Freak Show: A Reclamation

Identity and acceptance through the work and life of Diane Arbus

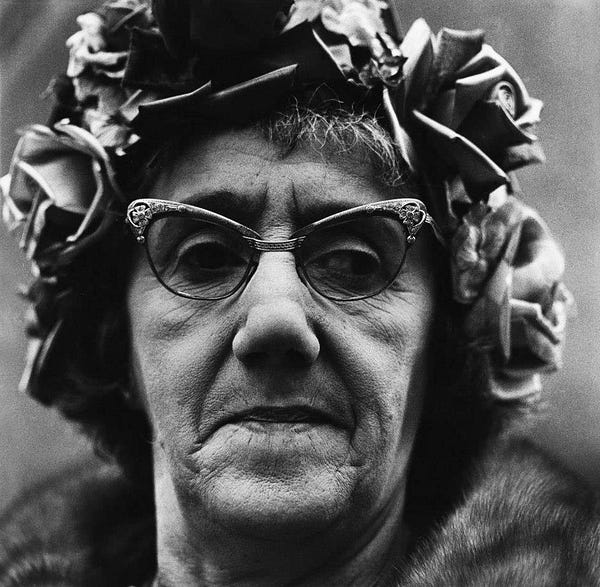

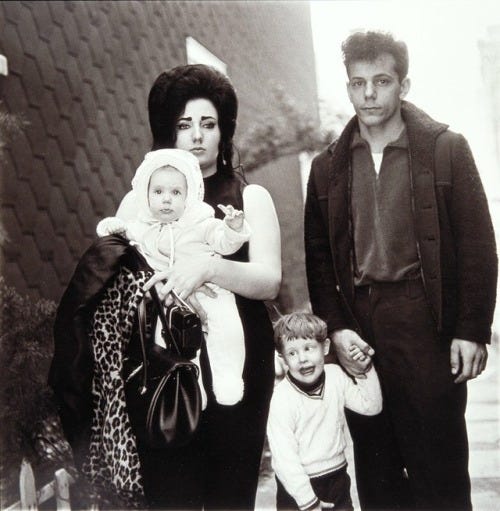

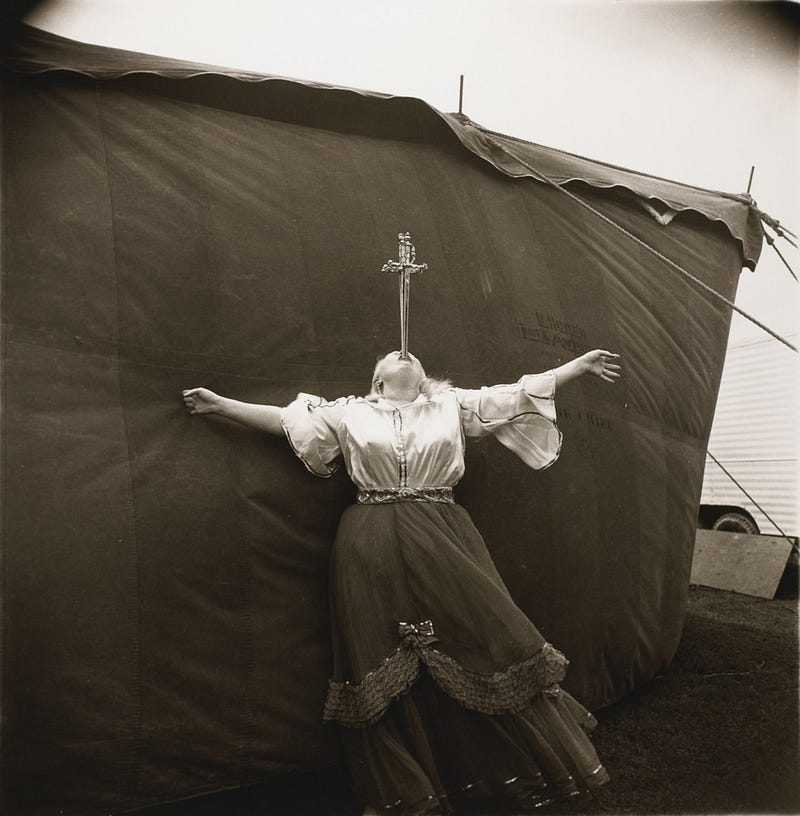

Known for her striking black and white portraits, Diane Arbus’s work is famous for its duality and reverence of humanity in all forms. Her subjects range from nuns to nudists, celebrities to carnies, children to the elderly, showgirls to transwomen — all singing the stubborn song of the heart: I am I am I am. Born in 1923 and died in 1971, the New York native had an eye for subjects with a story written plainly on their skin, be it loudly through their choice of adornments or quietly with an expression. Her empathy rings out from every image, presenting subjects without judgment or fear, but perhaps with a little love.

I mean, it’s very subtle and a little embarrassing to me, but I would really believe there are things which nobody would see unless I photographed them. -Diane Arbus

She captures these quiet moments with the eyes of a poet, and although she is well regarded in photography, this sentiment is not universal. Her work has a similar air to the peculiar fascinations of a young child, a sense of marvel at something grotesque or mundane that grown folk close their eyes to. Not everyone can see the appeal of a smushed lizard or a wet muddy leaf, but we all feign interest when presented on a child’s eager palm.

Active during a time where hard lines were drawn between what is normal and what is abnormal, Arbus’s intentions behind photographing outliers of society are oft-debated. Was it because of the pervasive allure of a sideshow? To humiliate its subjects? The audience? Or to show the idiot village that is America, as Susan Sontag once wrote in her 1973 critical essay entitled “Freak Show”? Sontag mourned the lack of beauty and chided Arbus for her inability to elicit compassion from the audience for the subject. One would argue Arbus’s stark allowance of existence through photography goes beyond compassion. The subjects aren’t gussied up, no efforts are made to highlight their differences. They are presented without fanfare or concealment, simply as they are and how they exist in the world. In Arbus’s work, her subjects are given a luxury they perhaps seldom received in the harshness of the world — the acknowledgment of their inherent humanity.

Her work is polarizing and challenging, especially to audiences of the era. Early reactions to “A Young Man in Curlers at Home on West 20th Street,” for example, were strong. Someone spat on it during its showing at the Museum of Modern Art in 1967. Although advancements benefiting the queer community were beginning to be put in place by Mayor John Lindsay (like the outlawing of police entrapment in gay bars and intrusive questions involving sexual orientation in N.Y.C. hiring practices), tension continued to surround them. A mere two years later in 1969, the tension reached its critical point and the historic Stonewall Riots occurred. This was a time where the queer community was not only ostracized, but actively treated as lower-class citizens, and stripped of the rights afforded to cisgender heterosexuals. Their very existence was a radical action. The quiet moments captured in Arbus’s work humanized them.

Nothing is ever the same as they said it was. If you scrutinize reality closely enough, if in some way you really, really get to it, it becomes fantastic. -Diane Arbus

Because of her affluent upbringing, some critics have accused her of being another exploitative voyeur, intruding upon the privacy of these individuals and taking advantage of their ostracization from society for shock value. This has been largely disproven by the fact that she befriended her subjects, and disregarded the canons of acceptable distance between photographer and subject. The intimacy found in her work is found in that close distance, and in the familiar setting that surround her subjects. That intimacy is often what is so polarizing about her work — how can her subjects continue to be the bane of society if they’re human after all?

There is a quality of legend about freaks. Like a person in a fairy tale who stops you and demands that you answer a riddle. Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a dramatic experience. Freaks are born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life. They’re aristocrats. — Diane Arbus

Because of her lifelong struggle with depression and mental illness, critics pontificate on whether she was attracted to those on the fringes of society because she saw herself in them. Anyone with trauma can agree, it’s easy to spot those who are your kin. But saying her subjects and herself were damaged, and that’s why they were great is derivative of her work, and everyone involved. Her intention and obsession lie in the inherent humanity in her work. There is a sadness to be found not in her work, per se, but within the audience — when they realize that her subjects are not the monsters they have been made out to be. Just people, with the bravery to be themselves in a world that cares not for them.

I go up and down a lot. Maybe I’ve always been like that. Partly what happens though is I get filled with energy and joy and I begin lots of things or think about what I want to do and get all breathless with excitement and then quite suddenly either through tiredness or a disappointment or something more mysterious the energy vanishes, leaving me harassed, swamped, distraught, frightened by the very things I thought I was so eager for! — Diane Arbus

Lightning rods give out over time, as all things do. Diane Arbus committed suicide on July 26, 1971. The year after, in 1972, she became the first photographer to be included in the Venice Biennale where Hilton Kramer attributed her photographs with “the overwhelming sensation of the American Pavilion. If one’s natural tendency is to be skeptical about a legend, it must be said that all suspicion vanishes in the presence of the Arbus work, which is extremely powerful and very strange.” It is vital to revisit Diane Arbus’s work to remind oneself of the wide expanse of humanity, the intrinsic value of a human life, and the glory of being a freak.

There are and have been and will be an infinite number of things on earth. Individuals, all different, all wanting different things, all looking different. Everything that has been on earth has been different from every other thing. That is what I love: the differences, the uniqueness of all things and the importance of life…I see something that seems wonderful; I see the divineness in ordinary things. — Diane Arbus