“Why is He Getting Paid More Than Me?”

It’s 2018 not 1970.

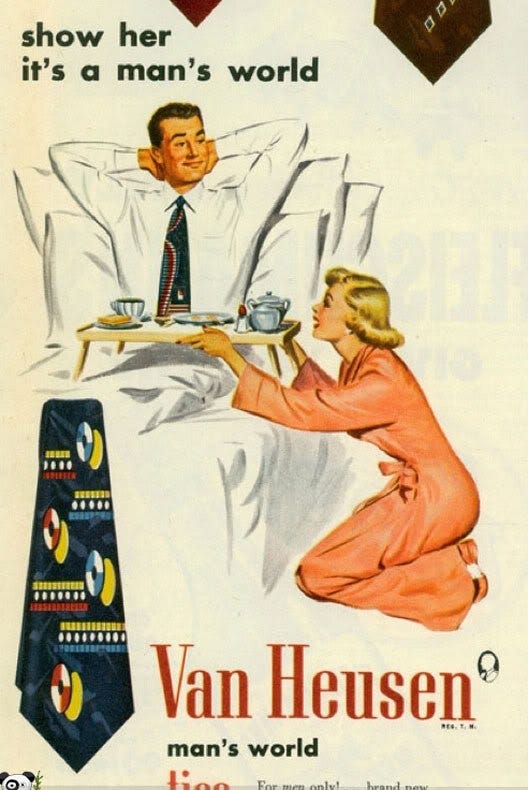

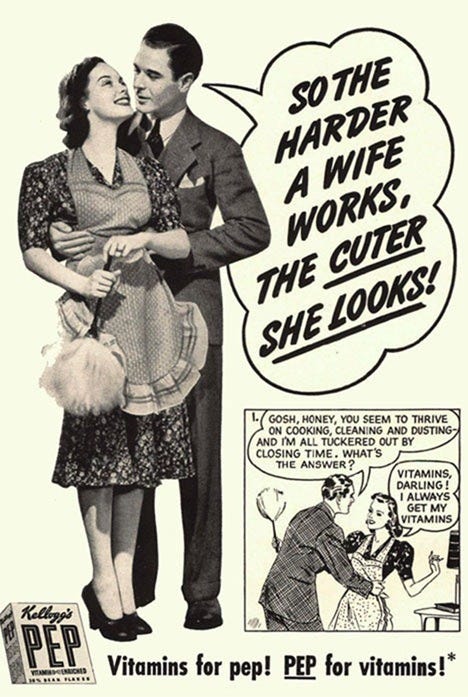

For centuries, women have been known as the primary caretakers of their entire families. American society has created this image of the woman cooking, cleaning the house, and waiting for the kids to get home while her husband is at work.

Back in the day, it really was a man’s world. Via Thought Catalog and Amusing Planet.

Although this may still be true in some households, women have worked their way up the ladder through education and into the workforce since 1970. And with that came an issue called the “gender wage gap.”

The Workplace Gender Equality Agency defines the gender wage gap as, “The national pay gap difference between women’s and men’s average weekly full-time base salary.” This takes into account the different types of occupations in the workforce and how men always seem to get paid more.

In Gaby Hinsliff”s article for The Guardian titled “Gender Equality At Work is a Matter of Respect, Not Just Money,” she replies to the suggestion for women to ask their bosses for higher pay by stating, “What’s so smart about throwing money at whoever shouts loudest? Why don’t managers get better at managing, establishing clear criteria against which objective judgement can be made, so everyone knows where they stand?”

The gender wage gap has been called a myth but now, more than ever, many economists and activists are exploring what a gender wage gap truly means. People believe this is a myth because they claim that women just do not pursue higher paying jobs like men do. However, according to a new census of 2,000 American professional men and women by Ellevest, an online investing platform for women, only 61 percent of men believe that men make more than women for doing the same job. This subject has even been huge on social media when the hashtag #GenderPayGap went viral on Twitter. This trend popularized stats of women’s difference in pay with male colleagues and has even called out big businesses for gender inequality in pay.

The Institute For Women’s Policy Research (IWPR) stated that the “gender wage gap stands alongside the statistic that women working full time and year round in the United States typically make 80 cents for every dollar that men make.” This creates a domino effect; because women do not earn as much as their male colleagues, they get set back and are forced to catch up.

In another article by John Greenwood called “Gender Pension Gap Leaves Women Savings Mountain to Climb,” he states, “The time spent taking care of the children means that women’s pension are on average half that of men’s by age 50 years old.” By this time they would have saved €56,000 ($69,790) in comparison to €112,000 ($139,580) of their male colleagues. Collectively, we must recognize that around the globe, we are not providing a more substantial platform for women in the workforce to deplete this dramatic lifestyle difference.

This 20 percent gap has skeptics raising many questions about the validity of the gender wage gap issue. They pull out of their back pocket the many fluctuating effects of data when challenging the gender wage gap and arguing that it is not real. What counteracts this backlash is the economic studies that have shown age, qualifications, and being a mother keep women’s wages below what men get paid.

However, even when women had the same position, job title, and qualifications, the numbers have shown they are still paid less than men. Discrimination against women who are parental or marital figures puts them on the career back-burner.

Kate Smith, head of pension for the life insurance company Aegon, states, “It’s shocking that 100 years after women secure the vote, we have a gender pay gap across every occupation. The fact that the pay gap filters down to mean women receive lower pension incomes is a double blow. When you factor in women’s ability to save is further interrupted by breaks in their career to raise a family or care for elderly parents, the pension gap reaches epic proportions.”

For one, it is still not common for companies to take into account the effects of women becoming mothers. Many women in their early twenties are valued and starting off in their career by these companies, but when they approach the age where women are most fertile and likely to be married, there is a decline. This decline is directed towards the likelihood of a woman being gone for maternity leave and taking on the role of a wife, which many companies interpret as unreliability; she will not be as reliable as her male colleagues.

Men who become working fathers have a far different role than women do. With pregnancy recovery, women have to adjust to their new bodies post-pregnancy, while men are welcomed back to work as soon as two weeks after their significant other gives birth. Barriers are set for women in the workforce as early as their late 20s and early 30s due to many being the providers of life and mainly taking on the feminine role of care-giving.

This is important because many women are mothers, and companies should do a better job at incorporating this truth in the workforce. This will benefit both the companies and working women of all ages by bringing a sense of creativity, ideas, and perspective. Instead of excluding a whole gender from opportunity because of martial and maternity purposes, we should be thinking of a future filled with possibility for men and women equally.

Due to these facts of life, it is much harder to create an equal environment for women. If American wage equality progresses at our current pace, then IWPR researchers suggest that equal pay will finally be attained- by the year 2059, when most of the women reading this will already be in or approaching retirement. This rate is even slower when it comes to women of color. Studies suggest equal pay for women of color won’t happen until 2248, over 200 years in the making.

Other factors that add to the discrimination against women in the workplace is age. The American Association of University Women (AAUW) has stated that “In 2016, women ages 20–24 were paid 96 percent of what men were paid, decreasing to 78–89 percent from age 25 to age 54. By the time workers reach 55–64 years old, women are paid only 74 percent of what men are paid.”

A reoccurring statement by gender wage gap skeptics is, “Women aren’t getting as much money because they don’t strive for higher paying jobs like men do.” Even if more women work in higher paying positions and male-dominated occupations, they still face a pay gap.

Vivien Labaton said in her article “5 Myths About the Gender Pay Gap,” “Female financial specialists make 66 percent of what their male counterparts make, female doctors earn 71 percent, and female lawyers and judges make 82 percent. That’s all controlling for age, race, hours, and education.” Even though women are more likely to have a bachelor’s degree than men, they are still making less than men do in their fields. There is a major distinction of how far women have come since the past few centuries, but statistics like these should make us more aware of the pervasiveness of the gender wage gap.

Fortunately, there are many women and men who do not ignore the differences in pay and discrimination. There are solutions we can enact among ourselves, companies, and policy makers. As individuals, we can encourage women to strategize and negotiate raises for equal pay. The AAUW provides a salary negotiation workshop to help build confidence and empowerment for women to increase their salaries, benefits, and promotions. For companies and good business, it would best benefit them to conduct salary audits to help monitor and address gender-based pay differences.