Daddy’s little festering wound

My secret struggle as a CSA survivor

Content Warning: Content deals with sexual assault and childhood sexual abuse.

I don’t really remember much about it. I don’t really remember much of my childhood actually. I remember small things, like sink baths and holding my little brother’s hand as we crossed the street. I remember the small apartment we moved into after he left us. I remember sitting in my mother’s lap in her big plush rocking chair, as she smoothed my hair and read me story after story in her broken English. I remember the way his breath smelled, warm and sour, when he raped me.

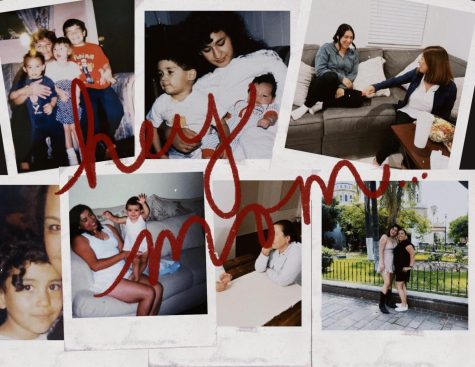

I know my father through photographs and snippets of overheard stories. He was a tall man with short-cropped hair and a wide smile. He loved taking photos. He was hardly seen without a camera, determined to document his happy family. My mother has album after album tucked away, with their yellowing pages adorned with everything from birthdays to mall trips. They start with photos of my mother, her smile bright and nervous as she poses in the hallway of their apartment. There’s a few photos of them sprinkled in: my father holding her face in his hands as he kisses her, my mother sitting in his lap as they laugh together, the two of them holding hands in the snow, barely recognizable in their huge winter coats. There are photos of her swollen 22-year-old belly, heavy with the weight of me growing inside. There are photos of me through the years, with wild black hair and shining eyes, the blinding earnestness of a little girl smiling at her father behind the lens.

He was a boisterous man, who was quick to make friends and laughed loudly without shame. He was vain and proud, particular about his appearance, never seen without a fresh haircut or wrinkled clothing. There are photos of him in the albums too, in his signature pose. Legs together, arms open and outstretched. My memories of him are poor, foggy around the edges and pitch black in places. I have a general memory of my early childhood being happy. We were poor but they made sure I never wanted. I remember being loved and cared for. I remember my father as kind and gentle, always with the energy to run around and play regardless of how late he came home. He was very affectionate, always pulling me into his lap or pressing a kiss to my skin.

My parents separated soon after my first brother was born, and my mother got custody of us. I was 8 years old. We saw him on weekends and I would wait outside with my little suitcase next to me on the sidewalk hours before the time he said he would be there despite my mother’s protests. He was always late of course, but it didn’t matter. He was my hero, my bright peppercorn eyes only seeing the man he presented and not the man he was. But I would soon learn what my mother already knew — there was a different man underneath the sparkling smile and the freshly ironed clothes.

I couldn’t tell you the number of weekends I saw him, but I could tell you the places he lived. There was the trailer in the desert, surrounded by yucca palms with ducklings in the bathtub (he was raising them to sell.) There was his slew of rented rooms, in suburb and cities. In farmhouses and apartments. I remember when he finally had his own place, an apartment not too far from my mother’s. I remember it was an apartment complex, a real one with a leasing office and a pool and everything. I was so happy. His own apartment meant more sleepovers, his own apartment meant I would have clothes and toys there instead of lugging it over each time, a refugee seeking asylum. His own apartment meant that we were alone.

I am the shape you made me. Filth teaches filth.

— Sophokles

The memory itself is hazy, the act of my abuse, the number of times — it all pales in comparison to the small trite details that haunt me to this day. The stink of his cologne, mixed with the stench of his sweaty flesh. The fluttering of my hummingbird heart, confused by how much it hurt when he was so careful, so gentle. I remember telling myself to be patient, that this was just like the dentist, just like getting shots. That this was some strange adult thing that would make sense later. I just had to be good and maybe I would even get a treat for being so patient, so understanding. I remember the texture of the wall and picturing flora and fauna on its mountain-like ranges. I remember the popcorn ceiling. I remember the blood, cherry bright against the cream of his bedding. I remember no treat, only a secret I would keep for almost a decade, and a cancer that would spread with time.

The next time I saw him, after the incident, I remember solemnly pulling him aside, and reprimanding him in my own way. Choosing my words carefully so as to not hurt his feelings, I remember telling him I didn’t think we were supposed to do things like that. I remember asking him to never do it again. To his credit, and my recollection, it was the first and final time. But then again, the merit of both is lacking.

It took me a long time to figure out what happened to me, a long time to weave together meaning from the tattering strings of my memory. I cried more often afterward, tears becoming my knee-jerk reaction to any extreme emotion I felt. They flowed so freely and wildly at times that it frightened my child brain, thinking surely the day will come when my tears will rob me of all my being and I’ll evaporate. Like a ghost. Like a dream.

I felt this sadness inside of me, a weight plunging through my sails, dragging me to unknowable depths. I felt empty, a hollowness that ran beneath all of my days. There was anger too, but that came later. While I was figuring out what really happened to me, my mother and I both assumed that the ache, the sadness, the pain was because he had left. Without my father, I lost her too. She had to work so much and for so long that she spent less time with us. My babysitter now sat in the big plush rocking chair to read me, and at night I could sometimes hear my mother cry. My mother has always been reserved, her strength hewn by years in a country that cares not for her. Her soft hands calloused by years of blue-collar jobs, her laugh lines gave way to etchings of a worried forehead, her Spanish saved for the safety of our home. In this life, hardship is a consequence of existence, she would say in hushed tones. In Mexico, these things are known. She came here at 18, too old to marry the rancheros at home.

I need a father, I need a mother, I need some older, wiser being to cry to. I talk to God but the sky is empty. — Sylvia Plath

Once I learned how to read, I would abandon my younger brother for my books, leaving him to fend for himself. I spent my childhood reading book after book, escaping my confusing reality the only way I knew how. In books, the fathers were kind and loving. In books, the girls were brave and strong. In books, things happened the way they were supposed to. I traced the lettering on their spines and wished for strength. Wished for something, anything, to ball up this hurt and toss it away as easily as a paper ball in a wastebasket. I wished for it to stop. Which, in turn, would morph into an ache to die. I was not a child that played anymore. Though my wide eyes and braided hair betrayed me, I was no longer a little girl. I was something new, red-faced and thrashing. A skinned knee so raw that the pulpy cords of scarlet shone through the flesh.

I kept my secret for years, stubbornly thinking that I could exchange time for catharsis. My mother remarried, after a few years of being courted persistently by a man at work. He was also divorced with two children from his first marriage, two boys in the custody of their mother. I always thought of him like a junkyard dog, hardened by outside forces like the deep-rooted machismo of Mexican culture. My stepfather was a terrible alcoholic. My mother slept with a bat under her bed until she threatened to leave him unless he got sober. He quit cold turkey and my mother has stood by him, for better or worse. I despised him. He took up smoking during his sobriety, the pungent fumes of Marlboro Reds seeping into my mother’s big plush rocking chair as he spat out puff after puff on the patio.

I thought he was crass, and beneath my mother. He disliked me for not respecting him as the new man of the house and for being a little know-it-all. I did not accept him for a very long time, and we butted heads for years. My younger brother was small enough not to remember our birth father, growing up with our stepfather as his sole parental figure. As the years went on, my mother and stepfather had children of their own. And although my stepfather was always “hoping for a daughter,” they had boy after boy after boy, heightening his resentment towards me.

My mother protected me as much as she could, but I never told her how much he would hurt me. I wanted her to be happy, and I knew that despite everything, he really loved her and, for the most part, he was a good father to my brothers. It was me who was the issue. I knew that she would not always step between us for the sake of her marriage and I was not her only child. She could not always be there for me. She had already sacrificed so much, worked so hard, gave me the world. It was because of my duty to her and my brothers that I just kinda took whatever he dished out. I knew in my heart that if it came down to it, she would pick me every time. And that was enough to give me strength when he was at his most cruel.

He used to constantly berate me and put me down, exasperated by my strange interests and behavior. He’s the kind of father that would get angry with us for spilling something on accident, his nostrils flaring and voice rising as he scolded us. I, of course, received a disproportionate amount of his anger, judgment, and disgust. As I got older and my depression worsened, I could do nothing right by him. I did not take pride in my appearance as my mother did, she never left the house without looking put together. I wore a lot of black and baggy clothing, my hair frizzy and unkempt. He had a hair-trigger and a mean streak. He wasn’t always fire and brimstone, sometimes he would just mutter insults under his breath. His favorite thing was to call me stupid, doing so for years until finally one morning I had enough.

He was taking me to school and we were about to leave when I had to run back upstairs to grab my homework. I came back down and he muttered, “God, I can’t believe how you can be so fucking stupid sometimes,” and I snapped. Years of biting my tongue and letting him bark had gotten to me. I screamed at him to stop, to never call me that again, that it hurt me more each time. I begged with him to treat me with the respect a parent owes their child. I pleaded with him to be my dad, to act as a father to me. To protect me from pain and stop being the one who caused it. To love me a fucking little. I burst into tears, frightened of the terrible anger I was sure I had awakened in him. To my surprise, he was quiet. He apologized and promised he would never do it again. He looked, for a moment, like a scolded child, and the guilt and shame that I carried with me constantly touched his heart. I could see it in his face too. To this day he has kept his promise.

He has gotten better, mellowed by age, the high blood pressure his rage and alcoholism developed, and by my youngest brother, whose strange interests and behavior mirrors my own in many ways. He’s still rough around the edges, of course, nobody is perfect. My mother keeps his temper in check, telling him to calm down if he starts yelling or getting angry like he used to. We have had our issues, but he is the person who volunteered for my marching band competitions when my director made parental involvement mandatory. He worked two full-time jobs to support us. He bought me my first car. However dysfunctional or imperfect, he is my sole parental figure.

Not only was I going through the normal amount of crippling self-loathing, a developing understanding of my womanhood, and coping with my parent’s divorce but I also had the fun twist of a deep primal wound that had direct ties to the way I perceived love, formed relationships and viewed sexuality. Suffice to say, puberty was the fucking worst. I went through middle school and started high school soaked in shame, practicing martyrdom and self-flagellation. I was neurotic to a fault and anxious to no end. I struggled with my sexuality, both hormonal and in orientation. I knew what stereotypes followed childhood sexual abuse survivors, how we were damaged goods, and doomed to a life of hypersexuality. That possibility frightened me to no end. I hated the idea of something beyond my control affecting me in that way. Lack of control over my future and lack of control, in general, continue to be my greatest fears.

I WANTED TO BE LOVED SO DESPERATELY THAT MY FINGERS SHOOK WITH IT I AM NOT BEAUTIFUL BUT I COULD BE — Emily Palermo.

I felt guilt and shame over my trauma, and the ways it was making me feel. I felt guilty for wanting to die when my parents worked so hard to support us, three full-time jobs between both of them, my stepfather having two and my mother the one. I was ashamed for feeling depressed and suicidal because my mother was always telling us how lucky we were to have been born in America, that we had so much opportunity. I kept shaking myself, wondering which one of my little brothers would find my body. How much hurt would that cause? How much trauma? As little as I valued my own life, I had a family who cared very much for me.

This is where the anger came in. This is where I was angry it had even happened to me at all. This is where I was furious my father betrayed me so profoundly. This is where I was fucking pissed at how it continued to affect my life. I saw its inky black tendrils still swirled around me and denied it out of spite. I was going to live, goddamnit.

I rode out waves of depression with the grim white-knuckled determination of a man at war, seeing things through to the bitter end. I spent manic episodes inhaling books at a frightening speed that I have not been able to replicate since — 500 plus page novels in a single sitting. I watched a lot of late-night TV, a lot of pop culture mashups like the “I Love the [insert decade here]” series from VH1. I watched a lot of movies and developed a love for cinema, the horror genre in particular. I listened to my small collection of alternative rock CDs over and over, until the lyrics were burned into my brain. I did everything I could to distract myself from the gnawing ache inside of me.

I was in my high school’s marching band and yearbook. I was the co-president of the Pride club. I had a group of friends I enjoyed spending time with. I had a loving, supportive family in my mother and younger brothers. I found solace and peace in quality time with others and catharsis in responsibility. If I could find reasons to be valued, expectations I could meet, it would lower the voice telling me it was all for naught, that I was an apple with a soggy rotten core and eventually everyone will see that I’m no good.

It continues to be a daily struggle to go through the machinations of life with my trauma constantly pressing its ghostly face against the glass. I still have my extreme highs and lows, some days I feel like I am on the precipice of greatness and some days I feel like I’m on the brink of failure. I’m still an easy cry (a snotty, hiccupy cry at that,) tears streaming down my face whenever I experience an extreme emotion, be it sadness, anger or happiness.

I developed a heightened sense of awareness due to my years of abuse. I notice every little detail. A change of pitch in a voice, the shift of body weight, a simple glance was often the only warning sign to get the hell out of dodge. I know when someone is about to hurt me. I know when someone has the ability to hurt. Sometimes they’re like my stepfather, someone with a hair-trigger and a bloated sense of entitlement. Sometimes they’re like my birth father, someone whose voice is syrupy sweet but dripping with darker intention. I know when someone is hurting. I often see my ghost in others, so many of us are haunted in our own ways.

This, in turn, has lead to me being extremely empathetic. It’s easy to feel the pain of others when you’re a walking nerve yourself. I have dedicated myself to constantly strive to be understanding and respectful of others. As negative and cynical I used to be, I have always had a profound love for humanity, and believe highly in the intrinsic value of life. I try very hard to extend kindness and compassion to those around me. It’s the reason why I became a writer — to better communicate with others. To explore humanity and champion the causes of the disenfranchised. I speak up for others, attempting to shield them the way that I wished someone had for me. I can’t help but volunteer my cheek to take a punch if it means someone else is saved from the bite of a fist. I can’t help but want to protect and nurture. I can’t shut up if someone is being treated unfairly, taken advantage of, or straight up in danger. I have long since learned I cannot rely on the kindness of others. I can only rely on the kindness of myself.

so of course I’m a kid who is always looking for people that I can connect with profoundly. I’m willing to take the risk after you … You get kicked around enough, two things, you either withdraw totally, or you say well, “I could take another kick.” — Junot Diaz

I have seen the cruelty of man and I have felt the bite of its kiss. I know what it’s like to be hurt by someone. I know what it’s like to hurt. I could give a fucking Ted Talk on hurt. And I don’t want to put any more of that into the world. I try so hard to support those around me. I don’t want anyone to feel how I have felt. I want to go on national television and tell everyone, “Look, I have felt enough sadness, loneliness, shame and guilt for all of us. There is no need to behave this way with each other.”

A heart that always understands also gets tired. I am still trying to find the balance. Often times I give so much of myself I have nothing left. You get tired of being a lightning rod. You get tired of trying to advocate in a world that feels like there is nothing other than greed, pain and suffering. There are days I retreat into myself. There are days where the fog of my own pain is too thick.

To this day, I have not been fortunate enough to speak to a professional. Therapy is a luxury, and although I am grateful to have free health insurance through the state of California, I have not been able to find someone who takes it and would be able to help me both with my trauma and my gender dysphoria. I feel like I still have made progress. I have a healthy relationship with my sexuality, both hormonal and orientation. I have come out as a queer nonbinary person to everyone except my family, who I fear would not understand, not yet. I take pride in my academic success, my recognition as a writer and journalist, my position as editor-in-chief of this publication. I have friends who love and cherish me, whose support and understanding have gotten me through many a difficult night.

I feel like I have gotten better.

Or maybe I’m just better at hiding it.

I am

a series of

small victories

and large defeats

and I am as

amazed

as any other

that

I have gotten

from there to

here — Chuck Bukowski