How Bill Maher Wronged Tunisia

Inaccurate generalizations stigmatize a country on the forefront of Middle Eastern democracy

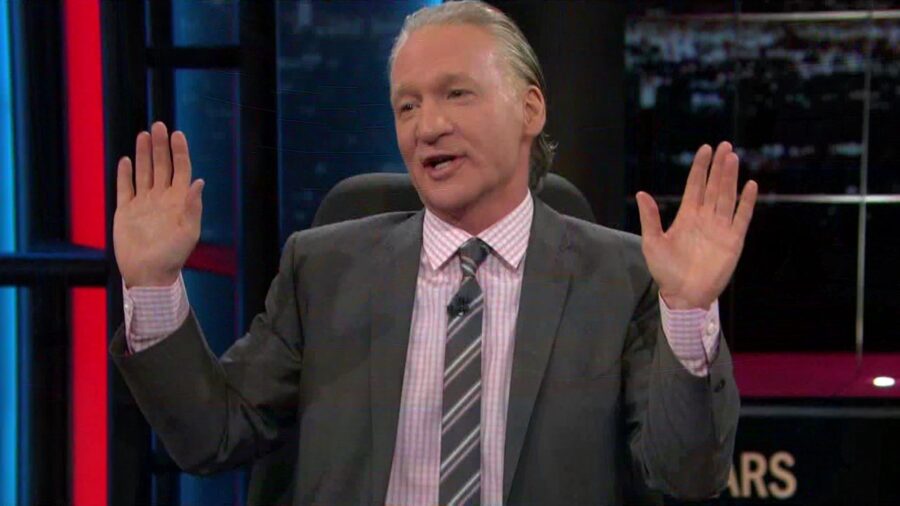

Comedian Bill Maher faced fiery criticism early in October after a heated conversation about Islam with actor Ben Affleck went viral. On Oct. 24, Maher’s conversation on Islam continued with Dr. Cornel West and eventually referenced Tunisia, the North African country best known in the West for sparking the wave of pro-democracy protests known as the “Arab Spring” which swept through much of the region in 2011.

Most Americans are unfamiliar with Tunisia, particularly the complexities of its transition to democracy, including socio-economic and political struggles. So, in the few rare instances that Tunisia is brought to the attention of Americans, it is imperative that it not be presented incorrectly. But that is exactly what Maher did. He chose to make a mention of Tunisia in a way that would, for many, incorrectly solidify what Tunisia is all about.

The importance of correcting Maher on an issue as seemingly insignificant as his reference to a fairly unknown North African country rests in its greater implications. Shows like Real Time with Bill Maher have the potential to shape the beliefs of their viewers, and by extension, the greater public. It should go without saying, then, why this particular instance is problematic.

The conversation on Maher’s Oct. 24 show veered into Islam with Maher contending that Islam is a religion that is inherently not peaceful because the majority of its followers – Muslims – expose themselves to violent beliefs. Tunisia became the case in point when Maher used a New York Times article by David K. Kirkpatrick on ISIS supporters in Tunisia to back his reasoning. Whether you agree with Maher’s general contentions on Islam is irrelevant; it is important to know why his use of Tunisia for that case is unfounded.

He cites the New York Times article, saying:

“No other country has sent more fighters to ISIS than Tunisia even though they’re the most educated and cosmopolitan in the Middle East. And they talked to all these people in the cafés there in Tunisia and even the ones who weren’t going to join ISIS were big fans. Big fans.”

Tunisians being “big fans” of ISIS while also being considered the region’s “most educated and cosmopolitan” was to show that even Muslims who are seemingly liberal still accept violent ideas. Ergo, Islam itself is the problem – a rather convenient point for Maher.

But is that what the article says?

Kirkpatrick says quite revealingly mid-way that “…only a minority of Tunisians have expressed support for the militants.” It is, therefore, a hasty generalization to use the “minority” of Tunisians who support ISIS in the case for Islam being inherently violent.

The select interviewees in one suburb of the capital city are hardly representative of the greater capital, let alone 11 million Tunisians, and much less the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims.

But even if we consider the interviewees’ unrepresentative inclinations towards ISIS, there’s still a problem with Maher’s use of it for his discussions against Islam. The men interviewed cited mainly socio-economic and political reasons for being supportive of ISIS, not religious ones.

Here are some quotes from different individuals in the article:

“The Islamic State is a true caliphate, a system that is fair and just, where you don’t have to follow somebody’s orders because he is rich or powerful.”

“It is the only way to give the people back their true rights, by giving the natural resources back to the people.”

“I said: ‘Are there some pretty girls? Maybe I will go there and settle down.’ ”

Maher jokes about Tunisians’ inclination towards ISIS – i.e. violence – as the obvious case of Islam and violence being connected. But Kirkpatrick notes that “almost no one” he spoke to believed the news reports about the ISIS atrocities. Of the news reports, one man said, “It is made up. All of this is manufactured in the West.”

There’s the crux.

If the Tunisians interviewed do not believe the news about ISIS’s atrocities but instead believe it is providing a “fair and just” lifestyle for people, why wouldn’t they be “big fans?” The point here is less about these individuals’ ignorance of ISIS violence and more about them being a poor example of proof that Islam is a violent religion for even “educated and cosmopolitan” people like Tunisians. If these men do not accept ISIS’s brutalities to be true, how can they be accused of a penchant for violence, as Maher interprets?

Millions of peaceful Tunisians who identify as being Muslim live behind Maher’s generalizations and assumptions. It is possible that some of Maher’s own fans believe them as well. And it isn’t fair to Tunisia. It is the country where a young man’s self-immolation led to a revolution in 2011 that culminated in toppling a dictator and began the arduous road to democracy.

In January of this year, Tunisians passed a new constitution that grants freedom of religion and calls for equality for women in the elected Assemblies, among other liberal policies. Their constitution was internationally lauded as a triumph for being noticeably progressive and reflecting a long-fought battle for consensus from all sides, from moderate Islamists to secularists. In fact, just last week, Tunisians voted in legislative elections that gave a secular party the most seats in its Assembly.

Unfortunately, for those viewers whose only understanding of Tunisia comes through Maher’s skewed portrayal, none of these achievements will be known. When watching a television talent like Bill Maher, it’s crucial to think critically behind the seemingly convincing arguments being made. He presented a country (Tunisia) and its people (Tunisians) unjustly for the sake of his wider argument on Islam, using unrepresentative facts taken from an article he failed, purposely or otherwise, to accurately interpret.

Kiran Alvi is a freelance journalist living in Tunisia. She is a graduate of Mt. San Antonio College where she served on the speech team and as managing editor of the Mountaineer student newspaper. She received a bachelor’s in journalism from USC Annenberg and graduated with a masters degree from the Columbia Graduate School for Journalism. She has worked as a media researcher with NPR, a broadcast news intern at Al Jazeera, a TV news reporter with Nile TV in Cairo, a beat reporter with the BronxInk.com and is co-producer of the Kickstarter funded documentary, Queens.

This story is a part of a special alumni series. Students who have graduated or transferred from Mt. San Antonio’s journalism program are featured weekly.

Substance is a publication of the Mt. San Antonio College Journalism Program. The program recently moved its newsroom over to Medium as part of a one-year experiment. Read about it here.