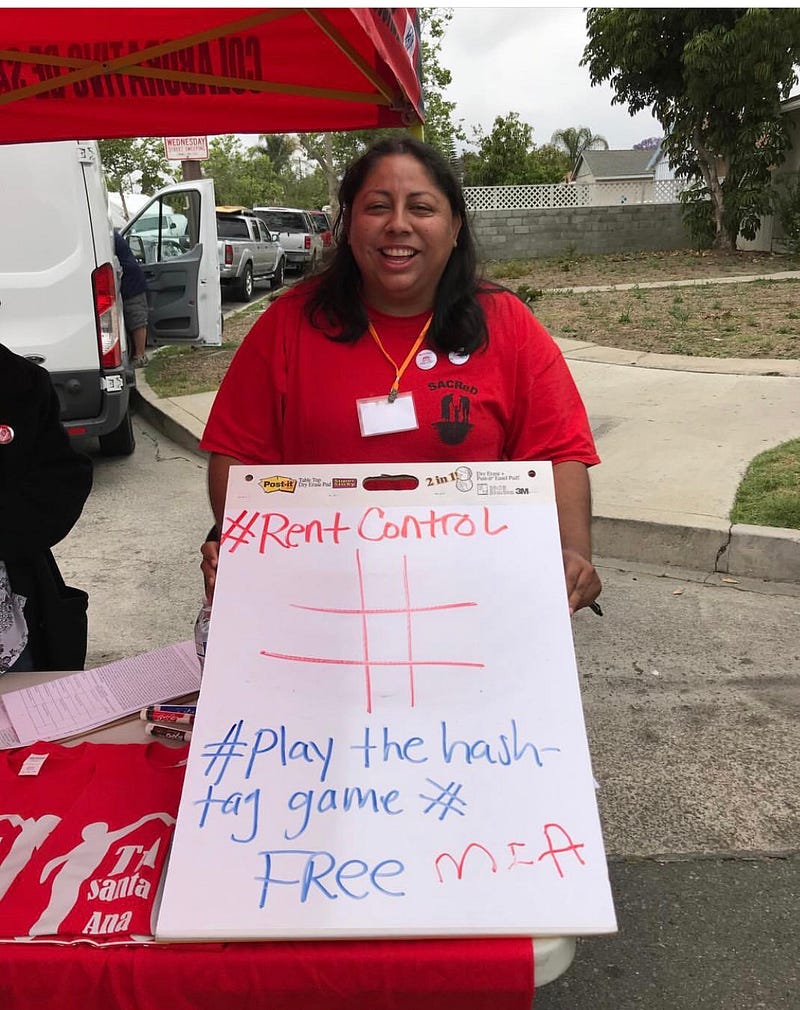

Armed with clipboards and pens, these Santaneras are fighting to stay in the city they love.

Idalia Rios points to the building she’s lived in for the last nine years. “If rent control happens, then I can stay and my kids can have, I wouldn’t say a better life, but they can still keep the life that they have.”

She lives in the Lacy neighborhood of Santa Ana, an area where many immigrant families and their children reside. In a 2016 report called “Lacy in Crisis and in Action,” one out of four respondents lived on month-to-month leases, and 31 percent had no contract at all.

The Lacy neighborhood is also home to Vecindario Lacy en Accion (Ve.L.A.), a group of residents who, according to their Facebook page, “share the vision of improving the quality of life in their neighborhood and the city of Santa Ana.” They facilitate community workshops, distribute toys and food, and were one of the groups who advocated for Santa Ana to create a legal defense fund for immigrants. Rios has been involved in Ve.L.A. for the last year, and she’s been able to connect and be part of a mutually supportive community of families.

As Rios describes her community, a woman walking with her children waves and asks when Rios will be going home. “I just need to pick up my children, and then I’ll head over,” she responds to them in Spanish.

Being a single mother, Rios feels it is important to be able to rely on her friends to support her and her children, and in return, she does the same for them. “If I’m not able to pick them up, then I can count on one of my neighbors to.”

However, last month Rios was hit with a 200 dollar rent increase. Mextli Lopez, a volunteer for Tenants United Santa Ana (Tú Santa Ana), a coalition of organizations and Santa Ana residents who have come together to get legal protections for renters, says this is far from an anomaly.

“Landlords are raising rent by 200 dollars, 300 dollars, 400 dollars- that’s completely unreasonable, especially if you’re working class and living under the poverty line,” says Lopez.

In fact, at a Feb. 6 city council meeting, the city’s housing division manager Judson Brown highlighted that in comparison to other cities within Orange County, Santa Ana has the highest percent of residents living in poverty at 22.1 percent. According to a 2016 American Community Survey, Santa Ana is 56 percent renter occupied. This has lead to Tú Santa Ana‘s current mission: they need to gather a minimum of 9,854 signatures to get rent control on the ballot by November 2018.

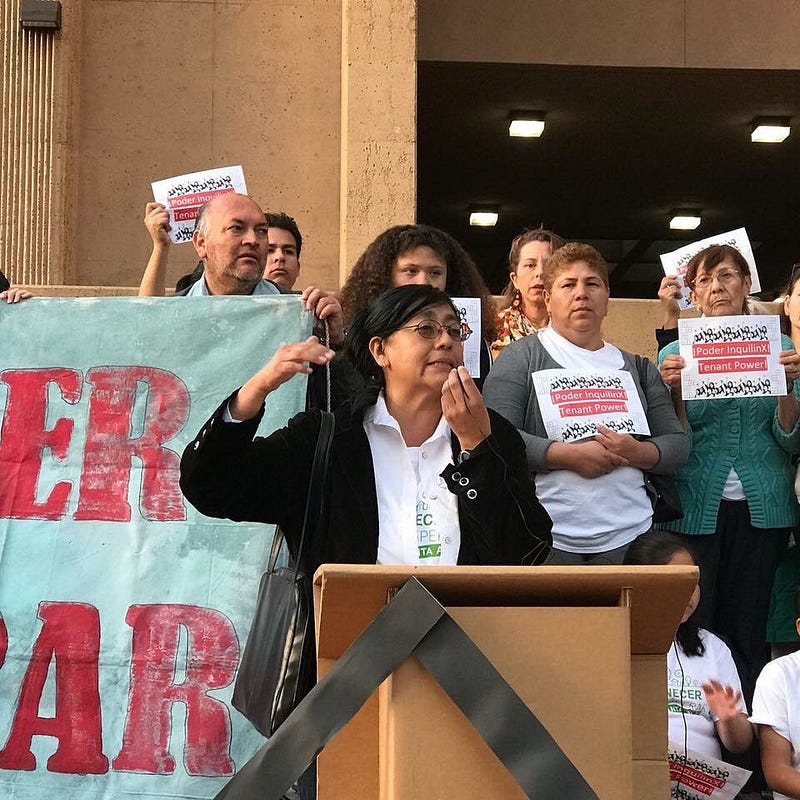

Karla Juarez is one of three proponents, someone who formally puts forward a legal proposal. In this case, she has put forward the “City of Santa Ana Rent Stabilization and Renters’ Rights Act” ordinance.

“We are trying to protect the families in Santa Ana, so they don’t get displaced,” Juarez says firmly.

If successful, the ordinance would put forth the following regulations:

- Rent can be increased a maximum of once per year.

- A rent increase has to be based on the increase in the Consumer Price Index (a monthly measurement of U.S. prices for most household goods and services) for the Anaheim-Santa Ana-Irvine region.

- A seven member Santa Ana Rent Board would be established to manage this ordinance.

But these regulations won’t be applied to all renters.

The Costa Hawkins Rental Housing Act of 1995, a sinister California state law, prevents cities from applying rent control to properties built after Feb. 1, 1995, as well as single family residences, such as houses and condominiums. While the proposed ordinance is still in observance of this law, 67 percent of housing units in Santa Ana are still eligible for rent control.

“Costa Hawkins is one of the biggest mountains that we have to walk over,” Juarez said. “We are also fighting to repeal Costa Hawkins.” This fight is statewide, with activists from Oakland to Los Angeles working to repeal it and introduce the Affordable Housing Act on the ballot by November 2018.

Because Juarez has lived in Santa Ana for 30 years, she has seen the effects of gentrification sweep across Calle Cuatro (now known as Downtown Santa Ana) and bleed out into the neighborhoods and areas surrounding it.

She noticed it when the city chopped the palm trees down in Calle Cuatro about 15 years ago. Then she saw the streets starting to be cleaned more often. At the time, Juarez was hopeful for change, but she didn’t know that these seemingly benign actions would exacerbate the already dire housing situation in Santa Ana.

As she describes the expensive new buildings popping up throughout Santa Ana, Juarez questions, “Who are they building these places for? It’s definitely not us. If it’s not us, where do we fit into this community?”

“There is this overwhelming belief that the city needs to be cleaned up- and by “clean up,” they mean to get rid of folks of color,” Mextli Lopez says. She believes that property owners raise their rents when they see new people, who tend to be middle class, upper-middle class, and or white, move to Santa Ana.

Silvia Hernandez, a volunteer for Tu Santa Ana, is coming head to head with Lopez’s words. She has been in a legal battle with the person who recently purchased the house she’s been renting for the last 17 years. Her former landlord sold the property without telling her, and the new owner gave her two months to move out. But after only one and a half months, he tried to force her to leave immediately. He cut off her gas, electricity, and water, and he threatened to call ICE on everyone who lives there.

“In Santa Ana, I can do whatever I want,” he once told her. But she is proving him wrong.

The Latino Health Access organization in Santa Ana connected Hernandez to the Public Law Center, where she was able to procure an attorney who has been representing and advocating for her in court. As it turns out, her landlord was breaking a new law. The law, AB 291, prohibits landlords from threatening to report tenants to ICE. Although this is the age of information, this information is not reaching communities of color. And since this law was recently passed, not many people know about it.

“How can this truly be a sanctuary city, where most of us are immigrants and are renters, but we can’t afford to live here?” Lopez asked.

As the movement continues, this question will be on the minds of these Santaneras as they knock on door after door to ask for signatures. If you are a Santa Ana resident and citizen of the United States, you can sign to get rent control on your ballot. Opportunities to sign the petition will be at Latino Health Access Mon. through Fri. at 450 W. 4th St. and at SACReD on Saturdays and Sundays at 837 N. Ross St. You can also follow the coalition on Instagram @Tenants_United_Santa_Ana.