The Biggest Nuclear Threat to America

Isn’t Who You’d Think

“Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” –J. Robert Oppenheimer, father of the atomic bomb.

Due to major tumultuous world events such as the Iran nuclear crisis and the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists moved the Doomsday Clock two minutes forward. The legendary clock, which measures how close humanity is to annihilation, now stands three minutes to midnight. Factors such as the modernization of nuclear weapons by Russia and the United States, the disintegration of nuclear treaties, and the growing threat of global warming have moved the hands of the symbolic clock closer to global catastrophe.

This is the closest the Doomsday Clock has been to midnight since 1984 when nuclear peace talks between the U.S. and the Soviet Union shutdown completely and America contemplated expanding its missile capabilities to outer space increasing concerns of a new arms race between both superpowers during the Cold War.

Many comparisons are drawn between the budding relations of America and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, and America and Russia today; except weapons of mass destruction have only grown more advanced and peace talks more convoluted.

Comparing current relations to those of the Cold War seems like an abstraction. After all, America has a tendency to pave over the past with the blind optimism that the past will always stay behind — never to repeat again.

Remnants of the Cold War can still be found scattered across the greater Los Angeles area from a time when fear of a nuclear attack at the hands of the Soviet Union was daily, and nuclear blast duck-and-cover drills in schools was routine.

Between 1956 and 1974, a ring of 16 nuclear warhead launch sites encompassed Los Angeles ready to intercept Soviet missiles. The project was named Nike after the Greek goddess of victory. Each launch site carried Nike Ajax anti-aircraft missiles and some sites carried the Nike Hercules long-range missiles with a nuclear warhead component. Residents near these sites knew very little about their functions, and even less about the nuclear warheads stored in their communities.

Only the ruins of six of the launch sites remain. The rest have been demolished, and the land reused by local city governance despite the efforts of some community leaders to preserve the historic sites. Located in South El Monte at the edge of Whittier Narrows, only the doors and cement platforms remain of launch site LA-14. It is surrounded by overgrown brush and enclosed by a chain link fence marked with a “No Trespassing” sign. No one in the adjacent tennis courts or the playground across from the site would ever know that just meters away instruments of mass destruction were once housed. The site is now storage for construction equipment and home to several white-tailed rabbits that make the 20 foot empty shafts their habitat.

A map of all other remaining Nike launch sites can be found here.

Scattered throughout the Southland are Civil Defense Sirens placed during the Cold War to alert citizens of an impending nuclear attack by the Soviet Union. The attack never came, and the Nike Missile sites became empty shells, but the sirens still remain — making for an interesting scavenger hunt across Los Angeles. About 225 sirens have been cataloged in the greater LA area ranging from Sylmar in the North, Gardena in the South, Malibu in the west, and El Monte in the East. During the Cold War tension, the sirens sounded off routinely on the last Friday of the month punctually at 10 a.m.

Just a short drive from LA-14 are four sirens: two “wire spool” designs and two “birdhouse” designs. The first is at the intersection of Alhambra Avenue and Lombardy Boulevard just behind a tire shop. The wire spool siren is attached to a 30-foot steel pole. The other wire spool can be found next to an O’Reilly Auto Parts at the corner of Huntington Drive and Van Horne Avenue.

Both of the birdhouse sirens are found within a six-minute drive from each other; one at Topaz Street and Pyrites Street northeast of Huntington Drive Elementary School; and the other at Valley Boulevard and Ronda Drive in Montecito Heights.

A map of all Civil defense Sirens and their addresses can be found here.

America has always been fearful of nuclear annihilation from other nations but the closest we have ever been as a country to nuclear catastrophe has been by our own hand. On January 1961, a U.S. Air Force aircraft accidentally dropped two hydrogen bombs over Goldsboro, North Carolina. Each bomb was 260 times more powerful than the nuclear bomb that ravaged Hiroshima. One of the bombs armed itself when all but one safety controls failed. Since record of that incident became declassified, at least 700 other accidents involving nuclear bombs over U.S. soil began to emerge.

With the modernization of our own nuclear arsenal, are modern cities in America at risk from another close call? What would a nuclear detonation look like in Los Angeles today?

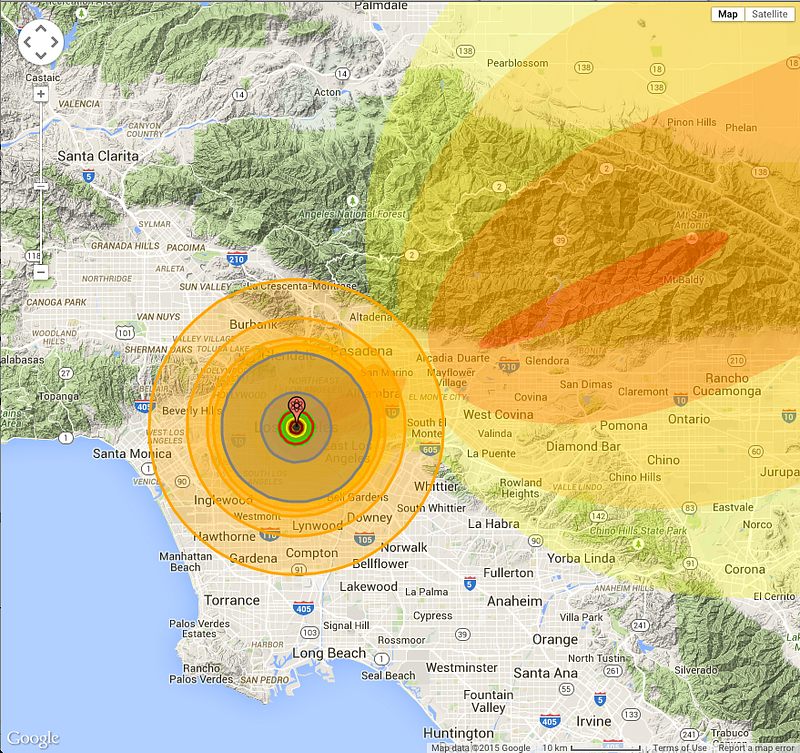

Alex Wellerstein, a historian of science at the Stevens Institute of Technology developed Nukemap, a web based simulator that allows the user to see the damage of historical and current nuclear bombs on any city in the world using Google Maps.

The picture above is what, according to Nukemap, the devastation would look like over Los Angeles if the largest bomb currently in the U.S. arsenal, the B-83 (75 times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima), was inadvertently detonated in Los Angeles today.

The estimated death toll would be over 410,000 and injuries over 740,000. Over 106 hospitals, 17 fire stations, 216 schools, and 200 churches would be destroyed. A crater 300 feet deep and with a radius of 688 feet would remain where Los Angeles City Hall, The Los Angeles Times building, and transit building stood. The ground around the crater would uplift by at least 20 feet due to debris blasted out from the impact with a 410 meter radius around the impact zone. A nuclear fireball would instantly vaporize everything between Chinatown to the north, Skidrow to the South, the LA River to the East, and Bunker Hill to the West. Anyone caught in the blast at the Dodger Stadium, USC Medical Center, Staples Center, or the Arts District would receive a lethal dose of radiation. The communities of Echo Park, West Lake, and Boyle Heights would be demolished by a shockwave equivalent to 20psi of compressed air with a 100 percent mortality rate. Anyone living within 2.31 km outside of the air blast zone would suffer from radiation exposure with a 50–90 percent mortality rate. Victims in this zone would die in a matter of hours or weeks after surviving the fireball and subsequent air blast.

As the air blast dissipates to 5 psi, residential housing is leveled but concrete structures would remain standing but severely damaged in the areas of East Hollywood, Koreatown, East Los Angeles, and Montecito Heights. Windows as far away from the epicenter as Glendale, Alhambra, South Gate, Baldwin hills, and West Hollywood would shatter; injuring anyone who might rush to their windows after seeing a flash of light that would momentarily over power the sun. A thermal radiation blast would reach up to 20 miles away from the center in all directions. Anyone caught outside during the blast would suffer from first, second, and third degree burns as far away as Santa Monica, Burbank, Compton, Pasadena, Whittier, and El Monte.

The nuclear fallout cloud would reach as far east as Las Vegas, Nevada. Anyone in the Los Angeles Forest and Mt. Baldy area would receive a deadly dose of fallout radiation.

“Being told that a certain nuclear weapon emits 500 rem of radiation over a given radius of meters means little to the average person,” Wellerstein said in a post from the Stevens Institute of technology. “But when you pair that with an illustration of the distance over a city they know well, along with a qualitative description of the effects of 500 rem, suddenly the ultimate meaning of this becomes clear to anyone, technical or not.”

Wellerstein’s Nukemap is meant to engage the user in a conversation about nuclear weapons, and not terrify the user. The argument for nuclear weapons has always been that it deters other “trigger happy” nations from using it on Americans. But as illustrated from the Goldsboro incident, we are just as much of a threat to ourselves as any nation with nuclear capabilities. America is also the only country in history to have ever deployed such weapons of mass destruction against a civilian population.

Currently, there are over 16000 nuclear weapons worldwide. Most of the bombs are stock piled by Russia (8000 warheads) and the United States (7300 warheads). Each individual bomb is capable of the destruction of any city with subsequent damage as outlined by Nukemap.

So, what’s the solution? The best nuclear deterrent in any scenario is a world without nuclear weapons. For now, we can only hope that no citizen of the world ever experiences first hand the devastating effects of nuclear war.

Photo illustration by Cynthia Schroeder

Substance is a publication of the Mt. San Antonio College Journalism Program. The program recently moved its newsroom over to Medium as part of a one-year experiment. Read about it here.