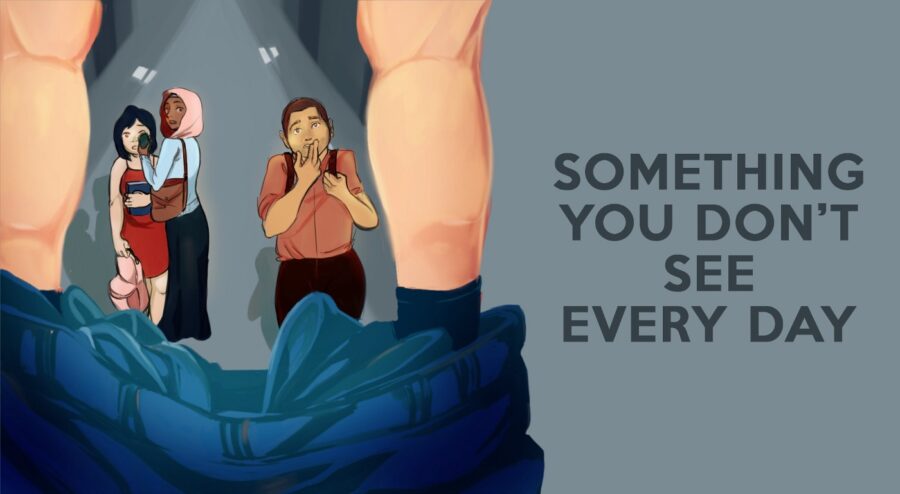

Something You Don’t See Every Day

An unshaven look at how we publicly treat people with disabilities.

I was on a college campus with an individual and he had classes to attend that day. The problem was, he wasn’t in the mood to attend them. I told him that we had to go to class and he would respond, “No! I don’t want to do that. I want to go to the cafeteria!” I told him, “Sorry dude, that’s just not in the cards. That cafeteria you want to go to is on another campus entirely, and you have classes on this campus today.”

We had been going back and fourth with this all morning. At some point, he had had it with not getting his way. So he played his final gambit. He decided to end this cold war with a dirty bomb. To express his displeasure, he dropped his pants in the middle of a packed college campus.

This situation was never covered in the training manual. I frantically searched my memory banks for any training that involved indecent exposure. The pressure was on and the situation was getting hairier by the second.

The penis in question seemed to be looking right at me. I looked around and realized that everyone was looking at me too. Wait, why was everyone looking at me? I wasn’t the one rocking out with my cock out like it was Woodstock circa 1969. After a few back-and-forth motions between a very hairy penis — me — the penis — them — the penis, it suddenly dawned on me: it was my responsibility to deal with this.

As this man’s life coach, I was the mediator between my colleague’s penis and the rest of society.

Let’s start at the beginning. In 2011, I was hired to work with people who have disabilities for a non-profit called Easter Seals. Like most of society, I didn’t know much about people with disabilities. I didn’t really see or interact with them on a daily basis, so my familiarity on this subject was limited. Before applying, I decided to do my homework and search the meaning of “disabled” on the web. First definition I found was from Google stating “(of a person) having a physical or mental condition that limits movements, senses, or activities.”

I remember thinking to myself, If that’s the definition, I’m pretty sure I am disabled. I have anxiety disorder and OCD. Do they let disabled people take care of other disabled people? That’s like letting airline passengers be the plane’s pilot.

As is briefly covered in Google’s definition, having a disability can run the gamut. The Social Security Administration lists all the different conditions that qualify someone as having a disability. Examples like blindness, autism, multiple sclerosis and anxiety disorders are all conditions that qualify someone as having a disability. With conditions as different as the ones listed, it is important to note that disabilities are a scale with many different types of disabilities and needs. Not every person has the same disability, nor will they have the same needs.

After doing the proper research, I decided to apply. A few weeks later, I was hired and given the job title of life coach. My job was to help these individuals navigate their way around the community. I found the job title ironic because I didn’t have a handle on my own life at all, let alone feel confident enough to manage or assist someone else with theirs; but there I was, ready to give it the old college try.

I worked there for two years. During my time with the Seals, I came to an all-too-real conclusion that a majority of the general population has no idea how to treat people with disabilities. The truth is that we do not have a handle on how to treat people who have disabilities like proper human beings. Basic daily situations like standing in line for something or riding public transport were recipes for awkward glares and patronizing conversations from strangers.

Take for example, something as simple as going to the store. When you or I go to the store, we go in and get what we want mostly hassle free. Cashiers talk to you regularly. People mind their own business. It’s simple.

However, when shopping with a person who has a disability it is another matter entirely. In the aisles, shoppers would leave the ones that we were walking in because they felt uncomfortable. When an individual would attempt to pay for whatever they were buying, the cashier would often speak slower and louder to them. They weren’t hard of hearing, but even if they were, how would speaking louder make them understand what was being said any better? If the individual was shorter, sometimes the store employee would bend down to talk to them as if they were a child. Worse still, sometimes the cashier would ignore them completely and only communicate with me.

If someone treated you this way, you would be upset. You would feel disrespected and belittled. Most people don’t behave that way with others because treating someone in that manner is hurtful. Which makes this all the more problematic. This behavior is obviously considered offensive, yet it seems to be okay to treat people with disabilities, a large demographic in our population, in such a reprehensible manner without guilt.

According to the United States Census Bureau, there are over 37 million people with disabilities in the U.S. as of 2014. In California alone, there are over 4 million residents with disabilities. With that many people in our communities who have special needs, it is important to recognize what we are doing wrong first in order to change it.

I told him to put it away, but he wasn’t listening. I couldn’t physically move him away because A) We were not allowed to use force on individuals, and B) I didn’t want to touch a man who has his dong out. So I yelled at him louder to put it away before security came and tackled him. Eventually my insistent yelling got through to him and he finally put it away, but the damage had already been done. From that point on, whenever anyone who was there saw him around campus, they would think of him as the Flash:liable to streak by faster than a speeding bullet.

The worst thing was that despite being a “coach,” I was nowhere near prepared or qualified to deal with this. They trained us in what to do if an individual passes out. They trained us in what to do if we lose sight of our individual. What they did not train us for was what to do if our individual decides to Free Willy outside of SeaWorld.

If someone supposedly trained in this area like myself didn’t know what to think in this situation, how could I expect anyone else to know what to think?

While initially I pondered what life decisions had led me to this situation, I also wondered if incidents like this were the reason why the classrooms and facilities for disabled students on many campuses were in portable trailers separated from the rest of the classrooms.

But that thought led me to my next, and more important realization: Even when there was no school, we were rarely allowed to go somewhere populated and fun. We were told to go to a public library, a park, or some other place that was not often crowded.

I mean, I get it; the chances of people being around to see these transgressions are certainly lessened when we keep our heads down and away from other people. However, that in and of itself is problematic. When you don’t have the chance to be with a group of people often, your impressions of them will stem from what little interaction you have had with them in the past.

If the pants off, dance off incident is all anyone ever sees of this student, then there will be an unfair perception of him as someone who should not be allowed in public. If they only spent more time with him — with his pants on, naturally — they would see that he is a person and there were reasons why he behaved the way he did on this occasion. Instead, people continue to feel uncomfortable when others with disabilities are around and often pressure organizations like the one I worked for to keep them away from crowded places.

Paul Snitwongse, a freelance nonprofit worker, says this situation is echoed with an individual he works with on the weekends. He works with a high functioning young adult with Asperger’s who spends most of his free time at home. They hang out and play games together, but sometimes the individual will go and hang out with his friends instead.

“He likes to record the time he hangs out with his friends. During their conversations, his friends will talk mostly among themselves and leave him out of the conversation. I think because his friends don’t entirely understand his Asperger’s, they unconsciously leave him out,” said Snitwongse.

It’s easier to not deal with things we don’t understand. We are happy leaving those with disabilities on the sidelines away from our lives so that we don’t have to face our own discomfort with people who are a different from us or what we perceive as normal.

Simon Partridge, a life coach whose name was changed due to the position he still holds with Easter Seals, knows this concept all too well. He was working with three individuals in an outdoor mall one day when one of the individuals decided to separate from the group. He took off his shoes and began throwing them up in the air and at Simon. He began yelling at his coach, which drew the attention of shoppers and security. A guard came over and told Simon that he and his group were being disruptive and that they had to leave.

If a child does something similar, we think nothing of it because we understand that children can behave compulsively sometimes. This is not a comparison of behaviors between children and people with special needs, but a comparison of our attitude towards these behaviors. If we were a more informed public, we would understand that certain individuals may behave irrationally because they are frustrated or uncomfortable with a situation.

“I think people who were watching us don’t know the whole story. Sure, we know a little more about [people with special needs] now than we knew decades ago, but it is not enough. They are still misunderstood because we don’t see them or know enough about them,” said Partridge.

People without disabilities act irrationally in public all the time without the stigma that people with disabilities are saddled with. We’ve all seen that lady yell at the cashier because she wouldn’t get a refund without a receipt. “She must be having a bad day,” we say to ourselves. Or the guy who causes an accident and yells at everyone else as if it was their fault he crashed into them. We think, “Maybe it was the other driver who hit him?”

But because we see people without disabilities often, we understand that those people don’t act like that all the time and are usually pretty reasonable. With people who have disabilities, we don’t see them often enough to realize that they behave as we do most of the time.

All we remember are the “abnormal” behaviors, outbursts, and actions. We don’t see a person with wants and needs, much like our own. We don’t see another human being. Not really.

This lends itself to the thought that they aren’t a complete person. They are not looked at or treated like equals, as such we often forget that they are people who feel joy and pain just like the rest of us.

Such was the case of another student I worked with, a music major and a jazz fanatic who has Asperger’s. At his side, I watched as he struggled with being unable to interact with teachers and other students. Which was why I was there; my role in his life was to help him navigate the daily grind that is college.

There wasn’t much I could do for him in the way of his studies. I love music, but know nothing about how it is made. Even so, I was there for his entire semester and witnessed the difficulties of his situation.

Often, school would get the better of him. Sometimes when he thought I wasn’t looking, I would catch him hanging his head and fighting back the tears because his schoolwork was difficult and he felt like no one could help him. His mental disorder made it hard for him to connect with his peers and to ask for help from them or his professor. It was like there was an invisible wall separating him from his peers, and he often confessed that he felt envious of how lucky they were to not have to deal with a disability as school would be so much simpler without one.

But he never quit. He knew that he was going to graduate and transfer to a university no matter what it took. I only worked with him for one semester, but in that one semester I witnessed how hard he was willing to work for what he wanted. He never let his disability stand in the way of what he wanted to be.

This individual — this person — taught me something valuable in the time I spent with him: He showed me that just because you have a disability doesn’t mean that it dictates how your life plays out. After that semester, I decided to quit my job and go back to college.

Unintentionally, just from having met him, this student changed my life. Imagine what other people could learn just from socializing with people who have disabilities more regularly. Sure, they may pull their pants down from time to time or throw their shoes, but we do that sometimes too. It just takes some alcohol or a really bad day to get us there. These people are still human and deserve respect. They do not deserve to be treated like invalids because of their disabilities.

A woman recently came into my work, serendipitously, on World Autism Awareness Day. She was shopping with her 13-year-old son who is Autistic. He was speaking loudly at the video games on display and mimicked the sound effects they were making. She explained that a couple of years ago, a family tragedy had hit her family and her son particularly hard. He began behaving louder than usual while he dealt with the situation.

One day, she was shopping at a store when it was time for her to pay. Her son was standing next to her while he was being noticeably louder than other customers and making sound effects. The person ringing her up lectured her on how she was parenting her son and suggested that she needed to medicate him or put him in a “home.”

Her only response was to cry at the thought that her son would have to deal with this kind of ignorance for the rest of his life.

Society needs to break this cycle of willful ignorance. No one should ever have to be treated poorly because of their disability. For obvious reasons, a disability may mean that they are treated differently as they will sometimes have different needs. But think of these differences like building a ramp alongside stairs: it should never be less, but more; an added change that was needed to make our world, as in all of us, more inclusive and accessible.

It’s important to recognized that it’s about becoming more understanding and accepting of a significant group of people and their needs rather than not treating them differently outright. Sometimes, you will treat them differently. But it should be a change made to create an equally opportunistic atmosphere where we can all thrive, regardless of what holds us back.

While awkward at first, the more comfortable our society becomes with people with disabilities the less we’ll see a mother forced to tears by the way we misunderstand and treat her son. And who knows, you may just learn something about yourself from an unlikely someone who was never really all that different from yourself in the first place.

Illustration by Suzanne Tumbos / Tumblr