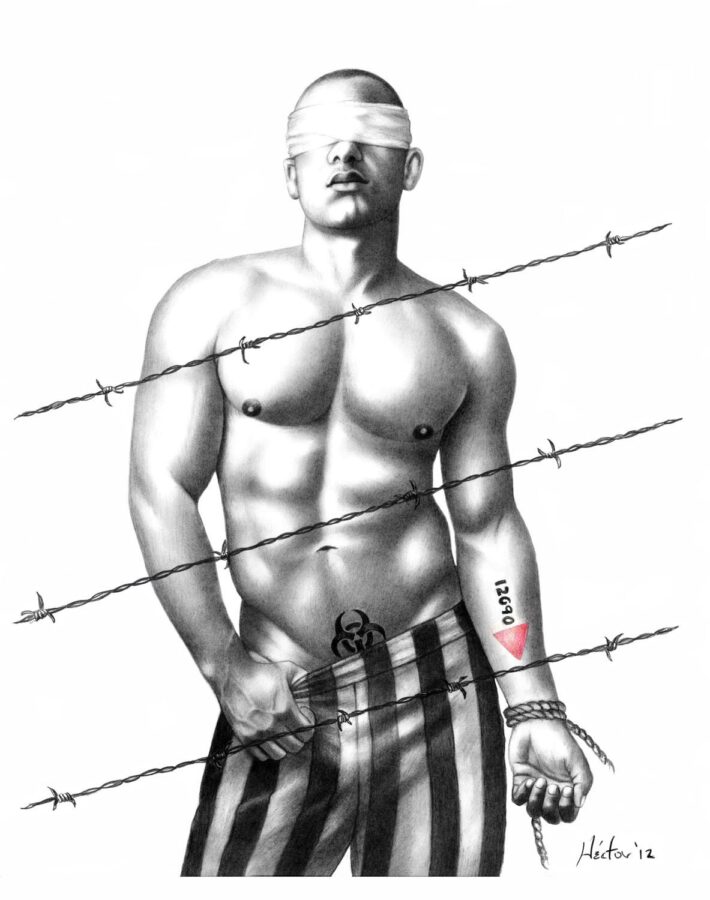

Artist Hector Silva Pushes the Boundaries of Race and Sexuality

Hector Silva explores themes of eroticism and cultural identity through his homoerotic art

“I paint my own reality. The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to, and I paint whatever passes through my head without any other consideration.”

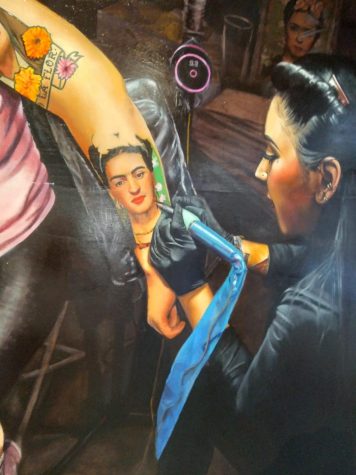

These words spoken by famous revolutionary Mexican artist Frida Kahlo hold a personal truth for many artists who, through the movements of a brush, pencil, pen, or tool, transform a blank canvas into a pure and honest depiction of their dreams, thoughts, emotions, and inspirations. Known for her brand of Surrealism and various artworks that continue to shock and move art lovers 60 years after her death, Kahlo has become a crucial inspiration to many artists —especially those of Mexican descent. One of these artists is Hector Silva.

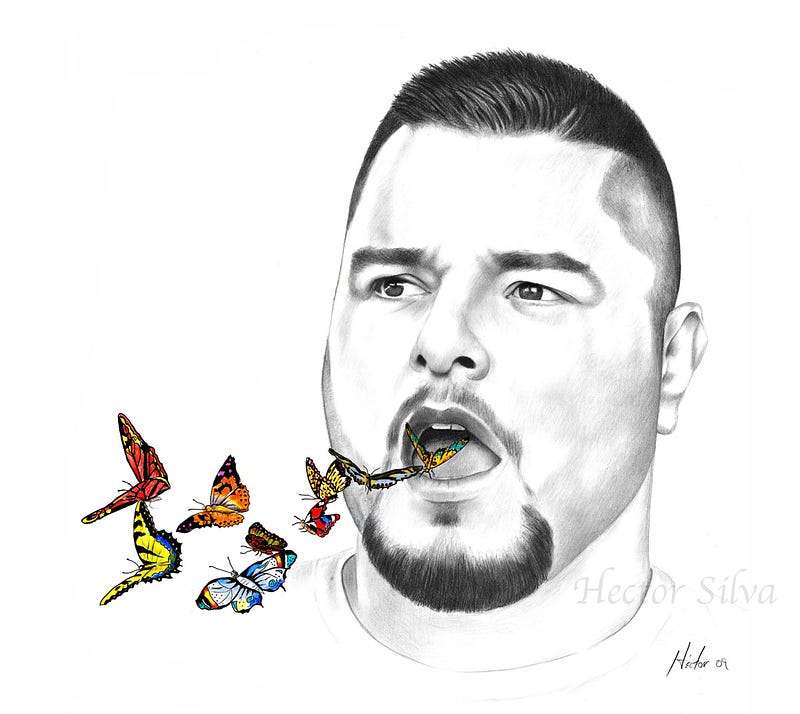

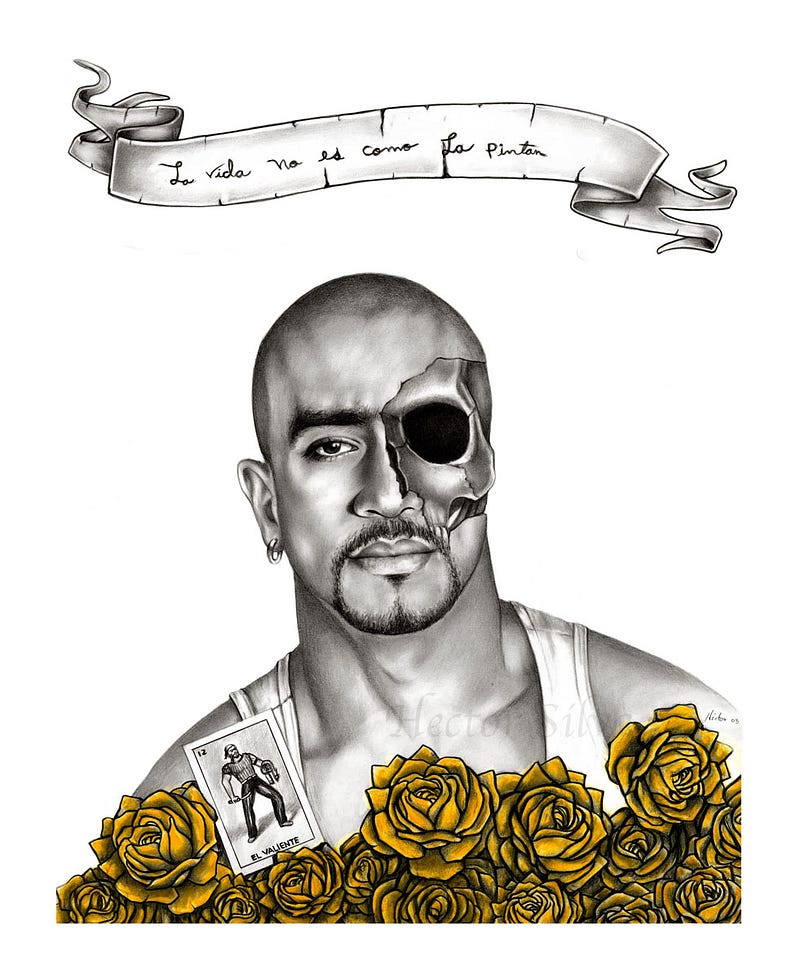

Silva garnered attention for his interpretations of Mexican machismo culture and unapologetically intertwining it with contrasting gay imagery. Through his art, he has defined what is perceived as masculine in the gay community. His use of black and white pencil drawings embellished with bold and bright notes of color became his signature calling card among admirers of his work. His fascination and draw to “homeboy” culture combined with the still-taboo topic of homosexuality —especially in Mexican culture— made Silva a stand out virtuoso who puts two already under acknowledged communities in a new and positive spotlight. But his art is not limited to these subjects. They merely highlight a natural talent he discovered at the age of 25.

Silva’s artistry began in Ocotlan, Mexico. Despite living in a loving but very Catholic home, he found himself itching for a better chance of life where he could find acceptance as a gay man, a virtue that was hardly accepted in the very religious town of Ocotlan at the time. Silva, at the age of 17, left Mexico in his rearview mirror and journeyed to San Diego, Calif. where he was met with the hardship of being on his own and lacking the knowledge of the English language. After living on the streets at 18, Silva found his way to San Diego’s gay community. What Silva did not know was that a visit to a friend, some paper and pens, and bird decor would be the turning point for his future.

“I was looking at a bird on the wall and I started drawing it. It came out really great,” Silva said. “My friend said, ‘Oh, that’s good. I didn’t know you could draw!’ I said, ‘I didn’t know I could draw either!’ He was like, ‘Are you serious?’”

“I didn’t know where it was coming from. So, that was the moment where I said to myself, ‘Wait a minute…what’s going on here?’”

Silva took his friend’s advice and tried his hand at drawing portraits. With his very first creation came a classic portrait of the late legendary comedian and actress Lucille Ball. But little did he know what fate had in store. From his first piece of work, came an opportunity that any artist would clamor to have.

Silva soon found himself at the home of Ball after a print of the portrait fell into the fair hands of the fiery red-haired “I Love Lucy” star. Ball loved it so much that she had to have the original piece of work. This became a defining moment in Silva’s new path in life.

“Lucille Ball told me, ‘You’re a very talented person; don’t ever stop doing this.’ And that day, I decided I wanted to do art. I think that’s when my passion started.”

As word spread about Silva’s encounter with Ball, Silva found himself in the limelight among the gay community. He took this opportunity to assimilate into American culture to gain acceptance and become successful in his career as an artist. Using Hollywood stars, especially those who were considered gay icons such as Barbara Streisand and Judy Garland, and typical gay imagery as the main focus of his drawings, Silva appealed to the white gay male clientele that saturated the gay community at the time.

Even though this brought Silva a sense of acceptance, knowledge of the art business and a steady paycheck, he found himself experiencing a sense of identity loss in a culture that was not his own. It was not until he met his partner of 18 years, Napolean Lustre, who was involved in the culture and art scene, that he found his path back to his heritage.

“What was I doing drawing movies stars?” Silva asked himself. “It had no meaning to me. But I guess it was important I did that because it led to other things. The best thing is that I went back to my culture and got on the right track. And without that, I would have been on the wrong track.”

Using inspiration from current events, whether political, war, immigration, love, or culture, Silva became prominent in the gay community. His work demonstrates a versatility that ranges from beautiful portraits of men and women to an uncensored look into a side of hispanic culture that is still suppressed.

But this was not enough for acceptance in the Los Angeles Chicano art world. There was a looming fear of embracing his Mexican perception of gay imagery, especially pieces that were homoerotic and controversial. Despite his struggle to be accepted, his showcase of a different side of Mexican culture and machismo became the fundamental key to his success.

2009, Hector Silva

“That image of the homeboy, to me, is very homoerotic. It worked because it’s very popular; a lot of women love that art, also, a lot of men too. So, I think it was just a personal taste. That’s what I’m attracted to and that’s what I wanted to do. It seems like no one else was doing it, so that’s why I think it became very popular.” — Hector Silva

Silva’s ability to open a window to a different and unspoken side of Los Angeles’ seemingly tough and macho urban homeboy culture, and giving the viewer an opportunity to ‘stare’ at the subject without repercussion, is what Jacob Prieto, a long time fan and acquaintance, admires most about Silva and his work.

“I think it’s great that we have somebody like Hector Silva depicting things like this,” Prieto said. “He’s giving us an open eye to urban Los Angeles homosexuality. A lot of mass media generalizes the homosexual in a particular way. He contributed to the social consciousness of urban L.A. areas.”

Silva’s approach to his work also resonates with Juan Rodriguez, owner of L.A.’s KGB Studios and Silva’s friend of over 15 years, who said that Silva is giving a sense of identity and place to the world of Latino gay men and women.

“I love that Hector has taken from his life and applies it onto paper,” Rodriguez said. “I think that he triggers and sort of breaks a taboo that exists with Latinos and with our culture about homosexuality. The reality that Latinos, we all have family members who are gay or have sex changes. It’s real. It brings a realness to his art form.”

With a strong following that backed his reputation, Silva was determined to make an impact without comprising who he was.

“At first, I separated my gay art and my culture art. I didn’t want to offend anybody, but that was a while ago. Eventually, I was like, No, this is who I am. If they like it, then fine; if not, then that’s fine also,” Silva said.

Silva finally persuaded galleries to feature his work where it was met with overwhelming success. These opportunities led his work to be published through universities, galleries, and books, while receiving countless awards for it.

Silva was recently recognized by the Speaker of the California State Assembly for “the commitment and unwavering compassion that [Silva has] dedicated to the people of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender L.G.T.B. community and for [his] valiant efforts in the continuous fight for civil rights and social equality.” Silva was also recently awarded with a fellowship from the City of Los Angeles Cultural Affairs Department for his activism and his work.

“That really made me feel like my work was being recognized,” Silva said. “But more than that, the entire queer Latino community was being recognized.”

Not only is Silva active in the L.G.T.B. rights movement, but also in the issues concerning current events in Mexico, such as the response to the Iguala massacre of the 43 student protesters that disappeared in September 2014, and the recent United States protests against police brutality that were spotlighted with the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. Even though his recent work has not addressed these particular issues as of yet, he said the recent art works of protests that have popped up in response to current issues are part of the reason why art exists in the first place.

“I think protest comes when people feel something is very wrong with society. Art helps people think these things through. Art gives us imagery that can challenge the way things are. Art can also give us alternative possibilities, different ways of imagining the world. Art is very useful in changing the world,” Silva said.

Along with drawing and being in hot demand for his works during Dia de Los Muertos (“Day of the Dead,” his busiest season), Silva recently released “The Homoerotic Art of Hector Silva,” a limited-edition coffee table book which contains a collection of 60 images from his classic homoerotic images spanning across 20 years of his career. It also features an essay written by University of Illinois professor of English and Latino Studies Dr. Richard T. Rodriguez, known for his writings on Latino and Latina culture, and his book “Next of Kin: The Family in Chicano/a Cultural Politics.”

Silva is also planning on a milestone show in May 2015 celebrating both his 33 years as an artist and his birthday.

Despite his fame and recognition, friends like Prieto and Rodriguez know that Silva has not changed and still remains the same person he was when he first discovered his art. To Silva, the message is the most important thing.

“A drawing, a painting…it says a thousand words. Something you can’t even describe just by looking at it. I think art is very important. If no one’s trying to censor you, then you’re probably not doing anything that important.”

Header photo credit: “Nuestras Historias Plegadas”(Our Pleated Histories), Hector Silva, 2012. The pink triangle is the symbol Nazis used to mark gay men before they were tortured and killed in the concentration camps. The biohazard symbol is reference to the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and 90s.

Substance is a publication of the Mt. San Antonio College Journalism Program. The program recently moved its newsroom over to Medium as part of a one-year experiment. Read about it here.