You Don’t Know ‘Jack’

What Jack, my pet monkey, taught me

Living in Africa wasn’t the experience that I had imagined it would be. While packing my suitcase to travel from Los Angeles to Ghana, West Africa as a thirteen-year-old tomboy, I welcomed what I thought would be an opportunity for daily adventures straight out of the Wild Thornberrys cartoon.

Mud huts, grassy savannas, and tall roaming giraffes in my backyard were some of the things I anticipated seeing, so I bid my friends adieu at the end of sixth grade and stepped into a foreign, yet strangely familiar world — all on my mother’s whim of wanting her six bratty children to become more cultured and appreciative of her hard work.

To my shock and dismay, I arrived in Africa to find a city, nothing at all like the images of Africa I had seen on the Discovery Channel, nor in sad commercials requesting donations to feed starving children in shaggy villages. I learned that Ghanaian locals refer to those types of areas as “the bush,” akin to the American “the middle of nowhere.”

To anyone who donated to one of those sad children in the commercials, those areas do exist. I got to visit “the bush” while there. I think I may have even seen a tumbleweed, although, I could have just imagined it from too many Western films growing up. The imagery is the same though. The Bush is wild, extra dusty, and has more “madmen,” mentally unstable individuals who roam around predominantly nude, than the city where I lived. I lived in Accra, the capitol.

When I wasn’t traveling by foot — because people are less lazy and things were proximate to our residence, so we walked — I took a taxi everywhere, and I didn’t see a single lion in my two years in Africa. I asked where all of the lions were when I first arrived. I was given the strangest look by Ghanaian natives, and told “in the zoo.” From that moment, I started learning a major life lesson.

Experiencing another culture firsthand is a wonderful way to have romantic, glamorized ideals totally shattered — after all, life is rarely like what is seen in TV shows and movies.

Riding horses along a sandy beach, for example, looked beautiful and graceful in movies. I had romanticized the experience until I tried it. Riding a horse along a beautiful coastline is downright terrifying. It wasn’t until I was about 10 feet tall on horseback, staring down into crashing waves that I realized the frightening possibilities: the horse could lose its footing; the waves could rise too quickly, and I could suddenly be crushed and drowned simultaneously if the horse were to fall on top of me in the ocean.

The glamour of Hollywood had not only disillusioned me, but my Ghanaian peers too.

Everyone was shocked to learn that I was born in California and not a natural blond who enjoyed surfing on ever-sunny weekends.

I asked one of my Ghanaian peers, Matilda Blankson, why she thought everyone from California had blond hair and surfed. She said, “not everyone,” but she thought most people did because that’s what she saw on the “Teli.” In fact, I’ve never even been surfing, I informed her. The closest I’ve come to surfing was boogie-boarding at the beach, and from what I recalled, that wasn’t a great experience either — mostly because of the sand burn, like rug burn, but worse. Not only did the coarse sand give me a million micro-abrasions, I also ended up with sand in uncomfortable places.

But one of the most egregious “Hollywood” lies that broke my childhood perspective were the lies about the adorable, lovable, fuzzy, seemingly cuddle-able animals. So many movies that I watched growing up contained animals. Being an animal lover, I’ve owned many of the animals I saw in movies. I’ve enjoyed cats and dogs as pets, even though I was a tad disappointed when mine didn’t talk — thanks Oliver & Company. I’ve had fish, reptiles, and other small critters: a snake, Russian Tortoise, lizard, frog, hamsters, rabbits, fish — so many flushed fish! — and a yellow bird named “Tweety.”

I even had an adorable pet pot-bellied pig, like in the movie Babe, that my mother sadistically named “Bakey,” after “bacon.” She wanted to also get a pet chicken to name “Eggs” so that we could have “Eggs and Bakey,” but we didn’t get the chicken before moving to Africa due to weird zoning laws that said we could have a pet pig, but couldn’t have a pet chicken.

I was sad about leaving Bakey behind to go to Africa because she was my most spoiled pet. She lived indoors and couldn’t fall asleep unless I held her, hummed her lullabies, and rocked her like a baby — in an actual rocking chair, too. I even fed her from a bottle, but I was happy we found her new owners, who promised “crossed-their-hearts” not to eat her, and so like most children who negotiate for better toys, I left her behind because my mom reassured me I would have a new pet, a pet monkey.

Like almost everything in life, there’s more than meets the eye when it comes to having a monkey for a pet.

Pirates of the Caribbean, Ross from Friends, and Jenna from 30 Rock all lure unsuspecting viewers to believe that monkeys are adorable real-life doll substitutes, perfect for hugging and dressing in sailor suits and mini hats.

I can tell you from personal experience, monkeys make terrible house pets despite their being seen as a luxurious, exotic pet in many places including the United States.

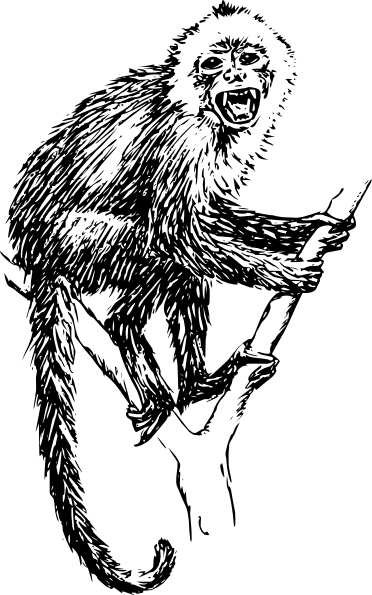

My pet monkey’s name was Jack, which suited his personality characteristics pretty well because he turned out to be a jack-you-know-what.

But they’re trainable, right? Think of all the cute stuff you could teach a monkey to do! Yeah… not so fast.

Being young and bratty, my siblings and I thought it would be great to teach our little monkey to do tricks. Naturally, we taught him the basics: “sit,” “shake,” and “flip-off strangers.”

But monkeys are really smart little buggers. They also learn stuff that you aren’t trying to train them to do — like how to pick locks, sneak out of cages, and leave the house without permission, which leads to my next point.

Monkeys get bored and will try to outsmart others — and will probably succeed at it.

In Ghana, it is common for children to leave for school early in the morning, just about the time the sun comes up, and to not return home until late afternoon, just approaching dusk. All schools are private schools, and students take studies seriously — or learn to because they get beat with a stick, called a “cane” for not learning quickly enough. Somewhere between us leaving for school, receiving our beatings, and returning home, Jack would manage to get himself into trouble too.

Jack learned to pick the lock on his cage, let himself out, and “visit” the neighbor.

He would monkey his way up to the door frame, or so we were told, knock on the door and wait for the neighbor to answer. Once the neighbor opened the door to see who it was, Jack would swing past the neighbor’s head into the house, run about, knocking down items, climbing on the table, generally making a mess, before stealing any fruit in sight, and eventually being chased out of the house with a broom. At first, we thought the neighbor might have been exaggerating, but when she told us he ruined several of her mangos, Jack’s favorite fruit, we had to believe her. We tried changing the locks on his cage, but he somehow managed to keep getting out, and the neighbor was becoming too traumatized to open her door.

Plus, they hold grudges.

After poor Jack would get into trouble with the neighbor, we tried punishing him — but how the heck could we get a monkey to understand what he had done wrong hours later? Oh, he knew! — At least, we came to believe he did. He would act differently on the days he had let himself out for a mid-day stroll when we returned than on the days that he stayed home, without neighborly adventures.

Once we returned home, on days he had gotten into trouble, our Daddy Sammy would inform us that “Jack was a bad little monkey, and the neighbor complained again.” My younger brother, the oldest boy, was in charge of making sure that Jack behaved himself. He scolded Jack, locked his cage again, put a blanket over the cage for warmth at night, and blocked the opening with a chair in an effort to keep him from getting out while we went inside for supper.

The next morning, Jack would be calm until we let him out and gave him breakfast. He would eat as if nothing had occurred, then suddenly attack in a moody monkey fit where it seemed as though he was yelling back, like how a teenager argues with parents, proclaiming eternal hatred for his hurt feelings — shouting loud monkey screeches.

Add “weirdly strong” to moody-monkey tantrums, and we were stuck with quite a problematic pet.

Imagine trying to pull something away from a pet with opposable thumbs.

On occasion, Jack would turn his food bowl into a weapon. He had the temperament of a cat — happy one minute, bitter the next, combined with a fierce vice-grip. Trying to yank anything away from him was like playing tug-of-war with a rope in a pitbull’s mouth who didn’t want to drop the toy.

Only, Jack’s versions of tug-of-war were even less fair. Not only did Jack have opposable thumbs, but he also had a prehensile tail, the ability to hang on our arms while suspended in mid-air, push us away with hind legs, and use both hands and a mouth full of tiny sharp teeth to win the tug-of-war game.

Like a toddler, Jack understood the concept “mine” — grabbing everything he found interesting and taking it away from others — very well. He also fully grasped his power of biting too.

It wasn’t long before Jack became too much of a handful. He outsmarted even our chair tactic for his cage, and we were forced to find Jack a new home because the neighbor was furious and started demanding compensation for the destruction he was causing, and because Jack was clearly unhappy.

As it turns out, Jack probably kept trying to escape because he was out of place and lonely.

In a recent biological anthropology class, I learned that Jack was a Capuchin monkey, and he might have been so grumpy because his home was in South America. Like us at the time, Jack wasn’t accustomed to the African continent.

However, he had found himself victim to powers beyond his control, and transported to another continent, destined to become either an exotic pet or food as a result of both growing trades.

Why do people want exotic pets?

According to Animal Planet, “The practice of importing and exporting wild animals as pets has been happening for decades, and often, entertainment fads determine which wild animals are the pets du jour.”

Demand for exotic pets often increases as a result of celebrity and entertainment culture, and, incredibly, the featured creatures in entertainment don’t even have to be real to bolster demand: “exotic turtles grew in popularity in the 1980s thanks to the popular television show, ‘Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.’ Everything from the smallest reptile to a full-grown tiger can be sold to anyone for the right price.”

Decades later, the exotic pet industry continues to be encouraged by celebrities. Modern celebrities such as Miley Cyrus, Demi Lovato, Zac Efron, Chloe Kardashian, and Justin Bieber have all continued the celebrity trend of posing with exotic animals and various species of monkeys.

However, the article warns that “most owners don’t realize the huge responsibility they are inheriting when they purchase exotic pets, and there’s rarely a happy ending for the animal.” A sad truth, even for celebrities whose financial resources could seemingly support the basic health needs of exotic pets. In the case of Mally, Justin Bieber’s pet Capuchin monkey, German officials had to confiscate the exotic pet while the celebrity-singer was on tour in 2013 due to a lack of proper paperwork. Bieber was given the opportunity to pay the fees, which accumulated to $8,000 US dollars for vaccinations and proper care of the monkey, and resume custody of the pet; however, he did not do so by the deadline and his pet was given a new permanent home at a German zoo.

While many exotic pets face abandonment and improper care by their owners, other exotic animals face dangers of human activity such as deforestation, critical hunting to endangered species levels, and the potential of becoming an exotic meal in the billion-dollar Bush Meat Industry.

Other exotic pet owners have found themselves permanently blind with infected bites that leave lasting scars, or worse, deceased from an animal attack, and some monkeys find themselves unfortunate victims of the Bush Meat Industry or revenge-killed for turning on an owner.

In the end, we were lucky, and so was Jack — with all of his feisty ornery traits — he was still nicer than a lot of other pet monkeys whose owners forgot that monkeys belong in the wild. We didn’t end up with too many scars, and we sent him to a rescue sanctuary where he had acres upon acres to play with others of his kind, where he wouldn’t be cooped up in a cage or inside all day.

Having a pet monkey isn’t as glamorous as it seems because monkeys aren’t meant to be pets.