From Home

I went back to Chile to rediscover my identity as a Hispanic man living in the United States for the past 19 years.

Living in the United States has done something to me. It’s odd, difficult to wrap my tongue around —and even difficult to accept that, yes, I’m a “gringo.” I have lost sharpness in my Spanish, something I realized during my time in Santiago, Chile this past summer. But to be politically correct, I’m a first generation Chilean and proud to be one. My life as a Hispanic young man has always been a quest to fit in — to find my identity as both a human and artist, seeking answers to the questions about his roots and heritage.

For most of my life, I grew up wondering about the absence of my father, Luis Hidalgo. I found out 10 years ago that he was a photographer for the Associated Press in Chile. This was around the time we began to maintain close contact. Both of my parents are artists, however, my mother inherited painting as her medium due to the influence from family members on her father’s side.

At 20, my mother fought hard for me to have a better life. She was a single mother, studying at the university and taking care of me. We lived in Providencia in Santiago until I was 4. I went on to live in the United States with my grandmother for one year so my mother could finish her studies and get her degree. The intention of the move was only to be temporary.

But the year stretched on to 19 years away from home, or what I perceived was home. However, home actually became North Los Angeles. My childhood environment was rich in life, art, music and politics. I learned about important figures such as, Pablo Neruda, Salvador Allende, Che Guevara, Frida Kahlo and other notable people from Latin America. Most of the people in my family are musicians, painters and great independent thinkers in their own respective circles. I just wanted to take pictures; to become a photographer to tell stories that matter. After years of not seeing my father, the day finally arrived. All of those hours spent on Skype were incomparable to the two minutes when I hugged my father at the airport. His scent, his touch, his voice all synchronized into a moment of raw emotion. I felt like a little boy again. Fatherhood. I have lived through the pain of an absent father, but that remorse was put behind me. I grew older and I began to forgive my past, and after further self-evaluation, I forgave myself, too. There were many years lost in our relationship, years that we could never gain back. But this moment had given me a sense of closure.

Family intimacy is an essential aspect to someone’s journey from childhood to adulthood. My new continuing project, “From Home,” deals with the absence of family presence. It is a portrait of my personal familial experience intertwined with our affections and historical value that people have for one another. In other words, it’s the memories that shape our ideal values revolving around the foundation of family: love.

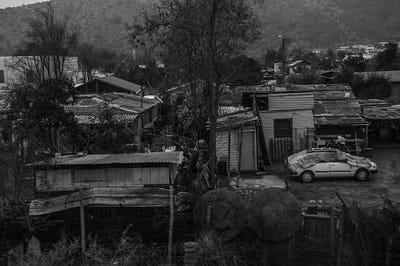

I spent a lot of time in the Villa Portales where my great grandfather, Julio Beas, raised his six children in the 1960s. Nearly six decades later, two of his children reside in the Villa Portales. Chilean history is restless on the dry terrain. The Villa Portales is made up of 19 block apartments built in the 1960s, housing over 2,000 families today. It is being labeled as an “architectural attraction.” The Andes emerge from the dirt roads, painting the mythical panorama that Chile is.

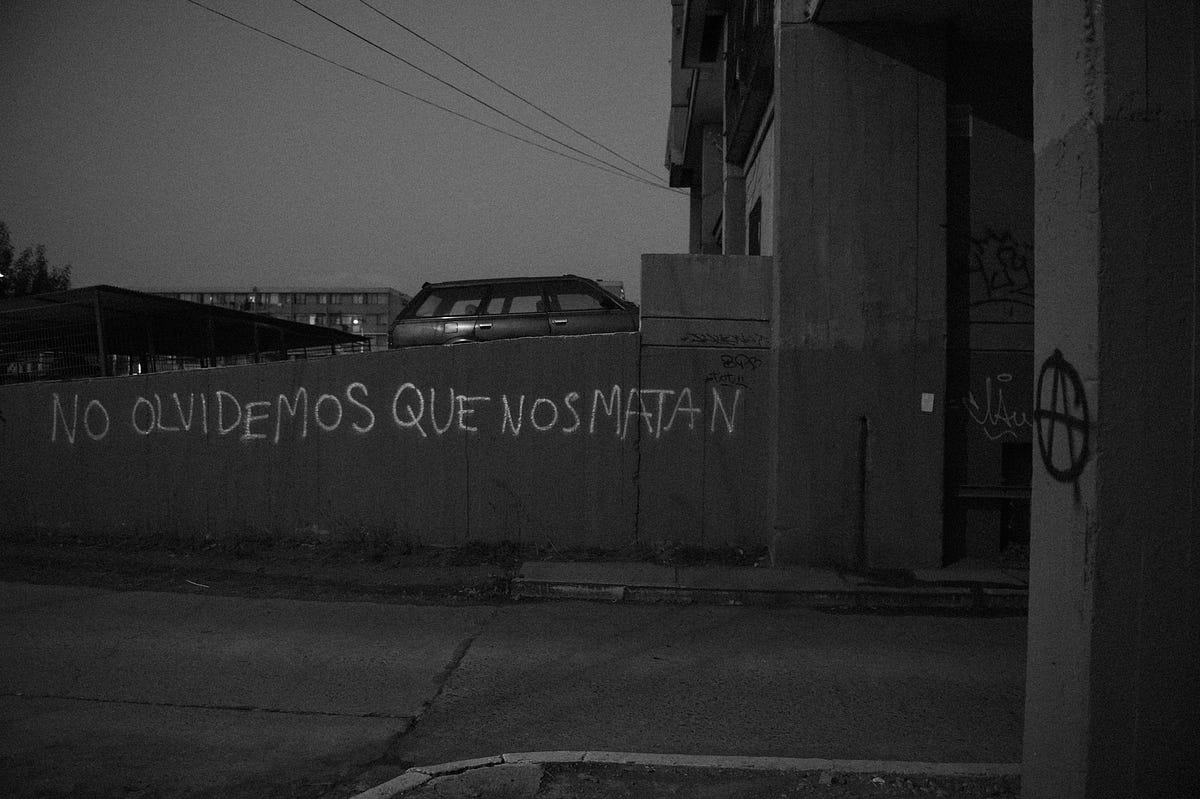

During the beginning of its time, the Villa Portales was mostly characterized by left-wing organizations that revolved around its intensive activism. On September 11, 1973, the course of Chilean history radically changed. Socialist President Salvador Allende was overthrown and killed by General Augusto Pinochet’s military. According to reports, Allende barricaded himself in La Moneda, the presidential palace, as air force jets bombed the building. He exchanged gunfire with an automatic rifle that was given to him by Cuban leader Fidel Castro, only to turn the gun on himself. However, there are still speculations about Allende’s fatality. Loyalists to Allende were also caught between crossfire in the Villa Portales. Buildings were bombed and many of its residents disappeared, or were captured and tortured.

My great grandfather, Julio Beas, never involved himself or his family with the opposition to Pinochet, at least with armed force. Instead, the Beas family created their own world view through their artwork. They seemed to separate themselves from politics. My grandfather, Patrick Beas, a musician, went on to study at University of Chile, a block away from the Villa Portales. University of Chile is a school known for its left-wing politics. In fact, both Salvador Allende and Victor Jara studied there. The 1970s was an impactful decade for many Chileans and for the country itself, which still seems to be healing.

The emerging middle class continues to struggle to find its foundational support, while the rich thrive off copper export and international trade. Chile has become one of the few Latin American countries to prosper, but in most recent times, its economic distribution has deficiently created opportunity. The richest 10 percent of Chileans collect $42 out of every $100 worth of disposable income, according to data from the World Bank, published in The New York Times. Additionally, the country shares a common plague amongst its Latin American counterparts: corruption under the power of the rich and oligarchy.

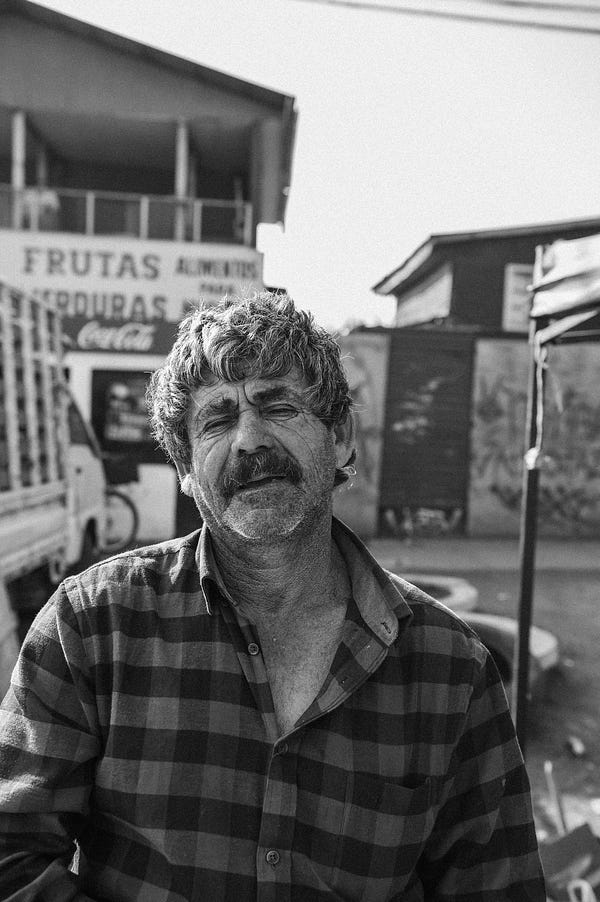

Chile is beautifully rich and oppressed. It is important to walk the streets, to taste the foods sold on the corners, to take the underground trains, to talk to natives, and to drink their wine. Engagement is a powerful technique that molds an outsider’s perspective into a local one. Despite the inequality, Chile does not remain silent. It speaks with its art, music, culture and intellect.

Chileans are hard working class citizens who live fulfilled lives with very little, like most of my family members whom I met. These images are pieces from the experience. Some are written, and others, captured through a lens. Chile is a representation of who I am, but Chile is also a fragmented relationship that we share, distanced between thousands of miles of land and mountaintops.

This story is written and produced by Pablo Unzueta. For more work, follow here. All rights reserved.