Rape, Violence, Assault and a Culture That Excuses It All

Rape culture is our culture

Story by Jennifer Sandy and Albert Serna

Jessica Milner was raped when she was 17 by someone she knew — someone she trusted and considered a friend. Now at 23, she recounts the story and how the aftermath changed the person she was, first for the worse, and then for the better.

It was a week before Milner’s graduation from high school in Los Angeles , California and her 18th birthday. There was a party being thrown by Milner’s male friend, whose parents were out of town. At the party, alcohol was served, and Milner said everyone had been drinking.

“Everyone was in his room and we were just looking at yearbooks and talking about stuff,” Milner said. “Slowly, people left, and that’s when he started to kiss me. I did think he was attractive, so it was okay. We were making out and he fingered me and I was okay. And then he took his dick out and I said ‘No, I don’t want to. I’m not ready.’”

Milner said he was totally calm. He tried pressuring her, like a scene out of a teen movie. Milner told him no, and started to put her pants on. That’s when, according to Milner, things went terribly wrong.

“He put a weight on the door so I couldn’t open it and he stood in my way, so I was like, ‘Move!’ That’s when he pushed me to the ground. He pinned my legs down with his so I couldn’t kick, and he held my arms above my head with his hands. He was a football player, and I wasn’t big, so there was nothing I could do to fight back.”

Milner said he ripped off her underwear and pushed his penis inside her.

“He was saying, ‘Come on! Come on! I know you want it!’ I was crying and screaming because I knew there were people downstairs, and I was hoping someone would hear and come help me. Nobody did.”

No one came — until a latecomer to the party heard her cries for help, broke down the door and pried Milner’s rapist off of her.

Afterward, Milner said she began spiraling out of control. She never told anyone the full story of what happened between her and the host of the party in his bedroom that day, with the exception of a psychiatrist at Riverside Community College. Milner said that she put on a brave face and got through graduation, but immediately following the ceremony, became depressed. That depression didn’t fully release her from its grasp until years later.

“I felt like I was a bad person. I told myself I had been asking for it. We had been making out, so I thought that I was my fault.”

Milner described how her life shifted. She self-medicated with alcohol and partied constantly. She also began to use sex as a weapon.

“I felt disgusting. I felt dirty. I felt used. So, eventually, I discovered a way to make myself feel better— at least for awhile.”

Milner discovered that she could use sex as a means to get men to take her places and buy her things.

“I became not a very nice person. I felt like I had been used, so I started using guys. It didn’t matter to me. That had been taken from me. So, I used sex against them.”

Milner said that every time she went out, her main goal was to find a guy to have sex with because the attention of a guy made her feel as if she was worth something.

Her wake up call came three years after she had been raped. Milner said she had sex with the best friend of a guy she really cared about on the hood of his car, and the hurt in her friend’s eyes when he caught them was enough to make her realize that she had been going down the wrong path.

“It killed me. What made it worse is he drove me home afterward. I had been drinking, of course, and even after I betrayed him like that, he still cared enough to drive me home.”

Milner began to question her behavior over the past three years, and that’s when she came to an important realization. It dawned on her for the first time that her behavior was due to the rape. That night was when she first came to grips with what had happened to her.

“I had something terrible happen to me, and as a result, I did terrible things to others. But that’s the past. The past doesn’t define who I am now.”

The fact that Milner told herself for years after her rape that she was at fault because she had been making out with her rapist is a direct result of the rape culture embedded in everyday American society. Marshall University’s Women’s Center defines rape culture as:

“…an environment in which rape is prevalent and sexual violence against women is normalized and excused in the media and popular culture.”

The website cites victim blaming as part of rape culture. Victim blaming is the belief that a victim of sexual violence did something to invite the attack, or should have done something differently in order to prevent it. Taylor told herself that she asked for it because she was engaging in other sexual activities with her attacker, therefore she had no right to say no to intercourse.

According to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network RAINN, it is estimated that one out of every six women in America has been the victim of either completed or attempted rape. The organization also reports that only three out of every 100 rapists serves time, in part because an average of 60 percent of assaults in the last five years were not reported. There are various reasons for not reporting an assault.

The silence of not reporting rape or sexual assault can lead to an emotional burden on it’s own. For Columbia University Senior Emma Sulkowicz, that burden became her senior thesis. In an article published in Time, Sulkowicz wrote about how she was allegedly raped and the aftermath she encountered as a result. She claims that the incident occurred on the first day of her sophomore year, and that at first she was reluctant to report the incident. It was not until she encountered two other women who had been victimized that she came forward and pressed charges. All three cases, she writes, were dismissed.

“During my hearing, which didn’t take place until seven months after the incident, one panelist kept asking me how it was physically possible for anal rape to happen,” Sulkowicz wrote. She added that it was uncomfortable for her to explain how it happened.

Sulkowicz’s parents, Sandra Leong and Kerry Sulkowicz, wrote an open letter to the university on Oct. 3, regarding what they said has been an inadequate reaction to their daughter’s assault.

“The investigation, hearing, and appeals process that followed her complaint were painfully mishandled. We feel they violated the standards of impartiality, fairness and serious attention to facts of the case,” Leong and Sulkowicz wrote. “We were left with the impression of a university intent on sweeping the issue of rape under the rug.”

Emma Sulkowicz inspired students across the world to join her in carrying their mattresses around on their respective university campuses. The collective carry event was in support of Sulkowicz’s visual arts senior thesis project, in which she’ll carry a mattress everywhere she goes for as long as her alleged rapist attends Columbia. The students involved in the protests have pledged to “carry the weight,” for victims of sexual assault.

A Carry That Weight protest was held on Columbia University’s campus on Oct. 30. Freshman Rowan Hepps Keeney blamed the campus’ administration for being a part of the problem, instead of part of the solution. Keeny told Newsweek, “The administration isn’t really paying attention to what’s important. They’re dancing around the issue, saying it’s not really Columbia’s problem but society in general’s. Though they’re the people who are not expelling the rapists.”

The collective carry was organized by Carrying The Weight Together, a group of Columbia students and alumni who want, according to the group’s site, “to help Emma carry the weight of the physical mattress, give her and other survivors of sexual assault in our community a powerful symbol of our support and solidarity, and show the administration that we stand united in demanding better policies designed to end sexual violence and rape culture on campus.”

Unfortunately, the situation faced by Sulkowicz is not uncommon. One in four college women have been raped, and only 10–25 percent of rapists are expelled. As evidence of rape culture, 40 percent of men who think a date who drinks is more likely to be open to having sex, also think that forcing sex on an intoxicated woman is okay.

There are many reasons why some men tell themselves there are circumstances where it is acceptable to force sex upon a woman, ranging from intoxication to her involvement in the porn industry. One third of all content online is pornography and 88 percent of those scenes contain sexual aggression. With an estimated 2 billion people having searched for pornography online since the beginning of 2014, most of them being men, it is conceivable why some men would assume that having sex with female porn stars is fair game, no matter what the porn star may do to protest.

On Oct. 22, the popular crime television show Law and Order: SVU, featured an episode called “Porn Star’s Requiem.” In the episode quiet, nerdy university student Evie Barnes leads a double life as a porn star. Two of her male classmates discover her secret by stumbling across her videos online, invite her to a party, subsequently rape her and capture the entire attack on video. In the episode, her attackers said that she says “no” in her videos online but she clearly enjoys it, so they had no way to tell the difference when Barnes told them “no” at the party. Much to the dismay of Mariska Hargitay’s character, Olivia Benson, and the rest of her SVU squad, both rapists go free.

These kinds of TV scenarios often mimic reality. Miriam Weeks, better known as Belle Knox, the 19-year-old Duke University student who turned to porn to pay her college tuition, was outed by a Duke University student who watched porn online and recognized her. Knox’s outing made its way through the Greek fraternity system and went viral, resulting in Knox receiving threats of violence and death, as well as harassing messages via social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook, with some individuals endorsing people raping and beating her.

It is no surprise that many females turn to sex work in order to pay for substantial student loans. In fact, Brandon Wade, the founder of Seeking Arrangement, a website that aims to set young college women up with older men in exchange for money, said that his site has over 800,000 members. The porn industry makes a lot of its revenue by selling men the idea that women are property and it is their right to do whatever they please with them whenever they please, and that a “no” is really a “yes” in disguise.

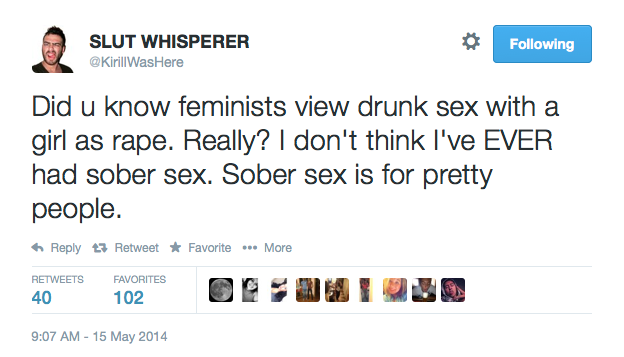

As sobering as a visual of the rape fantasies the porn industry perpetuates, rape culture can be seen running rampant on social media. One Twitter user, @KirillWasHere, known as Slut Whisperer, has openly tweeted about having sex with drunk women, referring to them as sluts.

@KirillWasHere has also tweeted, “You can’t tell me ‘I love getting my hair pulled’ and then be mad at me when I drag you out of the club by your hair.”

In this climate of rape culture, even female children are not safe from online harassment. Creator, writer, producer and actress of the critically acclaimed HBO show Girls, and women’s right’s activist Lena Dunham, recently wrote an autobiography entitled Not That Kind of Girl. The book includes a passage where she describes looking at her younger sister’s vagina to see if it looked like her own, and years later, touching herself while the two shared a bed. Dunham has faced accusations of sexually abusing her sister.

Debby Herbenick, PhD, associate professor at Indiana University, writer for the Kinsey Institute, and author of Sex Made Easy, said that it is normal for young children to explore other children’s bodies, as well as their own.

“Dunham’s story is not one of sexual exploration, and she doesn’t describe any sexual acts. Sex is not a part of it…. People who are attaching sex to these stories seem to equate the genitals with sex, but that’s not how children see their genitals. Dunham’s story is not an uncommon one,” said Herbenick.

The claims that Dunham sexually violated her sister, initially reported by the right-wing news site Truth Revolt, propagate rape culture by lessening the focus on actual violent, sexual crimes. Dunham wrote about an innocent childhood experience, one which experts say is quite common among children, and she has been crucified by the media. It only takes searching #LenaDunham on Twitter to discover that much of the general public has decided that Dunham is no longer worthy of the basic respect human beings are afforded. Meanwhile, it is estimated that only three out of every 100 rapists, people who committed a violent, sexual crime against another person, will ever spend even one day in prison.

Omar Olivarez, a 21-year-old biology major at Mt. San Antonio College, said that these kinds of attitudes need to stop. “That’s one thing our nation, [and] society as a whole needs to go against,” said Olivarez. Olivarez had a similar experience to the one Dunham writes about in her book. When he was four, his six-year-old cousin shared an encounter that some may consider to be sexual. Despite the assertion by peers that this in fact was a form of molestation, Olivarez views it more as a sexual awakening and exploration.

“I like to say I was sexually activated but a lot of people say I was molested as a kid. It was more of an exploration thing. I guess ever since then people have asked me, one of my friends asked me, if that influenced how I am now, and the truth is it did.”

Olivarez added that he is very sexually explicit with his friends in the way that he speaks, and how he jokes. He added that this experience was probably a result of his cousin’s sexual abuse by an uncle. “For him, it was one of his uncles who was molesting him,” said Olivarez.

“Just recently, one of my cousins told me it was one of our uncles and our uncle’s friend that lived in the neighborhood that was molesting him. I guess because that guy started on him, it created a chain reaction.”

Although Olivarez’s cousin was molested as a child, Olivarez insists, like the Dunham sisters, that his experience with his cousin was not one of sexual violation. Victimhood belongs to those who have suffered from an incident that is traumatic or injurious. It is impossible to assign someone the title of “victim,” if that person does not consider themselves one.

Although some extreme media and users of social media have persecuted Dunham for admitting something as innocent as childhood exploration, these media are, perhaps, the driving force in what makes rape and sexual violence normalized and excused. For example, in 2012, feminist, activist, and media critic Anita Sarkeesian questioned women’s representation within video games via the website Feminist Frequency. Subsequently, Sarkeesian received rape and death threats for daring to be a woman questioning an industry dominated by men. Last August, the threats became so frightening that Sarkeesian feared for her safety and left her home due to the fact that someone threatening her told her they had her home address.

“It’s not just boys being boys,” Sarkeesian said. “It’s not just how the internet works. It’s never gonna go away if we ignore it.”

However, Sarkeesian continues to get threatening messages on a daily basis. Instead of being intimidated, Sarkeesian has become a voice for those who have been told that the sexual harassment they have received is somehow their fault. Sarkeesian posts videos, twitter updates and speaks at events about the need for more feminism in the world.

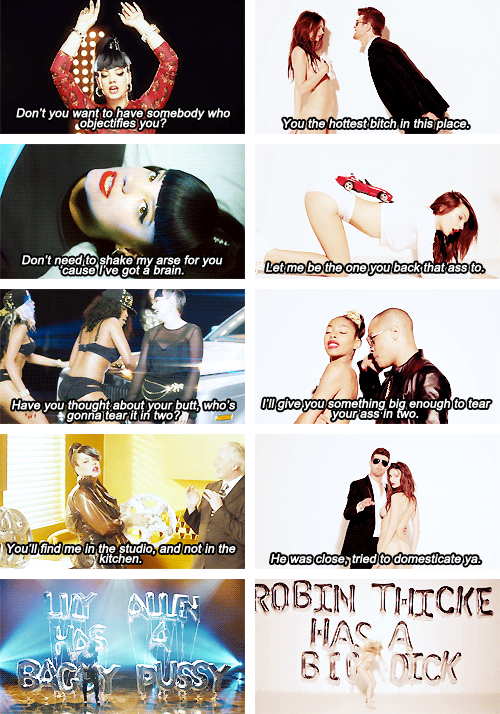

Rape culture can take on many forms; sometimes it is presented as a seemingly harmless, popular song. In 2013 there was major outcry when artist Robin Thicke released his hit song, Blurred Lines. The song, which features lines like “Do it like it hurt, like it hurt, what you don’t like work,” and “I know you want it, but you’re a good girl, the way you grab me, must wanna get nasty.” The Guardian called it “the most controversial song of the decade.”

In response to the video and outcry from the public, British artist Lilly Allen took aim at Thicke with her song “Hard Out Here.” In the video, Allen bashes both Thicke and sexism in the music industry. Thicke did not stay quiet on the subject however; he later claimed that he wrote the song about his wife Paula Patton. “She’s my good girl,” said Thicke. “And I know she wants it because we’ve been together for 20 years.”

Songs like these are far from rare, and rape culture is not only represented in music, but is perpetuated in movies, TV shows and books as well. Among the many TV shows that are guilty of the same thing, the CBS hit comedy Two Broke Girls routinely jokes about rape in a way that trivializes it and makes it seem like a laughing matter.

Anyone who has ever read E.L. James’ wildly popular book 50 Shades of Grey, is familiar with how James disguises rape and rape culture as love. There are many times throughout the trilogy where Ana, the bookish, shy protagonist, does not want to have sex with Christian, her brooding, broken, yet oh-so-sexy “love interest.” Ana makes her objections known, and Christian often ignores her requests and does with her what he pleases. In Ana’s mind, Christian’s acts are justified because he says he loves her, and she usually ends up orgasming in the end. But for victims of sexual assault, their ordeals are anything but funny and the furthest thing from romantic.

Someone’s high school graduation and 18th birthday is typically what marks their official send off into adulthood. Unfortunately for Milner, and people with stories similar to hers, they are forced into adulthood before their time. Instead of celebrating their venture into adulthood by wearing a cap and gown, or blowing out 18 candles on their birthday cake, that memory will forever be tainted with violence, pain, and fear.

Photo illustrations by Adam Ernesto Fuentes and Cynthia Schroeder

*The name of the first source in the source was changed to protect her identity.

Substance is a publication of the Mt. San Antonio College Journalism Program. The program recently moved its newsroom over to Medium as part of a one-year experiment. Read about it here.