Gay, Latino and Macho

The struggle to be queer and out in a machismo culture

Story by Albert Serna Jr. and Adolfo Tigerino

Forced onto a school bus as the day came to an end on a Thursday in 2005, Josue was frightened and uncertain what the future held for him and his companions. Chaperons from the strict Latino Pentecostal church took away all methods of communication so they were virtually removed from society. Arriving at a ranch in the middle of nowhere under the cover of darkness, the teens were forced into separate rooms. Each day they were made to pray and denounce their sexuality. It was believed that the teens had demons controlling them. And, before he was allowed to be “cured,” the scared 17-year-old was held down against his will while several people screamed in attempts to speak with the alleged demons within.

They performed an exorcism to cure him of his homosexuality.

For Josue Velasquez, now 26, the idea of being gay and Latino did not sit well with his religious mother. She upheld a standard of masculinity called machismo that conflicted with the person Velasquez is. In the Latino culture there is a belief that men need to be hyper-masculine, domineering, controlling, and without the slightest hint of femininity. The culture of machismo is a conflict between the two identities; gay and Latino. The ideology requires such a high standard of masculinity that it is nearly impossible to reach. Critics of machismo such as journalist and feminist Germaine Greer have said, “The tragedy of machismo is that a man is never quite man enough.”

Being raised in a machismo culture impacted Velasquez’s life, and his future. As a teen, he dreamed of becoming a fashion designer. His mother would crush those dreams one day when he showed her his prized drawings. He was a junior in high school and had spent most of the year preparing a portfolio. When he told her of his plans to attend fashion design school, she walked him out to the yard, threw his drawings in the barbecue, and made him light his portfolio on fire.

Her son, she said, would be a man, not a maricón, a derogatory term used to describe gay Latino men or any man who is effeminate.

“She said that fashion was not a man’s job,” Velasquez said. “I felt so defeated. I let go of that dream because I knew I would never get the support from my mother or family.”

Velasquez now majors in anthropology at University of California at Irvine. He said his mother even tried to get him to skip college and go to a vocational career. “Never in my life would I do that. It makes me laugh because I would like to think that my family would want me to aim higher.”

Velasquez has sashayed away from machismo and embraced the elegance of drag culture when he hits the stage as “La Buganvilia.”

“I always told people that I didn’t like that stuff, and that I would never dress up like a woman because I was a man, a gay man, and that’s how God had made me,” Velasquez said.

It wasn’t until 2010 that the show RuPauls’ Drag Race changed the way he viewed drag, but his first attempt was all for fun. Now drag is an integral part of who he is. “For now, drag is an art of expression for me. It is a way that I can still live my dream of fashion and costume making. I make all of my costumes and the costumes for other drag queens.” But not all endings are as glamorous as Velasquez’s.

In the barrios of Los Angeles, the culture of Machismo thrives. So many men are born and raised to uphold the masculine identity and pass it along to their sons. Take Felix Rios*, a 35 year-old Mexican who grew up in East Los Angeles surrounded by figures meant to be idolized; the men who worked construction all day and provided for their families or the caballeros who toiled on the field. Early on, Rios knew he was different, but an experience with his father would forever leave a scar.

“My dad was a big mean guy. He took my brother and I out to the desert with a bunch of guys. They said it was going to just be the men on a camping trip so I was excited,” Rios said.

And then things went terribly wrong. “We went to a small house and my dad and the other men knocked on the door. A man answered and I knew from his look something wasn’t right.”

The man was a ranch hand who they perceived as gay. “They pulled him out and just attacked him; they beat him pretty badly. I remember my brothers and the other boys cheering.” Rios said he thought they were going to kill him. “At that moment I knew I wasn’t going to be like the ranch hand; I would never be a maricón,” Rios said.

Rios, who is married to a woman and expecting a son, said he does not ever plan to come out. “If I ever told anyone that I had sex with men, they would think less of me. I wouldn’t be a man to them,” Rios said.

This may be why the queer underground is growing in record numbers as more and more men come out. Some bars and nightclubs have sprung up to cater to the Latino men who are gay but still retain their Machismo culture. Rios said that while he is attracted to men, he asserts that he is straight. For men like Rios, gay bars and clubs allow an escape from what society expects of them. “Outside [of the nightclub] you have to be strong; you have to able to do everything a man is expected to do, and it’s hard. There is no room to be yourself,” Rios said.

Rios likes the freedom he gets from going to gay bars where no one knows his name. “When I’m there dancing, making out with whoever I’m with, I don’t have to pretend. Yes I’m macho, and perhaps it’s a lie, but in there we all know.” This fear has led many ‘straight’ married men to lead out secret trysts using dating apps like adam4adam, an online hookup site and app.

As for concerns that his wife may find out that he has sex with men, Rios has had some close calls. “[My lover] would text me and for a while my wife thought I was cheating on her with a woman. I had to break things off and change my number so that my wife wouldn’t leave. It hurt, but that’s just how it is.”

Rios said this has not stopped him from seeking out sexual relationships with other men or going to the bars when he can. He also plans to raise his son to be masculine. “I’m still going to have my men on the side, I need it, but that doesn’t mean I can’t show my son how to act. He needs to be strong and make the community proud. I don’t want him to be like me; I don’t want him to hide himself, but I don’t want him to be a sissy.”

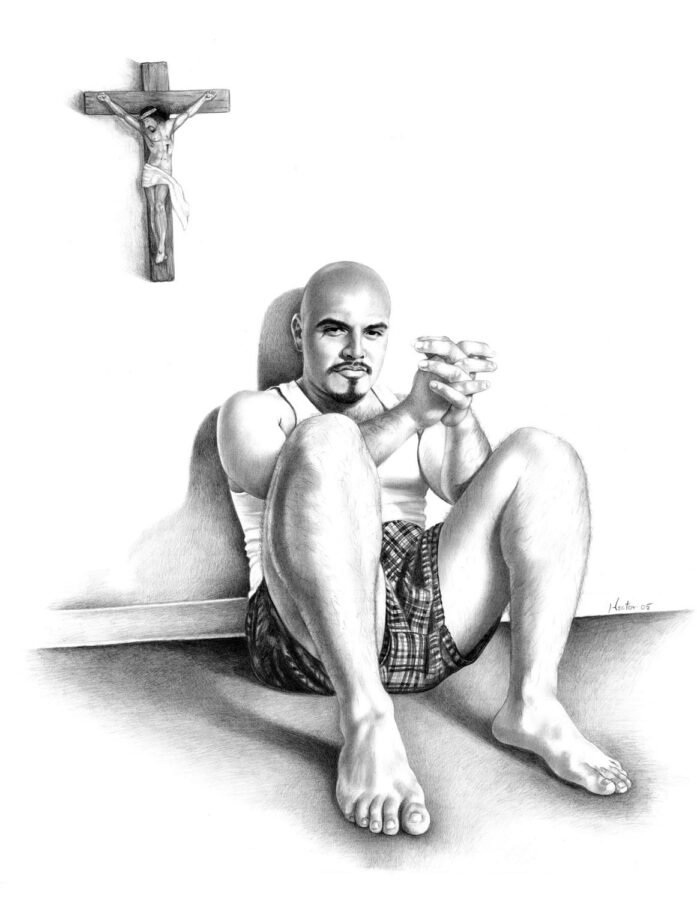

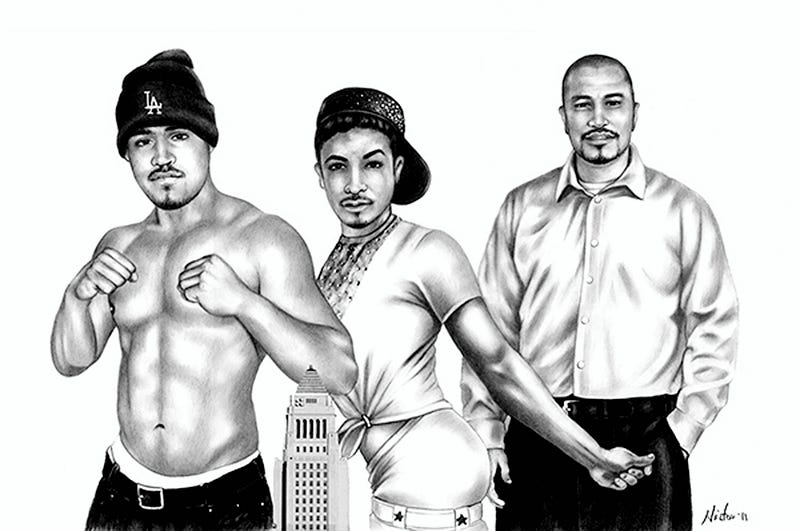

Not everyone agrees with the tradition of machismo. Artist Hector Silva, who was born in Mexico and immigrated to San Diego at 17, is all too aware how men are brought up to uphold the oftentimes unreachable standard of masculinity that machismo imposes. “There is a lot of machismo in Mexico and they pass it down. I think it’s very wrong the way they teach young men, boys, about machismo,” Silva said.

Through his art, Silva brings to life the sub-culture of gay Latino men in ways that the nightclubs cannot, and offers an inside look to what happens in the community. He depicts the traditionally masculine “homeboy” or “ranchero” in homoerotic poses and acts, and has been heralded by many as shining a light on the gay Latino community. Silva explained the meaning behind his art. “I just wanted to show a different side of machismo in a very soft light. I wanted to show that it’s okay to be macho, and soft and gentle at the same time.”

He added that he likes to include religious symbols as a contrast to what the church teaches about homosexuality. “With the homoerotic art, I wanted to tell people it’s okay even though you’re religious. I don’t think it’s a sin or anything like that; you can be gay and Catholic or religious.”

Rios, who has seen Silva’s art, said he appreciates what the artist has done for the Latino community, but added that he would never buy or display a piece out of fear. “His art is very hot and very sexy, but I couldn’t buy it,” Rios said.

In the case of people like Rios, Silva said he sympathizes with their lack of self-acceptance and understands why they do not come out. “Usually Latinos will do that because they are afraid to come out, and I feel bad for those people that society doesn’t allow them to be themselves. It’s not their fault society forces them to live a double life.”

However, Silva does not care what men like Rios say about their sexual orientation, he believes they are gay.

“[A man] has got to be gay if he’s having sex with men. No straight man would have sex with men unless they are gay. I don’t care what they say, they’re gay.”

Age is also a key factor dealing with Machismo culture. Many older men like Rios are unable to reconcile with both their gay and Latino identities because the acceptance of gay culture is fairly recent. However, for men like Miguel Guillen, an independent art contractor, being gay and Latino is an integral part of who his is. Born in Mexico, Guillen’s family moved the United States when he was 6 months old. He traveled around with his farm worker parents until they settled in the migrant farming town of La Conner, Washington in the 1960s.

Now 55, Guillen has known he is gay for most of his life, and because his father was an artist, he grew up in a very liberal household. There was never a moment where he needed to come out; his sexuality was just accepted. However, the expectation of Machismo outside of his home was harsh. Guillen dated girls and upheld a maschismo identity. It was not until he moved to Seattle that he would experience the freedom of living as a gay man. “When I started actually identifying and actually moving into being a gay person, it made me sort of break away.”

Despite the stigmas they face, many queer Latino men are beginning to forge a new life for themselves. They are creating a unique identity that encompasses both their Latino heritage and their sexuality. For Velasquez, this was not an easy task, but he believes it was the best thing to do. He now lives with his boyfriend and is glad to be free and on his own. “Just get out of there. Be your own person and forget what anyone else says. It’s better to just be your own person. Fuck everyone else.”

Editor’s Note: To protect his privacy, Rios’ name has been changed.

Substance is a publication of the Mt. San Antonio College Journalism Program. The program recently moved its newsroom over to Medium as part of a one-year experiment. Read about it here: https://medium.com/substance/the-experiment-be947b2ba13e